It’s a little more than a week before Columbus will officially open in New York and Los Angeles, and a full house awaits a word-of-mouth preview screening at the IFC Center in Manhattan. The usual chatter accompanies the preview videos, which highlight a collection of European David Lynch film posters on display upstairs. But as the lights dim, the room falls so quiet that when a single chair squeaks under someone’s shifting weight, it might as well be a subway train screeching to a halt.

The debut feature by Nashville director Kogonada, which opens Friday at the Belcourt, demands quiet, attentive viewing — but also rewards it. Exquisitely composed frame by exquisitely composed frame, Columbus transports us to a place that is both extraordinary and mundane. And from the opening credits until the beautiful final shot fades to black, the New York audience sits in rapt silence.

The film is named for and set in the real-life city of Columbus, Ind., a somewhat unlikely repository of modernist architecture. The story opens with a scene at the airy, jewel-box-like Miller House, designed by Eero Saarinen and Alexander Girard. It was built in 1957 for J. Irwin Miller, the Cummins executive who, with his wife Xenia Miller, created a foundation to attract and fund modernist architecture in Columbus. The city is home to more than 50 projects by the likes of I.M. Pei, James Stewart Polshek and Harry Weese.

A book translator from Seoul named Jin (John Cho) arrives in Columbus to see about his estranged father, an architecture historian who had come to give a talk but has suddenly fallen gravely ill. A bright, wise-beyond-her-years recent high school graduate named Casey (Haley Lu Richardson) remains in her hometown of Columbus, reshelving books at the library despite her dreams of going away to study architecture. She feels obliged to look after her mother (Michelle Forbes), a recovering drug addict who is beginning to piece together a working life again. After spotting Jin outside the hospital, and again outside his hotel, Casey offers him a smoke and strikes up a conversation.

To say that Casey and Jin are attracted to each other is both true and an oversimplification. We are used to “attraction” in movies meaning only one kind of thing, and to say much more might spoil some of the surprise that their unfolding relationship holds. But architecture — and specifically, the modernist architecture that surrounds them in Columbus — becomes a kind of language through which they get to know and trust each other. Where Jin had come to hate anything connected to his father’s work, Casey had come to love the buildings she grew up around when she began to see them with fresh and grieving eyes.

Sitting outside a bank designed by Deborah Berke, which seems to float above a nondescript strip mall like a glowing, glass-sided spaceship, Casey confides in Jin how difficult it was living through her mother’s darkest times as an addict. She would come look at this building and be comforted, somehow, by its beauty. If this sounds a bit precious, it might be. In another film, it certainly could be. But the scene, like the film as a whole, has a quiet power, and doesn’t operate on wistfulness alone.

There’s the playful way Casey ribs Jin for how he phrases a question. (Your mother, did she do meth?) And there’s Casey’s self-deprecating humor about fangirl-ing over Berke when she got the chance to meet her. (The real Deborah Berke, who also designed the library branch where Casey works, turned up at a recent Columbus screening.) Cho and Richardson both give tremendous, nuanced performances, and throughout Jin and Casey’s ad hoc tour of the city’s modernist landmarks — and by extension their inner lives — they show off a chemistry as believable in its initial awkwardness as it is in its deepening affections.

During the Q&A that follows the IFC Center screening, Kogonada says that when he made Columbus he was wrestling with the question: Does art matter? In the face of everything that threatens us, this inquiry feels particularly fraught. “It can seem frivolous,” he acknowledges, “when there is tragedy in the world, to do something that takes so much attention and time and money.”

Of the director Jacques Demy, whose work has sometimes drawn scorn for its perceived lightness, the late Scene editor Jim Ridley once wrote: “Try convincing ideologues that upholding grace and beauty in times of ugliness is itself a revolutionary act.”

Does art matter? Kogonada has made an utterly convincing argument that it does.

Still from Columbus

Ben Kenigsberg writes in The New York Times that “the existence of a debut as confident and allusive as Columbus is almost as improbable as the existence of Columbus” itself. So then, how about a movie about architecture, set in Indiana, directed by a Korean-American from Nashville?

Sitting at a table at Thai Esane on 12th Avenue South in Nashville, Kogonada sports a T-shirt that pays homage to the French filmmaker Agnès Varda — her surname printed in the interlocking, serpentine font of the heavy metal band Venom. (Ever one for homages, Kogonada’s pseudonymous nom de cinema is itself a nod to Yasujiro Ozu’s screenwriting partner, Kogo Noda.)

