The crowd at the Nashville Premiere of Nashville

This excerpt appeared as part of a Scene cover story by Jim Ridley 20 years after the release of Robert Altman's Nashville. See "Look Back in Anger," Nov. 9, 1995.

Even by Nashville standards, the scene outside the Martin 100 Oaks Theater on Aug. 8, 1975, qualified as a spectacle. On a hot, gusty Friday night, more than 4,000 people crowded behind police barricades. Some of them had stood in line for five hours. The Tennessee Twirlers, a platoon of star-spangled majorettes equipped with flags and rifles, stood at attention. Atop a 40-foot flatbed truck festooned with red, white and blue bunting, a band called the Silver Spurs reeled off country tunes. The white-hot beams of searchlights swept the sky.

It could have well been some sort of grandiose political rally. But the elections were over. Just the day before, U.S. Rep. Richard Fulton had won a landslide victory over Earl Hawkins to become the second mayor in Metro Nashville history. And here was Fulton, smiling and waving to the crowd, along with incumbent Mayor Beverly Briley.

The steel arm of a construction crane had lifted a 60-by-80-foot American flag into the sunset. But by 6 p.m. the flag was coming down. The hot August wind was snapping the massive flag like a locker-room towel, and, with the festivities barely under way, a decision was made to rescue the flag and fold it away. The last thing the makers of the movie Nashville wanted was to cap the film's local premiere with an image of Old Glory lying in the dust.

The gala premiere of Nashville was the most eagerly anticipated event of the summer. During the previous year, ever since the production company had finished shooting its local footage, curiosity about the film had reached fever pitch. The previous March, The New Yorker's influential film critic, Pauline Kael, had pronounced a barely finished three-hour cut of Nashville "the funniest epic vision of America ever to reach the screen." Kael's review alone had triggered waves of controversy, mostly from other reviewers, who were angered that they hadn't been invited to the private screening.

By the time the movie had finally opened in New York in June, it had become a cause célèbre. Its studio, Paramount, had confidently booked Nashville into two adjacent screens on the East Side. It filled both theaters daily. In every major national publication, critics and editorial columnists debated the movie's merits; gossips speculated about the lead characters' real-life counterparts, identifying everyone from Loretta Lynn and Tammy Wynette to Roy Acuff and Hank Snow. In its cover story for June 30, 1975, Newsweek proclaimed that Nashville was director Robert Altman's "epic of Opryland" and "everything a work of social art ought to be but seldom is — immensely moving yet terribly funny, chastening yet ultimately exhilarating."

Back in Nashville, however, the locals were getting nervous. According to some critics, among them Robert Mazzocco in The New York Review of Books, the movie portrayed Nashvillians as gullible rubes at best and heartless automatons at worst. Others, including syndicated reviewer Rex Reed, agreed, but declared that Nashvillians deserved what they got. "[The film] floats like navel lint into the vulgar Vegas of country and western music, that plunking, planking citadel of bad taste called Nashville, Tenn.," wrote the former star of Myra Breckinridge.

Even the most positive advance reviews carried an implicit — and sometimes explicit — condescension toward Music City in general and country music in particular. "Country-and-western basically dresses up folk music in rhinestones and spangles, making hay out of Americana," Jay Cocks wrote in Time. Despite an unequivocal rave from The Tennessean's Eugene Wyatt, who declared himself "a Nashvillian who loves his city and wishes it well," word still filtered back that the movie was anti-American, anti-country — and anti-Nashville.

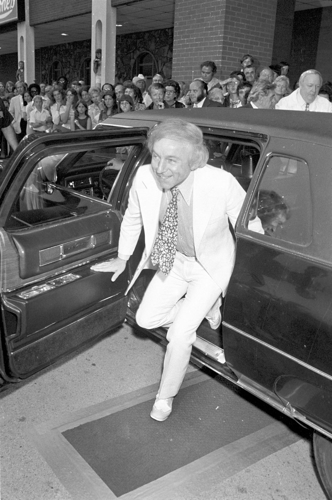

With a mixture of anxiety and dread, musicians, producers, music-industry personnel and civic boosters alike had awaited the film's local premiere. Hardly anybody, though, had any intention of missing it. As the 7:15 p.m. show time neared, long lines of limousines snaked down Powell Drive toward the Martin. While flashbulbs popped and fans applauded, dozens of celebrities and local dignitaries emerged from their vehicles, crossed a red carpet and ducked inside the theater.

