In 2013, The New York Times’ Kim Severson wrote a story under the headline “Nashville’s Latest Big Hit Could Be the City Itself,” deeming us “the nation’s ‘it’ city.” Though Nashvillians didn’t know it at the time, that profile became a sort of line of demarcation: All that came before January 2013 was Old Nashville, and all that has happened since is New Nashville.

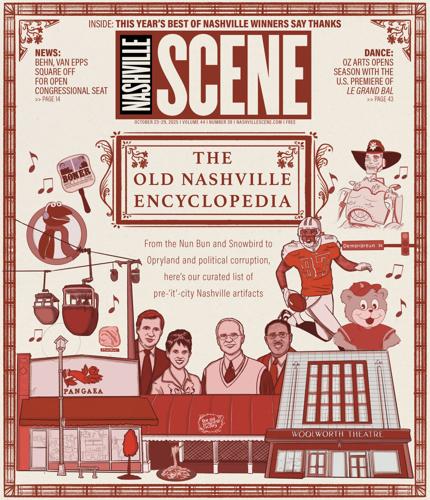

We’ve spilled more than enough ink (including a couple of cover stories) on the Great “It” City Debate. This week’s cover package is not more of that. Instead, we’ve rounded up roughly three dozen entries on classic, pre-“it”-city Nashville artifacts that will strike a chord with long-timers — and bring the New Nashvillians up to speed.

The Old Nashville Encyclopedia is not a comprehensive text. Yes, we could list beloved establishments that have shuttered — like downtown’s Nashville Sporting Goods or Hillsboro Village’s Jackson’s or Brick Church Pike’s Old Timer’s Pit BBQ & Fish. (OK, OK, there is a little bit of that. But covering them all would probably chew up a year’s worth of cover stories.) Instead, what we offer here is a curated selection of political scandals, cringe-inducing moments, colorful characters, forgotten landmarks and erstwhile sports franchises from what we fondly look back on as Nashville’s “small-town” days. No, we’re not reaching all the way back to the days when fur trapper Timothy Demonbreun made a home in a cave near the Cumberland River, or past that to the many centuries when Middle Tennessee was inhabited by a thriving and diverse civilization of Indigenous peoples. For our purposes, we’re (very roughly!) setting the boundaries of the Old Nashville era as 1963 (when Nashville and Davidson County merged to form Metro Nashville) and 2013 (when the aforementioned Times piece ran).

Did we miss something? We’re sure you’ll let us know, and maybe we’ll put it in Volume 2. —D. PATRICK RODGERS, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

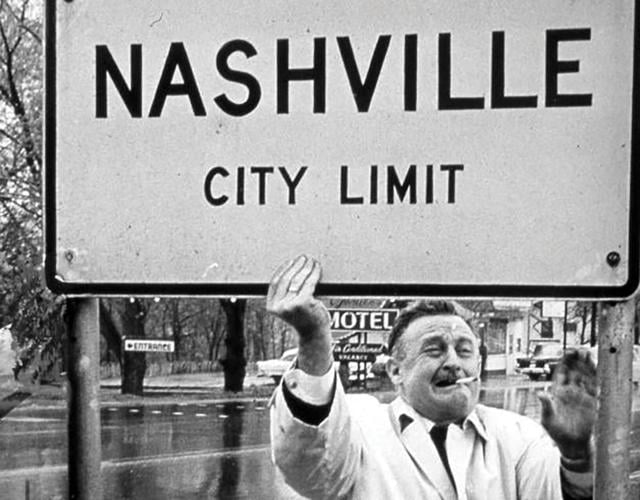

Mayor Beverly Briley

‘40 Jealous Whores’

At 40 members, Nashville’s Metro Council is the third-largest city council in the country — behind New York City’s 51 and Chicago’s 50. And as we speak, the city and the state are engaged in a years-long battle over the Tennessee General Assembly’s attempts to slash the council in half. Over the years, some Nashville mayors have had acrimonious relationships with the body, and perhaps none more so than Beverly Briley — the first mayor to lead Nashville and Davidson County after the consolidation of the city and county governments in 1963. Briley (whose grandson David Briley also served as Nashville’s mayor decades later) famously once referred to the council, which he saw as bloated and bickering, as “40 jealous whores.” Though the phrase is uttered less and less as the years go by, it still lingers in local political circles. D. PATRICK RODGERS