“I think I made a peculiar film in some ways, you know?” he says.

“It struck me as unusual in almost every way,” John Cho says later, recalling his first impressions of the script. Speaking to the Scene by phone from an undisclosed filming location, he says, “He was almost capturing things that in most movies take place off screen ... and I was like, ‘Who can direct this?’ The names coming to my mind were auteurs — names like Linklater or Tarantino or somebody.” Cho was unfamiliar with Kogonada, but his interest was piqued.

“Then I went to his website,” Cho says, “and I thought, ‘Maybe we have our man,’ because I was so moved by his work.” He says he found Kogonada’s video essays “breathtaking.” Their careful observations, he says, “revealed an understanding of the emotional power of movies.” And then, Cho says, “I got really excited.”

As much as anything, Cho says, he just wanted to meet Kogonada, and cheer him on. Both say they quickly felt a kinship, not so much because of their shared Korean-American heritage — although their experiences certainly overlap — as because of how they thought about film.

“I just felt like I was meeting a real artist,” Cho notes, and says he was glad to make the connection — whether or not he got the part. “I was at peace with if he didn’t want to use me; I could dig that. I just thought this movie should be made.”

Luckily, it was. And peculiarity hasn’t hurt the buzz around Columbus since it premiered at Sundance in January. If anything, its particular attention to the poetry of negative space has only heightened its profile. The film has drawn admiration from The New Yorker, Variety, IndieWire and The Los Angeles Times, to name a few.

“You never know how people are going to respond,” Kogonada says. “It’s been really humbling, and a little overwhelming.”

It’s also been demanding of his time: Since opening weekend, Kogonada has been on the road almost constantly — he managed to fit in this lunch interview during a two-day break from traveling. Last week, his new video essay, which studies the motif of doors in the films of Robert Bresson, hit the internet via The Criterion Collection. He’s already at work on a new film, which he declines to discuss, except to say that he’s “super excited about it.” Kogonada is the father of two young sons, and the whirlwind schedule has made him ponder the fictional Jin’s feelings of alienation from a workaholic parent.

As Columbus has made its way into the wider world, Kogonada says he’s been struck by the reaction in other ways, too, beyond the critical response. At a screening in Los Angeles, he says, a man approached him afterward.

“He had lost his father recently,” Kogonada explains. “He’s Asian, a son, has all these sort of mixed feelings — and he just broke down.” The outpouring of emotion surprised both men. While making peace with one’s parents is a universal theme, Kogonada says he’s realizing there’s “something acute” about being Asian-American and watching that experience on screen — in part because it is so rarely depicted there.

“That kind of response has been sort of surprising,” Kogonada says, “because it wasn’t something that I was setting out to do, necessarily. But I also was, of course, aware that there hasn’t been much representation.”

We have grown accustomed lately, in Nashville, to a certain kind of “modern” building, a term which here means predominantly sort of rectangular. The architecture in Columbus, home to seven national landmarks, represents something else entirely.

“We knew that the spaces were going to be important,” says Kogonada.

