Keeping up with ICE is exhausting work. This year, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement grew more aggressive and unpredictable, and as a result more calls and tips flooded into the hotline operated by the volunteers at Music City MigraWatch. After receiving word of ICE activity, volunteers coordinate efforts to verify officers in the area, sharing to followers online whether the sighting was a false alarm or the real thing. And if someone gets to the scene of an arrest quickly enough, the MigraWatch team does their best to ensure the detainee knows their rights.

Immigration has been one of the biggest issues of the year, from the federal to the local level. President Donald Trump’s increased enforcement — highlighted by bloating the ICE budget, ramping up recruitment efforts and setting absurd arrest quotas — has led to certain neighborhoods in cities like Chicago and Los Angeles resembling occupied war zones. Some mayors and governors have stood up to the president on the issue, becoming national targets of conservative outrage. Other politicians have fallen in line, including the overwhelming majority of Tennessee Republicans, who passed bills that encourage police departments to cooperate with ICE and penalize lawmakers who seek to protect undocumented immigrants.

In May, an unprecedented weeklong operation rocked Nashville when the Tennessee Highway Patrol collaborated with ICE to conduct extensive traffic arrests in South Nashville, home to predominantly Latino neighborhoods. Troopers and ICE agents detained 196 people, most of whom had no criminal history. Music City MigraWatch volunteers were on the scene documenting arrests and trying to spread the word about where the operation was taking place.

Immigration roundups terrorize South Nashville and take residents with no criminal history

The turmoil of that operation also led to a surge in Nashvillians enraged and distraught over the action and seeking ways to help. The Tennessean reported that by the end of May, MigraWatch ballooned to 200 volunteers.

Cathy Carrillo established the MigraWatch hotline under her grassroots organization The Mix back in 2018. One year later, Carrillo took part in preventing officers from detaining a Hermitage man who had spent hours sheltering in his van with his son outside their home. Neighbors and other Nashvillians formed a human chain to block agents from the man. (Carrillo details the hectic day in an interview with the NPR-distributed podcast Radio Ambulante.)

“It comes down to people knowing their rights and people knowing that there are other folks out there that care,” Carrillo tells the Scene. “There were about 40 people that were community members, advocates, councilmembers, folks from other nonprofits in that space calling for ICE to leave. And eventually, they did.”

After Trump’s election in November 2024, The Mix — which had rebranded to The ReMix Tennessee — once again set up MigraWatch. After the May operation, MigraWatch and The ReMix were inundated with requests to volunteer or donate and questions about how to help. The growth was exciting, but signaled a time to change.

In June of this year, Music City MigraWatch became an independent organization, and its parent organization again rebranded, to The ReMix Way.

“After the May raid, we knew that it was important, in order for both groups to keep capacity and to be able to grow … to make it two separate spaces,” Carrillo tells the Scene.

The two groups still work closely together: MigraWatch could be considered the response unit (it’s “our 911” says Carrillo), while The ReMix handles mutual aid and community support for immigrant families affected by these operations. And membership overlaps, with many people organizing ReMix fundraisers and fielding MigraWatch tips.

Scroll through MigraWatch’s Instagram page (@musiccitymigrawatch) and you’ll see posts confirming reports, photos of suspected ICE vehicles, graphics warning people about increased state trooper presence at events like soccer games, protest announcements and warnings about misinformation.

@musiccitymigrawatch’s Instagram page

Two volunteers who help manage the hotline are Ashley Warbington, who also volunteers with The ReMix, and Gisselle Huerta, co-founder of advocacy group Hijos de Inmigrantes (Children of Immigrants). The trio spoke to the Scene one day after a suspected ICE arrest was made outside Sip Cafe on Gallatin Pike, followed by a flurry of other reports and rumors.

Sitting inside Tempo on Nolensville Pike — adjacent to Latino community center Casa Azafrán, across from stalwart Vietnamese grocery store InterAsian, and up the road from various enclaves of immigrant communities and businesses — the three admit they’re a little “fried” after the preceding 24 hours.

Rapid-response groups chase reports of detentions, but local and state law enforcement deny involvement

Huerta had been driving around the city all morning, and Warbington had been monitoring ICE’s field office just off Brick Church Pike. Their phones light up often at the table, no doubt receiving more Signal messages about potential sightings. As they speak to the Scene, Huerta and Warbington are also preparing for an upcoming training event, where they’ll be able to teach a new crop of volunteers how to get involved in documenting ICE activity and alerting the community. Training sessions are also now being offered in counties outside of Nashville.