Lower Broad, circa 1970

Adult World

Before Lower Broadway became a redneck Disneyland for bachelorette parties and country singers’ branded bars, it was a grimy haven for the city’s creeps. Adult World was one of the many sexually explicit shops that once lined the strip. When it closed in February 1989, its shuttering marked the end of an era — part of a broader decline that also claimed the Mini Adult Theater on Fourth Avenue North and the Midtown Adult Cinema on Church Street. The change had less to do with morality than with technology: The rise of VCRs and X-rated videotapes made it easy to watch — and rewatch — porn at home, rendering adult shops increasingly obsolete. George Gruhn, who ran Gruhn Guitars next door to Adult World, told Tennessean reporter Renee Elder that the sex-shop business was dying. “If you can rent a porno movie and view it in the privacy of your own home,” he asked, “why would you want to come downtown and spend your money in those places?” LAURA HUTSON HUNTER

Big Tussie Jackson

Nashville music completists may know Carrie Lee “Big Tussie” Jackson as the namesake for one of Lambchop’s early albums, but she was part of Nashville’s fabric long before Kurt Wagner and his band immortalized her on vinyl. (Well actually, Big Tussie was a cassette-only release.) In 1969, the gospel-singing resident of the John Henry Hale Homes — who could allegedly bench press more than 400 pounds — fought off three Metro police officers, and it eventually took six more to bring her into custody. She ran (unsuccessfully) for Metro Council, and according to her attorney — the legendary Avon Williams Jr. — she damn near threw him out of a window. Naturally, Jackson became a professional wrestler on the local circuit. At a time when “girl wrestlers” were largely eye candy, Big Tussie was a certified bruiser (and an excellent mic worker) whose gimmick was that she wanted to fight men and that the promotion couldn’t control her. In a different time, she’d have been a major star. J.R. LIND

Carnival Kia Guy

Chris Bostick was a ubiquitous fixture of local TV ads in the ’90s and early 2000s, urging budget-conscious car buyers at his Carnival Kia dealerships, “Don’t you leave till you see me.” He had all one would expect from a can-I-really-trust-him car dealer: a toothy alabaster smile, golden leather tan, perfectly trimmed and highlighted hair and an overall oeuvre of ostentatious Williamson County new-money wealth. A real Keith Suburban. His fall from grace was swift and bizarre: First arrested for assault, he eventually caught a federal charge for owning unregistered submachine guns. J.R. LIND

Cat Stevens and the Islamic Center of Nashville

The Islamic Center of Nashville, home to the city’s oldest Muslim congregation, occupies a prominent spot in the 12South neighborhood. Its presence there is thanks in part to singer-songwriter Yusuf Islam (best known as Cat Stevens). In the mid-1970s, Nashville’s small Muslim community gathered at what is now the Black Cultural Center at Vanderbilt University. By 1979, the community had grown to around 3,000 members. That same year, with $30,000 in raised funds — including a generous donation from the “Peace Train” songwriter — the group purchased an old house at the corner of 12th Avenue and Sweetbriar to serve as their first mosque. LAURA HUTSON HUNTER

The Church Street ‘Gayborhood’

Gay clubs Tribe Nashville and Play Dance Bar are the remaining strongholds of a mighty “gayborhood” that once stretched down Church Street for blocks. At one time, Suzy Wong’s was its own restaurant (Suzy Wong’s House of Yum) and not just the name of a drag brunch. People ate at gay-friendly restaurant The World’s End (Wednesdays featured “bridge night” happy hour), sang karaoke at Blue Gene’s, danced at New Attitude, hung out at KC’s Club 909 and gathered after hours at Excess. The closure of bookstore Outloud! in 2011 was a blow, but the closing of community center OutCentral in 2018 was a turning point. Canvas moved to East Nashville’s Fatherland Street in 2023, dubbing it the new “gayborhood.” HANNAH HERNER

Dancin’ in the District, RiverStages, Summer Lights, Et Al.

Before Mayor Phil Bredesen had the bright idea to build a stadium and an arena in the middle of town, the city used live music to draw people back into the city. On Thursday nights in the summer, Dancin’ in the District drew crowds to Riverfront Park to see (usually) prominent local acts for a free concert series. How many times can you see Jason & The Scorchers or The Features or The Honeyrods or Fluid Ounces? A lot! RiverStages was a weekend festival that brought in national acts, usually ones that had hit it big on the radio. (Fastball! Semisonic! Everclear!) Summer Lights was a little bit older (both in its own lifespan and its clientele). By the 2010s, Music City would try its own version of SXSW with Next Big Nashville, a club-hopping week of local music with its spiritual roots in those barge-stage nights by the river. J.R. LIND