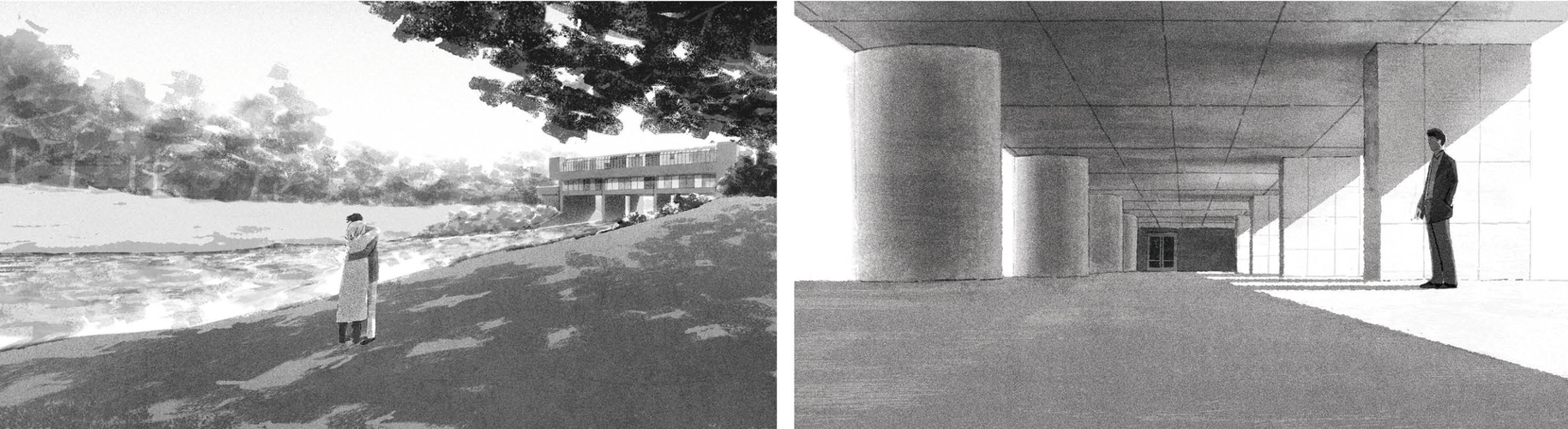

In pre-production, the director had prepared a lookbook for his team that included images from the films of Ozu as well as Michelangelo Antonioni, and Jun Ichikawa’s Tony Takitani. “I also had illustrator Mihoko Takata — I love her work — make some conceptual art,” he says. A week-and-a-half before shooting began, Kogonada traveled to Columbus with director of photography Elisha Christian and producer Ki Jin Kim, the latter of whom has also worked as a cinematographer on films including Spa Night. By then, the team had “a definite idea of what kind of aesthetic I wanted,” Kogonada says. “We kind of looked at every space and really talked about what was possible.”

Columbus Concept Sketches

With just 18 days to shoot, their plan was deceptively simple: “Let’s really just find a few really great compositions,” Kogonada says, “and make it work within those.” To say they made it work would be kind of like saying Days of Heaven has a few nicely lit shots.

The interior of North Christian Church looks like it could be an artful window, or maybe a geometric ceiling fixture of some sort — until we realize that the two ant-sized shapes moving in the corner of the frame are Jin and Casey, and suddenly the scale of it becomes overwhelmingly sublime. The Robert Stewart Bridge, with its high candy-red towers and white suspension cables, looks almost surreal at first. But the workaday traffic moving across the deck helps our eyes make sense of the scene. This kind of juxtaposition of the artful and the commonplace typifies the film’s visual language.

Kogonada says it was important not only to sense the elegance of these modernist works, but also to “feel the everydayness of that space, for it not to feel like just pictures that are passing.” Cho calls the experience of shooting in Columbus “tremendous.”

“I felt like I was interacting with all those spaces,” he says. And just to be clear: To get the full effect, you absolutely must see this movie on a big screen.

Shooting with West Coast talent at a Midwestern location on a modest budget (less than $1 million) meant that being able to assemble a Nashville-based crew was essential. Kogonada says line producer Max A. Butler, who had worked previously with So Yong Kim on the Nashville-shot Lovesong, was “really critical for us to be able to make the film when we made it.”

“I could go down the list and tell you why they were all really important, but they were,” Kogonada says. “Merissa Costanza has been here forever ... and she was right by my side, just a veteran of being a script supervisor, and was so great to have, as a first-time filmmaker.”

Nashvillians might also recognize the music of defunct local rock trio The Ettes, whose song “Eat the Night” provides the soundtrack to a scene that perhaps serves as a kind of visual pun on the old rock-critic idiom “dancing about architecture.” Elsewhere, Ettes bassist Jem Cohen makes a wordless cameo as a bookish store clerk. Providing the soundtrack to the film as a whole is Nashville post-rock duo Hammock, whose spare, sweeping score floats in and out of the incidental sound. (In a sweet coincidence, Hammock’s new album Mysterium drops the same day Columbus opens in Nashville.)

“So much of our conversation with the crew and some of the cast had been this sort of relationship between absence and presence,” Kogonada recalls, “and then I read an interview with Hammock, and they were talking about the relationship between absence and presence in their music — which was a mind-blowing moment — and I thought, ‘They have to be the music for this film.’ ”

But time was short. At this time last year, Columbus was still shooting. The first cut was edited, in Nashville, in just three weeks. Working from notes from the director, the band wrote and recorded their parts on a tight schedule, with the goal of finishing in time for Sundance.

“They were really amazing,” Kogonada says, “and I think a perfect complement.”

For Cho, it came as a bit of a surprise at first, to see a production like this coming out of Nashville — though he says that after giving it some thought, it made sense, given the entertainment infrastructure here.