“I’ve been able to see hundreds of people come through MigraWatch,” says Carrillo. The hotline was started by a group of young adults — “kids, truly,” says Carrillo — but has “evolved into something that’s so much more.”

For inspiring Nashvillians to defend their immigrant neighbors, the Scene has chosen as our Nashvillians of the Year Music City MigraWatch, represented here by Cathy Carrillo, Gisselle Huerta and Ashley Warbington.

Cathy Carrillo’s father was deported when she was 14. He was driving her to a track meet when Metro police pulled him over for a broken tail light. Speaking recently to the Nashville Banner’s Demetria Kalodimos, Carrillo said her father didn’t know his attorney had just lost his immigration case and there was a deportation order. He was arrested and taken away immediately.

“What was supposed to be just a ticket for a broken tail light ended up in my dad, who had spent 15 years of his life here in Nashville, being taken away from me,” she tells the Scene, “and me at 14 years [old] being left on the side of the road.”

Gisselle Huerta’s parents were undocumented for years, becoming permanent residents after 25 years living in the States. Her group Hijos de Inmigrantes organized a “Day Without an Immigrant” rally in February, part of a national protest against Trump’s policies and rhetoric. Huerta and her group also worked closely with The ReMix on advocacy at the Tennessee legislature against the state’s slate of anti-immigrant bills. She’d go on to join MigraWatch during the May operation.

Ashley Warbington has also been a presence at the Capitol, testifying during the most recent legislative session against a bill that would make it illegal to “harbor” undocumented immigrants. Warbington was no stranger to activism — she had already advocated for gun control alongside other concerned parents at the Capitol in recent years. Warbington joined MigraWatch in January, after The ReMix held a know-your-rights training at her son’s school. She recognized one of the volunteers, who invited her to join the hotline.

Complaint calls legislation unconstitutional, says it criminalizes broad array of everyday activities

Working the MigraWatch in May was fast-paced, Huerta says, with events happening “back-to-back throughout the whole night.” The days were spent organizing and preparing for the evenings. While ICE activity slowed down after the May operation, Huerta says the agency has gotten “bold” in recent months, showing up at courts, for example.

Verifying ICE activity might start with the MigraWatch hotline receiving a photo. ICE reuses the same vehicles, and the MigraWatch team has photos of the usual fleet of cars and plates. A verifier sent to the scene will take more pictures if the officers are still on site. If an arrest is in progress, Warbington says they try to let the detainee know their rights.

“We let that person know that we are there with them, that they are not alone, and to let them know that they do not have to respond to any questions,” she says. “They have the right to remain silent. And if someone is actively being detained, we do try to get … an emergency contact number so that we can verify a family member.”

Part of the job is flagging misinformation and misunderstandings. Sometimes rumors circulate, and a verifier arrives at the scene to confirm there are no ICE agents around. Sometimes an arrest is happening, but it’s not immigration enforcement — it’s MNPD or another agency. To an extent, false alarms signal how much chaos the looming threat of deportation inserts into daily life.

“They actually create more fear and panic and cause people not to want to interact with law enforcement, not want to report crimes, not want to look for help,” says Carrillo, “and we know that that’s going to lead to an even bigger humanitarian crisis.”

Carrillo points to one example: speculation that a 6-month-old child in La Vergne may have died because the caretaker was afraid to call emergency services due to their immigration status.

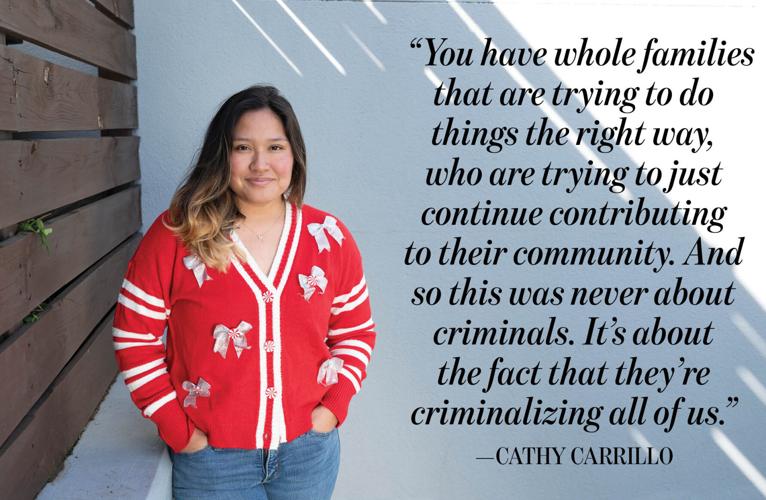

Carrillo also stresses that these ICE raids aren’t targeting criminals, but “working-class people.”