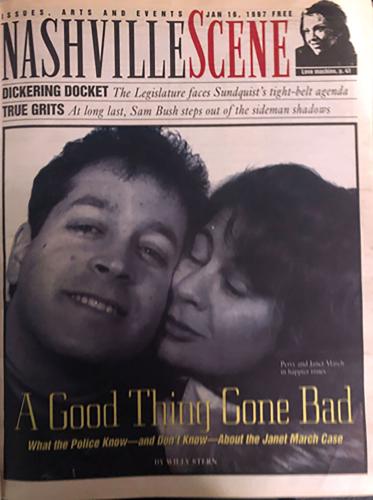

The Disappearance of Janet March

In August 1996, artist, University School of Nashville alum and mother of two Janet Levine March disappeared from her home in Nashville’s affluent Forest Hills neighborhood. As reporter Willy Stern put it in his Jan. 16, 1997, Nashville Scene cover story, “Seldom has an investigation attracted so much attention and inspired so much speculation.” The case — “the most talked-about local investigation since [9-year-old Nashvillian] Marcia Trimble was murdered in 1975,” Stern wrote — made national headlines, with evidence continually mounting against Janet’s husband, attorney Perry March. After legal battles with his in-laws, relocations to Chicago and Mexico, and a secret grand jury indictment, Perry March was convicted of his wife’s murder in 2006, 10 years after Janet’s disappearance — despite no body ever being discovered. After his arrest, Perry March was also found guilty of conspiring, with his father, to kill his in-laws. He’s now serving a 56-year sentence in an East Tennessee prison. D. PATRICK RODGERS

Elliston Place Golden Age

The Gold Rush

More than just one dive, diner or steakhouse, Elliston Place cultivated an aura of niche Nashville nightlife. Jimmy Kelly’s will soon celebrate a century in business; others have since fallen or ascended to second or third lives. The Gold Rush, Calypso Cafe, Rotier’s, Cafe Coco and Elliston Place Soda Shop all were close enough to Vanderbilt and downtown to draw regulars but far enough to create a neighborhood unto their own. Just down West End, Vandyland contributed its own family-friendly dining room. Exit/In and The End (both of which still exist) helped supply a nightly crowd of hungry and thirsty patrons who scattered through the Rock Block before and after shows. The block still gets traffic, but its golden age — when independent businesses flourished over today’s franchised and corporate storefronts — is many locals’ treasured memory. ELI MOTYCKA

Fate Thomas

If post-consolidation Metro had a political boss, it was Fate Thomas. For 18 years as the sheriff, Thomas (an integral organizer of the Hooligans and center of attention at the Last Saturday Breakfasts … more on those later) used his ability to appoint deputy sheriffs to create a clutch of loyalists and — importantly to his fellow politicians — a mighty GOTV regime. Perhaps not shockingly, Thomas eventually met the fate (forgive me) that befalls many Tennessee sheriffs: Indicted on federal charges of misuse of public office, he went to federal prison in the ’90s. J.R. LIND

Funscape

There was a time when Green Hills was fun. For a few golden years in the late 1990s, when boardroom consultants were throwing cash at the emerging kids’ tech market, city birthday parties knew no greater merriment than an open tab at Funscape. As Regal Cinemas prepared for its 1993 IPO, the company expanded its movie theater offerings to include multiroom indoor theme parks. Foam-ball battle rooms, first-gen virtual reality experiences, arcade games and a smoking lounge briefly captured moviegoing families at Regal Green Hills. It was like Chuck E. Cheese done right. To this day, walking down the esplanade toward the box office can still activate Funscape euphoria grooves formed on the brains of many Nashville youth. ELI MOTYCKA

Gathering of the Travellers

In vacant lots and campgrounds along Murfreesboro Road, the green tents would appear, suddenly but predictably, the first weekend of May every…

The American branch of Irish Travellers — a nomadic and clannish ethnic group similar to, but culturally and genetically distinct from, the Roma — see Nashville as a sort of spiritual home. Having first come to town in the late 19th century to take advantage of nearby horse markets in Shelbyville and Murfreesboro and mule centers in Gallatin and Columbia, they formed a bond with the priest at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church. For decades, they’d return in early May to bury their dead, baptize their children, get married and do some courting. With tents and caravans on Murfreesboro Road, the annual pilgrimage was breathlessly reported in the local media. Families still come in the spring but to a far lesser degree. J.R. LIND

Gov. Ray Blanton’s ‘Impeachment, Tennessee-Style’

As contributor Betsy Phillips once beautifully summarized for us: “Ray Blanton was governor of Tennessee from 1975 to 1979, and his time in office was scandal-ridden, to put it mildly. … He gave jobs to all his friends. He did state business with his family’s company. And he sold pardons. That was the big one. You give Blanton enough money and he’ll pardon anyone you want.” Blanton’s exploits at the tail end of his sole term in office were so egregious, in fact, that his own fellow Democrats (yes, Democrats used to actually hold power in this state) teamed up to fast-track Republican successor Lamar Alexander’s inauguration. Lt. Gov. John Wilder later referred to Blanton’s early ouster as “impeachment, Tennessee-style.” Blanton was indicted on mail fraud and extortion charges, spending 22 months in federal prison. The horrific icing on this shitty cake? Decades later, it was determined that Blanton’s administration hired a hitman to kill Samuel Pettyjohn, a cooperating witness in the pardon scandal. (Bonus: In Marie, the 1985 film based on the scandal starring Sissy Spacek, attorney Fred Thompson played himself. Thompson would go on to serve in the United States Senate and also have a successful acting career.) D. PATRICK RODGERS