“I really loved working with everyone,” he says. “It’s a special feeling to achieve something you believe in with people that you like.” Even for a seasoned veteran, it was a memorable time on set.

“I wasn’t sure how far the experience would go, what kind of release we would get, if any,” Cho says, but emphasizes that he would have walked away from Columbus satisfied no matter what happened.

“It was a completely fulfilling experience, the likes of which I hadn’t had in a very long time,” he says. After a pause, he adds, “Maybe I’ve never had. It really reignited my belief in cinema.”

Kogonada and Haley Lu Richardson on set

Kogonada has earned a following for his video essays, which he’s made for Criterion, the British Film Institute and Sight & Sound, among other outlets. Some concern technique (“What Is Neo-Realism?”), visual motifs from a director’s work (“Mirrors of Bergman,” “Ozu: Passageways”) or — at their most intuitive and insightful — a deeper cinematic sensibility (“The World According to Koreeda Hirokazu”). Fans of these essays know they’re not merely visual remixes, but the equivalent of new songs built on samples and infused with Kogonada’s particular aesthetics. It’s no surprise to find traces of them in Columbus.

For instance, one essay focuses on Stanley Kubrick’s use of one-point perspective: A diagram overlays the screen, with clean, straight lines that begin at the corners of the screen and converge at the center. Under it, a lightning-quick montage, comprising dozens of shots from across the director’s career, demonstrates this recurring visual structure in a percussive series of edits.

Kogonada also makes use of this perspective, predominantly in shots of Casey. An alley behind her house stretches toward infinity, or at least toward some distant vanishing point, but she walks along seemingly unaware, smiling at her neighbors. These compositions suggest the vastness of possibility surrounding Casey as she moves through the city that is both the site of her intellectual awakening and the place that keeps her from furthering it. But that’s just one interpretation.

“I’m much more comfortable with open-endedness,” Kogonada says. That’s true even of his essays, which he says some viewers mistakenly take as hard-and-fast lessons. “There’s just something about the process of understanding that I feel much more comfortable with, than coming to some final conclusion and offering it.”

In some ways, making this film has been part of that process.

“When I found Columbus as a place, that meant a lot to me,” he says, “because it did represent so much that had occupied so much of my adult life, which is how do I make sense of being human in a modern world, especially as I find things in the past not tenable for me?”

In Cho’s view, “What our movie shares with his [video essay] pieces is, even though the subject matter was almost academic, it went straight to the heart.”

Kogonada says the autobiographical elements are distributed among the characters, so that none is a perfect stand-in for the director. In discussing the inspirations for the film, he describes “my own struggle as someone who has intellectualized a lot of things that I’ve appreciated.” And so it’s like two sides of his own psyche in conversation when Casey gives Jin a tour guide’s version of the reasons — historical, factual — why the Irwin Union Branch Bank ranks second on her list of favorite buildings. He asks her why she likes it, not why she thinks it’s worth a tour stop.

“I’m also moved by it,” she says at last. “Yes!” he responds. He’s finally broken through.

Kogonada is quick to emphasize that he’s “not trying to create any sort of anti-intellectual response to these things.” Instead, he says, it’s more that part of the experience of art is “about the way things strike us regardless of our reading meaning into it.” So when a camera lingers on, say, two brick structures that seem to float in the air with just a few feet of negative space between them, and remains fixed on them for what — in Hollywood terms — approaches an eternity, it’s OK to let the image wash over us without needing it to mean something exactly.

“There is something about these spaces ... that might have some emotion to them,” he says. “But it wasn’t as if it had a one-to-one correlation with some specific message.”

The cumulative effect, though, is a reverie of sight and sensation. Through hallways and thresholds, in mirrors and through long stretches of illuminated glass, there are glimpses of other lives passing through these spaces and continuing. We get a sense of this as an inhabited place, and of the stories that intersect and flow outward from the main narrative. Columbus is about Jin and Casey’s relationship, but not confined to it. Jin’s father’s protégé Eleanor — a tough, loving performance by Parker Posey — becomes a kind of centering force, even as she works through her own anxious grief.

Then there’s Casey’s friend and sort-of work crush (Rory Culkin). Quoting some marginalia he found scrawled in a library book, he asks, “Are we losing interest in everyday life?” This echoes the question that Kogonada, in one of his film essays, says underlies the work of Koreeda Hirokazu: “Does cinema provide escape from the world, or deeper entrance?”

In the case of Columbus, it is definitely the latter.

