Tootsie Bess, the original owner of Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge on Lower Broadway, wouldn’t let Robert Altman film in her establishment. At least that’s how the story goes.

In the summer of 1974, Altman’s gigantic cast and crew of West Coast outsiders descended upon Nashville to shoot the acclaimed filmmaker’s epic country music dramedy Nashville. Although Nashville is now considered one of the greatest American films ever made, locals at the time weren’t too fond of its depiction of the local music industry. They also weren’t used to a major film production setting up shop in their backyard. Prior to Altman’s masterpiece, which was released 50 years ago this week, feature films shot in Nashville were strictly the domain of Ron Ormond and his family’s litany of Christian-horror exploitation films.

Looking back at the chaotic local premiere of Robert Altman's 'Nashville' in 1975

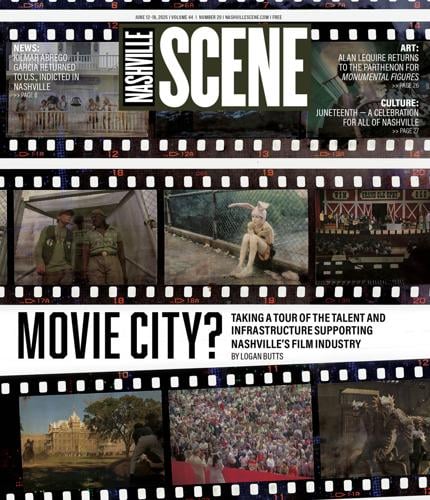

But the past half-century has seen more high-profile films shot in Middle Tennessee than you might think. Since Nashville’s production bopped around town during the American New Wave era, Music City has shown up fairly consistently on the big screen. Portions of Oscar-winning country biopics Coal Miner’s Daughter and Walk the Line shot in the area, and even the Wachowski siblings’ sci-fi-kung-fu-stoner-philosophy game-changer The Matrix — shot almost entirely in Sydney, Australia — features the Nashville skyline. In the background of the mind-bending opening sequence, you can glimpse the Batman Building standing tall as Carrie-Anne Moss’ Trinity leaps across rooftops.

But The Matrix didn’t actually film in town — the local cityscape was green-screened into that iconic opening scene. Unless a movie is specifically about the country music industry (2010’s Country Strong), is independently made by a local (1997’s Harmony Korine feature Gummo) or is seeking a specific shooting location (like the oft-used former Tennessee State Prison featured in 1999’s The Green Mile and 2001’s The Last Castle or the Parthenon in the Greek mythology-centric Percy Jackson series), feature-length films aren’t frequently shot in Nashville.

Unlike second-tier North American film production cities like New Orleans and Vancouver — much less first-call filming destinations such as New York, Los Angeles and, more and more lately, Atlanta — feature film production is far from consistent in the area. Thanks to Nashville’s long entanglement with the entertainment industry, the infrastructure and talent to become a more consistent filming location are here. Music videos, television shows, commercials, award shows, workplace training videos and more are shot here nearly every day. The films haven’t always followed.

But that’s starting to change.

Filming for the Nicole Kidman-starring psychological drama Holland, directed by relative newcomer Mimi Cave, took place in Nashville and Clarksville in 2023. After sitting in development hell for nearly a year, the film was finally released at SXSW and on Amazon Prime Video in March. Though Holland wound up a straight-to-streaming offer, it’s an important milestone in Nashville’s journey to land more movie productions. The film has absolutely nothing to do with the country music industry, it’s not set in Tennessee, and it wasn’t made by a local filmmaker. It’s an expensive-looking studio movie that was shot right here in town simply because Kidman advocated for the production to be close to home.

While another Nashville A-lister, homegrown Harpeth Hall alum Reese Witherspoon — one of the Oscar-winning stars of the partially Nashville-shot and -set Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line — moves further from making movies, Kidman has entrenched herself further in the business. Nashville’s favorite Australian (sorry, Keith) continues to crank out challenging and interesting work with exciting filmmakers. If Music City is going to make the leap to a higher tier, Kidman will be helping lead the charge.

Kidman recently concluded local filming on Scarpetta, an Amazon-produced TV show based on Patricia Cornwell’s mystery book series. More high-profile productions like those mean more jobs, but projects of this scale also bring their own set of problems.

In putting this story together, the Scene spoke to roughly a dozen people working in and around Nashville’s production industry — almost all behind-the-scenes (or “below-the-line,” in industry parlance) crew members — to find out what it’s like to work on film sets in town and how the local industry can grow moving forward.