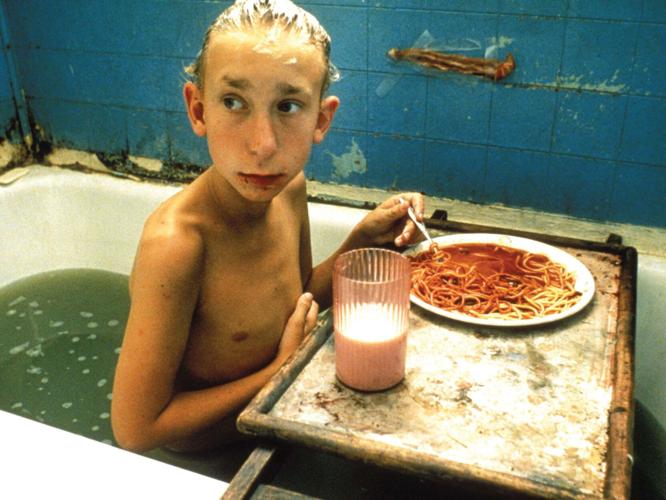

Jacob Reynolds in Gummo

Gummo and ‘Lil’ Bryant Crenshaw

Amid the local film landscape post-Robert Altman’s Nashville, weirdo provocateur Harmony Korine’s 1997 directorial debut Gummo might be the most influential movie to come out of Music City. The ex-Nashvillian’s experimental coming-of-age drama became an underground sensation following its release, its influence appearing everywhere from Donnie Darko to TikTok. Shot in less than a month all over Nashville, Gummo featured several nonprofessional local actors, including “Lil” Bryant Crenshaw. Crenshaw — who could usually be found selling waters at the corner of 12th and Wedgewood near where Smoothie King is now located — made an indelible impression in the film. Sadly, Crenshaw died in 2015 when he was struck by a vehicle on Murfreesboro Road. LOGAN BUTTS

The High Age of Blogging

Blogging was a big deal in the early Aughts, such that WKRN ran Nashville Is Talking, an aggregator helmed by the big-sister energy of Brittney Gilbert. There were meetups and bar crawls and comment wars and flaming and community. That era of blogging included A.C. Kleinheider’s Volunteer Voters (eventually coming under the then-Southcomm umbrella as Post Politics; Kleinheider was a victim of budget cuts and has been the flack for both Ron Ramsey and Randy McNally) and our own columnist Betsy Phillips. Also included: the blog arm of progressive radio show Liberadio(!), hosted by Mary Mancini (who eventually led the Tennessee Democratic Party) and an I.T. guy named Freddie O’Connell. J.R. LIND

Last Saturday Breakfasts and The Loyal Royal Secret Order of Hooligans

These days, the power center of Nashville Democrats might be seen at East Nashville Beer Works, where righteous young progressives gather to be wooed by would-be elected officials. But in the period between Metroization and “it” city, nobody was moving up in the party without doing time at the Last Saturday Breakfasts at John A’s, or schmoozing at the annual Hooligans’ St. Patrick’s Day gathering. Both events still exist, a little grayer but still robust with labor leaders, longtime Metro and state functionaries and what would be called ward heelers if Nashville’s machine didn’t fade away with consolidation and end up wherever the Hopewell box went. The events aren’t so much “gone but not forgotten.” With a rising left in the city, they are increasingly “forgotten but not gone.” J.R. LIND

Lt. Gov. John Wilder

For 36 years, John Wilder served as Tennessee’s lieutenant governor. It was a time of Democratic dominance in the Volunteer State, and the General Assembly was controlled by a faction of rural West Tennessee Democrats (which, at the time, existed). Piloting his plane to Nashville from Fayette County, Wilder became best known for his … unusual relationship with the English language. “The Senate is the Senate,” he’d proclaim without explanation. Once, faced with the problem of senators getting drunk in the chamber by topping off cans of Donald Duck orange juice with vodka, Wilder banned Donald Duck orange juice. “The Senate don’t quack quack no more,” he told the press, the ink-stained wretches no doubt confused why Wilder didn’t just ban vodka instead. J.R. LIND