The audience, half of whom were invited guests, formed a cross section of the city as broad and colorful as any Altman could have devised. On hand from the music industry were established hitmakers Dottie West, Brenda Lee and Billie Jo Spears; Opry veterans Roy Acuff (who left before the movie started), Minnie Pearl and Del Wood; new country superstar Ronnie Milsap; producer Billy Sherrill; and the great Webb Pierce, whose raw honky-tonk sound was fading in popularity. Sheriff Fate Thomas was there to appoint cast members as honorary deputies. Tennessee first lady Betty Blanton represented the governor. While Altman himself was busy shooting his next film, stars Ronee Blakley, Henry Gibson, Keith Carradine and Dave Peel represented the film's makers.

Outside, while the Rutherford County Square Dancers clogged, the celebrity-studded crowd slowly disappeared into the Martin's auditorium. The few remaining tickets for the performance were sold to eager patrons, who had begun lining up outside the box office shortly after noon. Once the theater's 741 seats were filled, at approximately 7:40 p.m., the lights in the theater dimmed, and the words "A Robert Altman Film" flashed on the screen.

What followed was a visual and aural cacophony, a credit sequence modeled on the commercials used to sell repackages of country hits on late-night TV. As a pitchman hawked the names of the movie's 24 principal actors, their representative "hits" scrolled beside [local illustrator Bill Myers'] painting of the entire cast. In the center of the Panavision screen, one word in bold, tilted type overwhelmed everything else — the word "NASHVILLE." The applause for the title was loud, long and appreciative.

Two hours and 39 minutes later, the crowd that remained outside behind the police barricades saw the audience begin to emerge from the theater. The ensuing madhouse made the front pages of both daily newspapers. It made all three evening news broadcasts and was carried in columns from Atlanta to Italy. Exiting audience members were ambushed by print, TV and radio reporters anxious for comment. Some audience members, among them Buddy Killen, then executive vice president of Tree International, had enjoyed the movie.

"I loved it," Killen told the papers. "I was not offended in any way. It was a great piece of work."

Others were guarded. Dottie West said she liked it OK, although she expressed concern that the movie's only redhead did a strip number. "It was very interesting," Minnie Pearl told the [Nashville] Banner's Bill Hance — and then, with uniquely Southern diplomacy, she concluded, "Sure is good to see you tonight."

The majority of the Music Row insiders, however, were not quite so reserved. "I've seen a lot of movies in my day," Ronnie Milsap told Hance, "and this is one of them." Brenda Lee said that she had "one word" that would describe the movie, and her husband, Ronnie Shacklett, begged her not to say it. "The only way it will be a big movie is for it to play a long time in the North," Lee told Hance. "That's what the people up there think we look like anyway." Producer Buzz Cason commented, "It was so bad, it was different."

The harshest remarks came from Billy Sherrill, who, when asked by a journalist what he thought of the music, retorted, "What music?" Asked what he liked best about the story, Sherrill snapped, "I'll tell you what I liked about the film — when they shot that miserable excuse for a country music singer."

Twenty years have passed since Nashville's premiere, and opinions about the movie remain as divided now as they were in 1975. "I can't tell you how many people whose opinions I respect place it among the top 10 movies of all time," insists Gene Wyatt, who believes now, as he did then, that Altman's film is "one of the landmark efforts of the art." In direct contrast, music executive Charlie Monk, who attended the 1975 premiere, remembers Nashville as "just bad," an insult perpetrated "by people with no knowledge of the blue-collar-folk idiom."

Banner editor Eddie Jones, who in 1975 was executive vice president of the Nashville Chamber of Commerce, sounds a note of moderation. "The civic leadership-type people felt it was not representative of the city," Jones recalls. "Honestly, I don't think anybody paid a hell of a lot of attention. It just kind of tippy-toed into town and tippy-toed out."