“You have whole families that are trying to do things the right way, who are trying to just continue contributing to their community,” she says. “And so this was never about criminals. It’s about the fact that they’re criminalizing all of us.”

Cathy Carrillo

More than 50 people are gathered in the pews of Glencliff United Methodist Church on a Sunday afternoon — the site for December’s MigraWatch training. The attendees range in age, some looking like college students, others like seniors; the majority appear to be white. Huerta says it’s one of the biggest groups they’ve had this year.

Most of the crowd is here for verifier training, where they’ll learn how to confirm ICE activity and how to act when at the scene of an arrest. Warbington and fellow MigraWatch volunteer Luis Pedraza lead the verifier training, which also includes information on the rights of citizens and noncitizens alike.

In a slideshow presentation, Pedraza and Warbington stress the need to record everything — and they stress the fact that volunteers have the right to do so. An officer may demand verifiers back away, and under Tennessee law they’ll have to maintain a buffer of 25 feet. But even at that distance, Pedraza says, you can capture an event like an ICE agent dragging someone out of their car or smashing a window.

Twelve attendees break off into a smaller room for the inaugural court accompaniment training session called Sombra Segura, or Safety Shadow, led by Gisselle Huerta. The new training is partially inspired by a surge in ICE presence at U.S. courthouses, and Huerta points to cases of traffic tickets leading to arrests at the Wilson County and Robertson County courthouses.

Immigrants face a catch-22 when ICE shows up at court. If they follow through with their appearance, they risk arrest no matter the ruling. If they skip the hearing, they risk a warrant for their arrest.

Court accompaniment isn’t about providing legal advice, but might involve driving someone to court (which could be helpful if they were cited for driving without a license), helping them keep their appointments, going through paperwork and even navigating them through the court building. Huerta recommends getting someone’s alien registration number, or A-number, as soon as possible to track their records.

The role will also call for spotting ICE activity at the courthouse. Courtrooms tend to prohibit recording devices, so Huerta recommends working with a teammate who can monitor outside the building for an ICE presence as well.

Huerta also fields ideas from attendees for the nascent operation, and there’s a lot of discussion about expanding efforts beyond Davidson County. One attendee offers to help out in more rural counties. Another asks if it would help to get more Arabic speakers involved, and Huerta responds with an excited “Yes!” Immigrants in Middle Tennessee aren’t just Spanish speakers, after all. And immigration enforcement isn’t focused only on Nashville.

“Whoever you want to bring, bring them,” Huerta says to the cohort.

It’s been a chaotic year, and Trump still has three more left in his second term. Keeping up with enforcement escalation, mercurial immigration policy changes and Tennessee’s own legislature is grueling work. Carrillo, Huerta and Warbington still need to balance their activism with raising their own kids and navigating their own family lives. Warbington says it can be surreal to sit outside the ICE field office and sign up for something at her son’s school at the same time.

But they’re not done yet.

“I’m not even gonna lie,” says Huerta. “I don’t think I could have done it without … these girls here, or any of the people who have been helping out, because we keep each other moving.”

Huerta adds that she’s also heartened by how the community of activists continues to grow. “Every time we do a verifier training, we see more faces, and that’s how I know that we’re growing, and we’re starting to see more people volunteer, and more people care.”

Warbington agrees. “I also could not imagine not doing this work,” she says. “I don’t want to envision a world where there isn’t this network of community members caring for their neighbors, right? And that really keeps me going. I feel like this work is so important. I feel like it is one of the most important things that we can do to keep our community safe.”

Carrillo admits there are days when she wishes they could “just be moms” and “be normal.”

“The thing that keeps me going is understanding that there are people who did for me what I’m doing for them,” says Carrillo. “I think each one of us believes that another world is possible because we’ve seen that in our community. We’ve seen that in the ways that we’ve moved with each other. And so I think it’s the hope that things can get better, and the hope that even if they don’t, we still have each other, no matter what.”