Traci Peel and Bill Boner on The Phil Donahue Show, 1990

Mayor Bill Boner

Where to begin. After a five-term run representing Tennessee’s 5th Congressional District (largely uneventful, though it did end with an ethics investigation), Democrat and native Nashvillian Bill Boner was elected mayor of Music City in 1987. But Boner hadn’t seen the last of scandal. While married to his third wife, Mayor Boner commenced an affair and subsequent engagement with local singer Traci Peel, who boasted to a Nashville Banner reporter that the couple’s … uh, romantic sessions lasted for seven hours. This detail was brought to national audiences when Peel and Boner appeared on a 1990 episode of The Phil Donahue Show. The episode featured Boner sparring with Bruce Dobie (the Nashville Scene’s founding editor-in-chief) and playing harmonica while Peel sang “Rocky Top.” “There was not a single Nashvillian who did not watch that show,” Dobie recently told me. And it was enough to make Boner the namesake of the Scene’s annual screw-ups issue, the Boner Awards. D. PATRICK RODGERS

Minnesota Fats at The Hermitage Hotel

Nashville has always attracted colorful characters, and few were more vibrant than legendary pool player Minnesota Fats. During his years living at The Hermitage Hotel, Fats (born Rudolf Walter Wanderone) often invited guests and local looky-loos to watch as he performed trick shots on the pool table he kept on the mezzanine. Stories say Fats loved to challenge onlookers to play a friendly game with him for a small wager. After winning the first round, guests were often emboldened enough to play a second round — which they always lost. JANET KURTZ

Minor Leagues

Minor league baseball has been part of the city since, basically, Reconstruction, and the Nashville Sounds returned to baseball’s spiritual home by heading back to Sulphur Dell in 2015. But in the 150 years of minor league baseball, the Sounds and their predecessors have shared the city’s sports scene with other below-the-majors teams. Hockey came with the opening of Municipal Auditorium. The first team — the Dixie Flyers, whose uniform the Predators celebrated with their Winter Classic jerseys in 2022 — was full of talent, as the NHL had only six teams at the time. The South Stars (whose logo featured a hockey player swinging a guitar, à la the Sounds’ Mr. Sound and his baseball-bat six-string), the Knights (their fans’ chants later inspired many that have become part of the Preds fabric) and the Nighthawks (who had a pugilistic rivalry with the Macon Whoopee … seriously) followed. An untold number of hoops teams from various fly-by-night leagues (men’s and women’s) played on the hardwood. The Metros repped soccer for 23 years, the longest-lived team in the United Soccer Leagues. And for a time, Nashville had two minor league teams: The AA Xpress lasted but two seasons, but one of them was the year Michael Jordan played in the bus leagues, and his visits with the Birmingham Barons drew rare sellouts to Greer Stadium. J.R. LIND

The Muse (and Other Bygone Music Venues)

In Hayley Williams’ excoriation of hypocrites “True Believer,” she sings about “The club with all the hardcore shows / Now just a grayscale Domino’s.” If you haven’t lived here long, you may have no idea that she’s referring to crusty punk outpost The Muse, which shuttered in 2012 and became a Domino’s Pizza following what one hopes was a helluva deep cleaning. Indie venues are notoriously difficult to run and aren’t guaranteed to last forever, and we could spend all day listing long-gone spots like Jefferson Street’s Club Baron, Cantrell’s, Lucy’s Record Shop and The Stone Fox. But in this age of corporatized everything, celebrating and supporting what indie venues — both those defunct and ones that persist like Springwater, The 5 Spot and all-ages nonprofit Drkmttr — do for our music communities is crucial. The concern is much more visible in the wake of COVID thanks to national trade groups like National Independent Venue Association and locals like Music Venue Alliance Nashville, which have spearheaded efforts like the Greater Nashville Music Census and the 615 Indie Live festival. STEPHEN TRAGESER

The Nashville Curse

Paramore

While Nashville has had plenty of vital music that isn’t country, it took until the mid-1980s for a local rock band to approach mainstream success. EMI signed the hottest rockers in town at the time, but the marketing suits decided that Jason & The Nashville Scorchers needed to drop “Nashville” from their name, and the group reluctantly went along. Lots of factors were at play in the Scorchers and their contemporaries achieving only modest commercial success. But the idea that the drought was karmic payback for the Scorchers dissing their hometown stuck. Thus was born “The Nashville Curse,” to wit: Rock bands from Nashville were forever doomed to poorly charting singles and meager sales numbers. Who should “break” said curse but Franklin-residing emo-pop-punks Paramore, whose second LP Riot! went gold in 2007 within six months of its release, went platinum in 2008 and was certified triple platinum in 2021. Bands today may or may not achieve Riot! numbers, but many more of them frequently tour the country and the globe. STEPHEN TRAGESER