Any dive into the growth of the local production scene has to include Nashville. No, not Altman’s version — Callie Khouri’s. The Oscar-winning screenwriter’s TV series chronicling the lives of fictitious country musicians lasted six seasons — four of which aired on ABC — and 124 episodes. Having a successful network TV drama film in town was a major boon to the city economically. Crucially, it also helped boost the local film production industry — an industry that, not unlike our music scene, is heavily composed of freelancers and contractors — by supplying steady, yearslong gigs for Nashville-based crew.

“It’s always been feast-or-famine here,” says Eddie Nichols, a longtime on-set carpenter and scenic artist.

Like most production industry workers in the area, Nichols got his start on music videos and commercials before moving on to feature film work. Studio-backed feature film gigs can be more creatively fulfilling than working on something like a reality TV show (many have filmed in Nashville during the past few decades) and can pay more than independent film productions. But they pop up less consistently, which is why a network TV gig can be instrumental for a craftsperson to stay afloat financially in between film projects.

“You may have four or five years before another big production comes through, or another production would come through in Knoxville or Memphis, which is still considered our jurisdiction,” continues Nichols, who is a longtime active member of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees’ Nashville branch, Local 492. IATSE is a union that encompasses a wide range of technicians and craftspeople in the film and television industries.

“But when Nashville the TV show hit, that was when we saw our biggest influx of people, and that’s when our union grew quite a bit,” he says. “And then, as Nashville ended, things started slowing down. People have moved off to Atlanta. Some have stayed. Some have just gotten out of the business entirely.”

It doesn’t help that our Marvel-backed bigger brother to the south, Atlanta, has been siphoning off local workers since Disney’s flagship franchise set up camp in the area a decade ago. But like many of the people we talked to, Nichols hopes the upcoming expansion of Ryan Murphy’s 9-1-1 franchise 9-1-1: Nashville — which begins filming this month — could bring some of those craftspeople back in a more permanent capacity, providing a boost to the local industry similar to the one Khouri’s Nashville gave.

Vū Studios’ recently opened Nashville location is home to an impressive new piece of tech

Nashville has seen a recent influx of innovative sound stages and production studios — facilities like the state-of-the-art Vū Studios in West Nashville, Skyway Studios’ 16-acre gated campus on Dickerson Pike and the sprawling Worldwide Stages at the former Saturn headquarters in Spring Hill. Thanks to those developments, paired with the return of network TV and a series of high-profile productions from Kidman and company, Nashville’s film landscape seems to be rising from the ebb caused by a downturn in the formerly multimillion-dollar music video business and a lack of feature film productions. Plus, there are always live events, commercials, music industry gigs and, increasingly, social-media-related production jobs in the area — jobs that production craftspeople can take to string together a living. Even so, some industry workers resort to side gigs when top-level, higher-paying film jobs don’t turn up.

Vū Studios

“There’s such good, strong, incredibly talented crew here, and it breaks my heart that people are getting out of it,” locally based assistant and second unit director Emily Neumann tells the Scene.

“My friend is a very talented camera operator,” says Neumann. “He’s driving for Lyft because he’s like, ‘I have to pay rent.’ I have a side job. … It’s part of the freelance life, having a side hustle, but when you know there’s potential and there’s shows coming in, and you’re seeing your friends get passed up or not even be considered time and time again, it’s so frustrating.”

The Tennessee Film, Entertainment and Music Commission’s incentive program, which launched in 2006 and has seen multiple restructurings in the nearly 20 years since, is supposed to help fill in these gaps by drawing in more productions. But some of the industry workers who spoke to the Scene expressed frustration with a lack of transparency or results.

“I think we just have to do something to change [the consistency], because at some point, there are people that will grow out of this town,” locally based cinematographer Diego Cacho tells the Scene by phone from the Cannes Film Festival. “They’ll say, ‘My career has hit a ceiling — I need to go find that work somewhere else,’ whether that is Atlanta or New York or L.A.”

Tennessee is a right-to-work state — that is, a state that doesn’t require workers to join a union or pay union dues even when benefiting from their advocacy. Because craftspeople don’t have to join a union to work on a set, unions have less influence when it comes to advocating for workers’ rights, including insisting that movies filmed in town are made up of mostly local crews.

“If you just take a second and talk to the locals and look at their résumés, there’s so much talent here,” Neumann says. “Between a lack of incentives — and I feel like maybe a lack of the Tennessee Film Commission supporting in the right way — there’s a lot of missed opportunities here for longer-form projects, and it’s hurting the crew here.”

The Tennessee Film, Entertainment and Music Commission handles a variety of duties for the entertainment industry across the entire state, including administering state film incentive and grant and tax-credit programs; managing the state’s workforce directory, production location database and filming permits; and acting as a liaison between the state’s production workforce and the local government.

“Since the incentive was created, our economic impact is about $1.2 billion in total impact for the community here — $833 million of that goes directly to new incomes for Tennesseans,” commission executive director Bob Raines tells the Scene.