Still from Columbus

On Aug. 5, the day after Columbus opened in New York City, about three-and-a-half miles uptown from the IFC Center, the 40th Asian-American International Film Festival convened at the Asia Society. A panel called “The Class of ‘97” celebrated the 20th anniversary of four Asian-American films: Shopping for Fangs (Quentin Lee and Justin Lin), Strawberry Fields (Rea Tajiri), Sunsets (Michael Idemoto and Eric Nakamura) and Yellow (Chris Chan Lee).

At the time of their release, four independent features was a big deal. The Joy Luck Club, while neither universally loved by Asian-Americans nor a runaway hit, was at least a modest success four years prior. And with this group of films, there was a sense that, perhaps, the future held bigger things to come. Some even bandied about the term “the Asian-American New Wave.” Two of those films — Shopping for Fangs and Yellow — featured a promising young Korean-American actor named John Cho. (They were shot during the same four-week window in the summer of 1996, necessitating a delicate scheduling dance between the productions.)

Cho would get his big break two years later in American Pie, and director Justin Lin would get his with The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift. The two would reunite in 2016’s Star Trek Beyond. But the so-called new wave never really amounted to much, and Asian-American film representation has been slow to materialize. For example, no major studio has backed a film with a predominantly Asian-American cast since Joy Luck. Not one.

“Maybe I didn’t realize that casting an Asian-American, or just an Asian male lead in an American film, was such a radical act,” Kogonada says. But financing Columbus was difficult. And it was difficult because time after time, people with money openly said they were not interested in backing a film with an Asian-American male lead.

“It’s pretty ironic,” says Yellow director Chris Chan Lee by phone from Los Angeles. “Because if there’s a bankable Asian-American star, it’s John Cho. Even John is still confronting those kind of headwinds — it’s amazing.” And yet.

“There is this sort of mythology that there’s no interest in Asian males,” Kogonada says, “which just seems so both dehumanizing and ridiculous to me. I mean, people have asked me if I felt hurt by it, but it just seemed so untrue.”

Lee says he’s faced the same opposition in trying to get financial backing. “Every script that I’ve tried to make has had that come up,” he says. “They were like, ‘Why don’t you put white people in it? No one’s ever going to come see this film.’ “

Kogonada is quick to cite his producer Danielle Renfrew Behrens as a champion for diversity, along with Chris Weitz, who sent the script to Cho. “I don’t want to paint the industry with a broad brush,” he says. “There are people in there who want it to happen.”

Still, the barriers are real.

“When you’re Asian-American, we learn from the get-go how to empathize with a culture that’s not our own — we sort of learn to appreciate white culture,” Lee says. “But then you make a film or a piece of art, a lot of people tend to think, ‘This is for this other group, it’s not for me.’ They don’t have that learned ability to place themselves into something else.”

For his part, Cho says, “Jin is a human — not a sketch, not a narrative function — and for that I’m really grateful.” Cinema is populated with characters like this — “thinking through life and having these kind of existential experiences,” as Kogonada puts it — and yet just his presence in Columbus, and the fact that the film got made at all, becomes a kind of statement in itself.

“It reveals whatever the tension is in the industry just by having someone exist in that world,” Kogonada says. “I think that’s enough in some ways.”

But is it? Even with overwhelmingly positive reviews coming out of Sundance, the pattern seemed to be repeating itself when it came time for distribution.

“We did get offers,” Behrens told IndieWire earlier this month, “but they didn’t make sense for us.” Ultimately this led to Columbus becoming an inaugural recipient (along with the documentary Unrest) of the Creative Distribution Fellowship from the Sundance Institute, which provides marketing and distribution help for completed films. The goal here is to help Columbus find its audience, which on paper includes design buffs, independent film aficionados and “architecture nerds,” as Jin would say.

And yet by making a film that shows the John Cho many of us have been waiting at least 20 years to see — flawed and complicated and, by circumstance but not necessity, Korean-American — Kogonada may have inadvertently become part of a new new wave of sorts.

“The character’s racial history is not ignored, but it’s not central to the story either,” Cho says, “and in that way it feels genuine and real to me. And I wish for more films like that.”

Perhaps with Justin Chon’s Gook making waves and Jon M. Chu’s Crazy Rich Asians adaptation in the pipeline, there will be a Class of 2017 to talk about someday. Whatever happens, Columbus stands, in its peculiar and beguiling way, as its own achievement.

As Kogonada puts it, “I just made something that I knew.”

Email editor@nashvillescene.com