The North Nashville Music Scene

By the middle of the 20th century, Black Nashvillians turned North Nashville into a cultural and economic hub. A panoply of clubs along and near Jefferson Street made up a thriving entertainment district. They hosted stars and future legends: Among many others, Little Richard had a residency at Club Revillot, Etta James Rocks the House was recorded at the New Era (where a young Jackie Shane cut her teeth in the house band) and Jimi Hendrix and Billy Cox, fresh out of the Army, played the Del Morocco. The city’s decision to build I-40 through the area in the 1960s devastated the community and destroyed decades of progress, and we continue to feel aftershocks. Today a prime resource for learning more is the Jefferson Street Sound Museum: Founder Lorenzo Washington grew up in the area when the district was bustling. STEPHEN TRAGESER

The Nun Bun

This is the story of the Nun Bun, Nashville’s only internationally known pastry. The tale began in 1996 at the Bongo Java coffeehouse on Belmont Boulevard. As recounted on the Bongo Java website, an employee noticed the roll displayed a resemblance to famed humanitarian Mother Teresa. The staff shellacked the pastry to preserve it. Bongo Java owner Bob Bernstein called a tabloid, and the story went worldwide. As it happened, Mother Teresa heard the tale and contacted Bernstein through her lawyer. She didn’t care for one of the phrases being used — “the immaculate confection” — but she was OK with “the Nun Bun.” The bun resided in a place of honor for nine years, until someone broke in and stole it. It was never recovered. DANA KOPP FRANKLIN

Old Second Avenue

More than three years since the Christmas Day bombing, the historic downtown district enters the home stretch of its rebuild

Originally gaining popularity due to its proximity to the Cumberland River, downtown Nashville’s Second Avenue North has seen a couple of forced renovations: from a 1985 fire and the 2020 Christmas Day bombing. (A 1996 historic zoning overlay means the neighborhood’s facades will mostly stay the same from here on out.) The bombing killed off Old Spaghetti Factory and its beloved streetcar (which featured seating), along with The Melting Pot, Rodizio Grill, B.B. King’s, Simply the Best $10 Boutique and others. For natives, Second Avenue North still conjures visions of youth-group haunt Laser Quest and the Market Street Festival. HANNAH HERNER

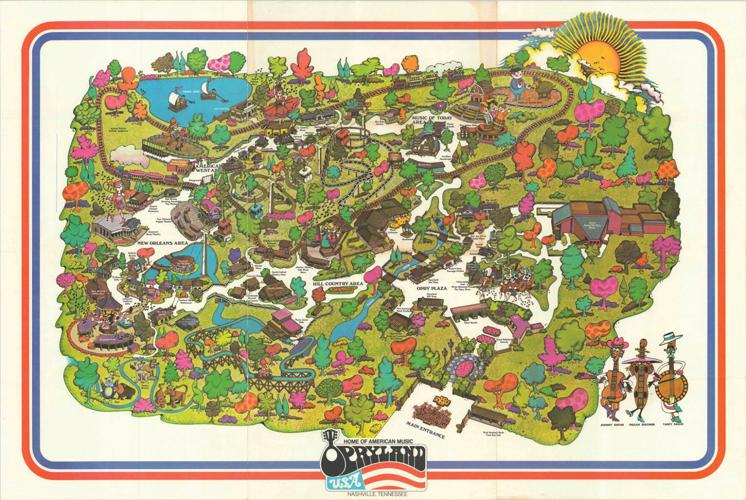

Opryland USA

Nashville was home to an iconic theme park like no other in the country. Then it was shuttered for ‘no compelling reason.’

As we proved with our Dec. 29, 2022, cover story (“Looking Back at the Rushed 1997 Closure of Opryland USA”), we can and have written a great deal about Nashville’s late, lamented country-music-themed amusement park. From May 1972 until December 1997, Opryland brought in millions of visitors with down-home entertainment and some genuinely thrilling rides. Those rides included long-timers like the Grizzly River Rampage (a whitewater-rafting ride used as a qualifying course ahead of the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta — yes really) and the Wabash Cannonball, as well as latter-day additions like The Hangman. And then there was the mind-bending Chaos, whose sister ride Revolution lives on at Antwerp, Belgium’s Bobbejaanland. Despite the park’s long-lasting popularity, affordable fare, status as a de facto babysitter for Nashville-area youths and being featured in Robert Altman’s iconic 1975 film Nashville, Gaylord Entertainment closed Opryland USA to make way for 1.2 million-square-foot shopping mall Opry Mills. The move was later referred to by former Gaylord CEO Bud Wendell as a “dumb, dumb decision.” D. PATRICK RODGERS