“It’s also created about 13,000 jobs within the sector. … Our primary focus with this program is that we want to continue to invest in film, television and music that is Tennessean, and to help either develop intellectual property here in the state of Tennessee or implement that IP.”

Figures from the commission’s forthcoming economic data report state that, in 2024, the state’s motion picture and video production sector generated $728 million in economic impact, which was an increase of 45 percent over the past five years.

“People focus on the incentive,” Raines says. “But the truth is that, when I talk with people, they want to talk about our workforce and production community here in the state. … I want the public to know that our workforce is one of the primary things driving success.”

Nashville doesn’t have a high-profile advocate of director Richard Linklater’s status like Austin, Texas, does — which is to say, a notable filmmaker who is committed to filming in town. Several filmmakers have cut their teeth while in Nashville over the years, including aforementioned experimental provocateur Korine and indie success story Kogonada, but few stay. Neither Korine nor Kogonada still lives in Nashville.

“A lot of people have learned here, and gotten better, and then moved away,” Max Butler, a locally based producer, tells the Scene. Butler is the Zelig of the Nashville movie industry, and he has stories to tell. He can tell you about kids’-movie king Chris Columbus attending the Percy Jackson wrap party on the rooftop at Rippy’s, having to find an accent partner for Cary Elwes while filming the axed Epix drama Tough Trade, or Michael Rooker showing up to his office while shooting the FX pilot turned TV movie Outlaw Country.

People like Butler and Neumann were able to earn their bona fides on big-budget productions in places like New York and Los Angeles. (Both worked on Martin Scorsese’s Leonardo DiCaprio-starring horror-thriller Shutter Island, for example.) But in the future, the goal is for up-and-comers in the business to be able to earn those résumé-boosters without leaving town. The infrastructure is in place for it, and so is the community.

“I’ve worked in all kinds of places — in Atlanta, L.A., New York — and I’ve had local jobs where people come from out of town, and they all mention how much they love the Nashville crew,” Cacho says. “It’s because we all know each other, and we all take care of each other. … And I think we all want to prove that we can do the same things that they do in L.A. or New York or Atlanta, and even better.”

Matt Scott, a special effects and makeup artist who helped design werewolf masks for the Nicolas Cage vampire movie Renfield, says being on a local film set has a similar creative feel to working in certain pockets of the Nashville music community.

“I’ve landed several projects while working on set,” says Scott, who honed his craft working at haunted houses and on indie horror films. “You’ll pitch ideas back and forth. … You’re coming up with different ideas, and then that production ends, and you’ll get a call from somebody or an email saying, ‘Hey, you remember working on this with me? We’ve got some funding for this, and I wanted to involve you.’

“There’s much more of a collaborative mindset here versus a competitive mindset,” Scott continues. “If we all work together, we can do cooler things.”

For a city where, for decades, the claim to fame in the film and TV industry was country music variety show Hee Haw, the past 50 years have seen a surprisingly diverse assortment of films shot here — more than the city’s production reputation belies.

Ernest Goes to Camp turns 35 this summer. Let’s talk about the people who were there and the continuing love for the man at the center of it.

The Thing Called Love, a country-music-industry-set romantic dramedy, was one of the final films from legendary film critic turned director Peter Bogdanovich. The 1993 film also featured the final performance from River Phoenix prior to his untimely death. South Korean auteur Park Chan-wook’s Alfred Hitchcock homage Stoker, also starring Kidman, was filmed at a sprawling mansion in the Hillwood area. Films like So Yong Kim’s touching Lovesong, the Robin Williams-led Boulevard (one of the revered comedian’s final films) and Chilean filmmaker Alberto Fuguet’s local love letter Música Campesina show that independent productions can thrive here.

Like Witherspoon in James Mangold’s Walk the Line, Sissy Spacek won her lone Oscar while portraying an iconic country music figure in a Nashville-shot film, taking home a Best Actress trophy for her performance as Loretta Lynn in Michael Apted’s Coal Miner’s Daughter. The booming Christian film industry has made Nashville its quasi-hub.

Set build for Ernest Scared Stupid

And of course, there’s the patron saint of Nashville movies, Ernest P. Worrell. If you’re a local, you know the story: What started out as an advertisement for Nashville-based Purity Dairies became a beloved series of slightly off-kilter family films featuring locals in front of and behind the camera. The late director John Cherry and star Jim Varney’s collaborations epitomize the best of what Nashville’s film output can be: eclectic, long-lasting and community-led.

The ingredients are uniquely in place for a more robust local film industry, but Nashville hasn’t quite cooked them all into an effective dish.

“We have such a strong film community and such great people,” Neumann says. “I don’t understand why we’re not doing everything in our power to get more work here.”