Pangea

Pangaea

Pangaea was a Belmont-Hillsboro Village institution that outfitted the bedrooms of a generation of Nashville’s teenagers — at least those with an affinity for celestial designs and stuff with Frida Kahlo on it. Store owner Sandra Shelton opened her shop in 1987 after being inspired by a trip to Honduras and Guatemala, and she kept it stocked with vintage clothing as well as hammered silver jewelry and other home goods. The store was initially housed on Belmont Boulevard in what is now Proper Bagel, but it eventually moved to the corner of Belcourt and 21st in Hillsboro Village. According to a podcast interview with Nashville Public Library from 2023, Shelton says the name Pangaea was a playful reference to intentional community The Farm, which had named its own shop One World. “Wait a minute,” Shelton says about hearing that name. “I took geology — there’s a name for that ‘one world,’ it’s Pangaea!” LAURA HUTSON HUNTER

Quirky Local Pronunciations

Living in Tennessee can leave newcomers tongue-tied. Well-read and well-traveled visitors may be forgiven for mispronouncing the towns of Santa Fe, Lebanon, Milan or Bolivar — none of which sound like you might think. Even seemingly straightforward locale names like Cookeville, Shelbyville and Murfreesboro have their subtle signifiers of who’s from here and who isn’t. God forgive the aspiring politician who slips up on one of those. Here in Nashville, ignore the pronunciation proffered by your GPS when it comes to Buchanan, Lafayette and Demonbreun streets. Duh, it’s duh-MUN-bree-uhn. STEPHEN ELLIOTT

Rabbit Veach

From the 1950s until the early 1980s, there was no career criminal more beloved in Nashville than Clayton “Rabbit” Veach, a serial car thief who became a fixture in the local papers for his sheer unrehabilitated derring-do with the hot wire, his mythical ability to escape from any facility that dared to hold him and his homespun charm and wisdom. He escaped from the psych ward in 1963, and the papers noted it was already his seventh breakout. He escaped from jails in Davidson County, Sumner County and as far away as Oklahoma. Eventually, when he’d be arrested, he’d have to await his appearances at the state penitentiary because no county jail could hold him. His last arrest and conviction, in 1987, was the 58th (that we know of). He spent the last 29 years of his life out of trouble and died in 2016. J.R. LIND

Russell Brothers

When authorities found an abandoned plane, landing gear not deployed, in the grass at the defunct Cornelia Fort Airpark in East Nashville in April 2012, there really wasn’t any question who the plane belonged to — local character Russell Brothers. The septuagenarian was notorious in town for his long history of going to prison for international drug smuggling (which he attributed to a midlife crisis), working at Cornelia Fort Airpark back when it was a working airport, and being nonchalant about the truth. For instance, after this incident, he told police he had nothing to hide. They went to his house and found a bunch of guns, which he — a convicted felon — was not supposed to have. If Brothers hadn’t been up to no good, it’s hard to understand why he appeared to have deliberately avoided drawing any attention to the emergency landing and then snuck away in the middle of the night, leaving the plane behind. But if he was still, ahem, suffering from a midlife crisis, police found no evidence of it. He went to prison on the gun charges and spent his remaining years as a local legend. BETSY PHILLIPS

Shoney Bear

After 30 years affiliated with Big Boy and its ur-Funko Pop mascot, Nashville-based Shoney’s launched its own lovable ursine mascot in 1977. Shoney Bear and his forest friends featured on the kids menu and activity books, keeping young’uns occupied between trips to the fruit-salad-and-soup bar and while waiting for hot fudge cakes to come from the chill box. Soon enough, huggable stuffy Shoney Bears were available for purchase, and ultimately a life-size, full-on man-in-a-costume became part of Nashville’s civic life. Quite literally. For a brief but glorious period of time in the early Aughts and 2010s, nary a major Metro event could pass without someone snapping a shot of Shoney Bear tossing his furry arms across the shoulders of Nashville’s powers-that-be. J.R. LIND

Slick Lawson and Whitland Avenue

When beloved member of the Nashville community Slick Lawson died in 2002, the Scene honored the famed photographer, hot air balloonist, motorcyclist and prankster. Lawson, who created the Whitland Avenue Fourth of July parade, loved keeping his neighbors guessing. One of his best pranks happened while he vacationed in Alaska. While gone, someone planted a sign in Lawson’s front yard that read: “Future Home of Whitland Condominiums. 10 Story Ultra-Modern Highrise. Construction Financing by First Nashville Mortgage Investors.” The quiet neighborhood erupted in consternation, letters to the paper and calls to the mayor’s office in protest. The next week, a sticker was added to the sign “Only 4 Left.” Lawson never claimed credit, but the joke still earns laughs on Whitland Avenue today. JANET KURTZ

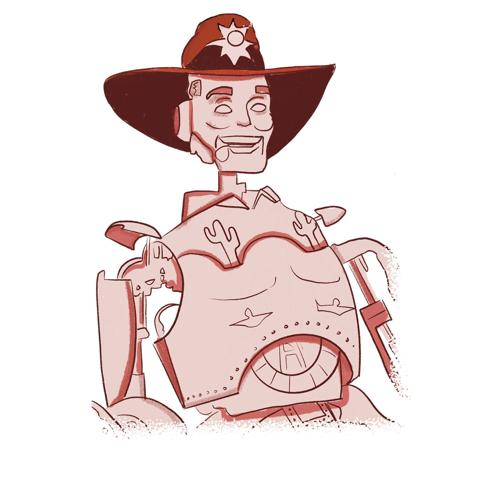

‘Techs’ the Robot Cowboy

You’re 7 years old and you’re at 100 Oaks Mall with your mom, trying to convince her that you really need a new LEGO set. Suddenly, a drawl booms at you from the food court: “Howdy pardner! Wanna sing with me?” The voice emanates from a golden being with a 10-gallon hat and saguaros stenciled on his pecs. You’ve been spotted by Techs, the Robot Cowboy, and there’s no escape. Techs was a sophisticated animatronic puppet run by a live operator who did crowd work from a hidden control room. He was nightmare fuel to area elementary schoolers in the 1990s and early 2000s, though he’s remembered fondly today, as in country duo Westwood Avenue’s wistful ballad “Robot Cowboy.” Techs hasn’t been seen in years, but the company that built him is called Advanced Animations and is still in business. STEPHEN TRAGESER

The Tennessee Titans’ Super Bowl Run

During the 1999-2000 NFL season — the inaugural campaign for the Tennessee Titans, who’d spent the two previous seasons as the Tennessee Oilers — I was a sports-obsessed first-grader. That was a prime age for introduction to sports-fandom heartbreak. Following back-to-back 8-8 seasons, the Titans went 13-3, setting up a playoff run for the ages. Tennessee’s postseason was bookended by two of the most iconic plays in NFL history. The Titans won their opening-round matchup against the Buffalo Bills thanks to the exhilarating “Music City Miracle” — a last-second kickoff return that must be seen to be believed — and fell one agonizing yard short of forcing overtime in the most dramatic Super Bowl ending of the 21st century. I’m not ashamed to admit that I, then 6 years old, cried. The Titans haven’t been back to the Super Bowl since. LOGAN BUTTS

Tennessee Tower Window Messages

Formerly the city’s tallest building at 452 feet and 31 floors, downtown Nashville’s Tennessee Tower was built in 1970 as the the corporate headquarters of the National Life and Accident Insurance Company. For more than two decades, the large, blocky tower wrapped in white travertine limestone would display seasonally appropriate messages at night, spelled out by its alternately lit and darkened windows. These included “Noel,” “Peace on Earth,” “Go Vandy” and — my personal favorite — “Boo,” that last one complete with a rudimentary jack-o’-lantern that looked like something created by an old dot-matrix printer. The tower was purchased by the state in 1994 and renamed the William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower, with the practice terminated due to the expense of leaving all those lights on overnight. There have been municipal efforts to bring back the tower’s window messages over the years, with at least one window slogan (“Peace”) popping up back in 2007. But now the practice remains a memory, a relic of a simpler time in a simpler town. D. PATRICK RODGERS

Woolworth’s

The Woolworth’s department store on downtown Nashville’s Fifth Avenue became an important civil rights site in 1960, when Black students were arrested for sitting at the whites-only lunch counter in protest of segregation. Among the group was John Lewis, a Fisk University student who would later represent Georgia’s 5th Congressional District and see the avenue named for him. The site operated as a lunch counter from the 1930s through the ’90s, and again after a restoration from 2018 until 2020. (It was a Dollar General in the interim.) In 2022, Woolworth Theatre began hosting a residency at the site: Shiners, a raunchy Vegas-inspired “cirque and adult comedy” show. HANNAH HERNER

WSMV’s Classic Era

All the local TV affiliates have things worthy of celebration (Forrest Sanders’ unique feature stories for NewsChannel 5) and ire (basically Fox 17’s entire social media presence). But with all due respect, no channel will top WSMV’s run of dominance. The Nielsen stats may not back this up, but culturally, it felt like WSMV dominated all local news conversations for about three decades thanks to iconic figures like current Nashville Banner executive producer Demetria Kalodimos (wardrobe provided by The French Shoppe), late beloved weatherman Bill Hall, late nationally known anchor Dan Miller and recently retired sports director Rudy Kalis. In 2017, WSMV made the horrendous decisions to let go of both Kalodimos and Snowbird — the latter being the station’s longtime school-closure-signifying mascot. Even though Snowbird has since popped back up on WSMV, the departure of the penguin and the beloved anchor marked the end of an era. LOGAN BUTTS