For more of our In Memoriam 2016 coverage, click here.

John Jay Hooker

Edward Gage Nelson

1931-2016

John Jay Hooker

1930-2016

Patricians, friends and opposites

By Bruce Dobie

Ed Nelson and John Jay Hooker grew up boyhood friends, the bluest of blue bloods, their families in the cream of Nashville society. When it came time to go to college, they enrolled at Sewanee together and became roommates. Later in life, they were in business together, at Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken, one of the most fabled Nashville business enterprises of all time. Listening to both, you could hear the same languorous, upper-caste Nashville accent, which, I guess, will be gone in about 20 years.

Never were there two more different people.

Ed was measured, mannered, diplomatic, steady-as-they-go, innately optimistic, curious about others, with a bantam-rooster physique. John Jay was tall, meteoric and polarizing, came with force, knew manners but could have cared less, was optimistic when the demons were at bay, and found curiosity in others more often as a means to embarking on some grand project than as an end in itself.

Ed was president of Belle Meade Country Club, a sign that you can balance a checkbook and also are considered a great guy. When he was in the money, John Jay belonged to both Belle Meade and Richland country clubs, a rare extravagance. When Richland was desegregating and John Jay and a few others met to get local black businessman T.B. Boyd accepted into Richland, John Jay told the group not to worry.

“I’ll get him in,” he told them.

“How will you do that?” the others asked.

“I’m going to tell the board a bunch of great things about him. Then I’m going to say that if they let him in, I will resign.”

Their brief period of time working together was at Minnie Pearl’s in the late 1960s. Hooker convinced Nelson to join as president. Hooker once told me, “I didn’t know my ass from a chicken. But when I saw what Kentucky Fried Chicken was doing, I knew I could be the clear No. 2.” (Nashville serial entrepreneur Jack C. Massey, later the co-founder of Hospital Corporation of America, was the money behind taking KFC nationwide.)

Minnie Pearl stock shot up to the moon. Everyone who was anyone bought some — including then-Congressman Richard Fulton, Tennessean publisher John Seigenthaler and businessman Bronson Ingram, who later sold some of his holdings and told his wife Martha to build a swimming pool, which to this day is named after Minnie Pearl. But then, in one swift and terrible investigation, federal regulators brought the company down for alleged stock puffery. As Nelson later told local writer Bill Carey, “Being president of the company was like being shackled to the train tracks when you know there is a train coming right at you.”

At his heart, Nelson was a banker. He was born into a long line of them — his forbears founded the Nashville Trust Co. in 1878. He spent 21 years at Commerce Union Bank, one of the city’s big three locally owned banks in its day, where he rose to chairman-CEO. Later he formed his own merchant bank, Nelson Capital, which, among other investments, helped Albie Del Favero and me start the Nashville Scene. He was extraordinarily active in civic affairs, serving on the Vanderbilt board of trust, which at the time was as blue-chip a board membership as there was in this town, and chairing the board of VU’s Medical Center.

Nelson wasn’t the boring banker, though. After college, he began what would become a long relationship with Japan, which commenced during a stint in the Army after college. “Spy” probably best captures what he was up to, although his official obituary more delicately described his work as existing in the Army’s “military intelligence division.” It was there, hunting communist agitators in the 1950s, that Nelson learned Japanese and made lifelong associations with Japanese leaders, helping pave the way for Nissan and other Japanese manufacturers to establish operations in Tennessee. He later received the highest award Japan bestows on noncitizens: “The Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays, with Rosette.”

One other thing about Ed: As president of Belle Meade Country Club, he oversaw the acceptance of the club’s first Jewish and African-American members. Previously, he had seen to the admission of a Jewish member at the Cumberland Club, then an important meeting place for the downtown business crowd. Ed loved people of all stripes and bore an open-minded curiosity that both made him special and improved this city.

Hooker once told me that Ed Nelson had the finest financial mind of any single individual he had ever met. At this point, I should say that Hooker certainly did not, even though at various points in his lifetime he was worth tens of millions of dollars. What Hooker did have, though, were two immense assets. First, he had the finest business and political imagination of any individual I’ve ever met. “I can see around corners,” he often said. He claimed HCA was his idea, which I can’t prove, but is perhaps true.

%{[ data-embed-type="oembed" data-embed-id="http://chirb.it/OKdEv4" data-embed-element="aside">

A serious two-time candidate for governor, and an early and outspoken supporter of civil rights, Hooker imagined a clear path to the presidency of the United States, thinking a Southern Democratic governor would assume the role after Nixon. History shows we ended up with Jimmy Carter. I do believe that had Hooker been elected governor, and had Minnie Pearl not gone under, he would have had a real shot at the White House.

Hooker’s second great gift was that he absolutely owned the English language — to hear him speak was to bear witness to unimaginably perfect oratory. In his heyday, he deployed this great gift before thousands of screaming supporters, from courthouse square to courthouse square. “I once asked John Seigenthaler, before Seig died, who was the greatest political speaker he had ever heard,” recalls local political impresario Tom Ingram, “and Seig didn’t miss a beat. He said it was Hooker.” Hooker himself used to put it like this: “I do love the sound of my own voice.”

The Hooker résumé included: co-owner and publisher of the Nashville Banner; chairman of STP Motor Oil; president of United Press International; founder of Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken; and a close adviser to Bobby Kennedy. Perhaps most importantly, he was a one-man band with a Rolodex, who focused on numerous political efforts, local and national. Hooker died penniless, but I look back on my last visits with him in his Centennial Hospital room and marvel at how he was then envisioning the presidential contest of 2016 being the perfect opportunity for an outsider.

Ed and I always ate at Vanderbilt’s University Club at the same table — he always ordered a BLT, hold the lettuce. Everyone knew him and spoke so politely to him, and he would always speak politely back. “How’s Laura Lee and the kids?” Ed would ask me as we sat down.

Hooker and I always ate at a restaurant of his selection, a place that he thought he could expand across the nation and take public. He put salt on everything. The last pla ce we ate together was a new hot chicken restaurant. “I think I can take this concept to Times Square tomorrow, you hear me?”

Bruce Dobie was the founding editor of the Nashville Scene as an alt-weekly in 1989.

For a slideshow of Nelson and Hooker, click here.

Peter Fyfe

1924-2016

Organist and mentor

By Richard Webster

My first encounter with Peter Fyfe was at my audition to study organ with him. I was 14. To this Baptist boy, the mysterious downtown “Christ Church, Episcopal” might as well have been the Vatican. Peter, smartly turned out in a suit and tie, met my mother and me at the church door. I later realized no one ever saw Peter without a tie, except maybe Lois, his wife and musical partner. Though he was born and raised in West Tennessee, you’d think Peter was from Oxford or Cambridge — in a beguiling rather than pretentious way.

Peter was a conscientious teacher, consummate organist and church musician, and beloved mentor. As the organist and choirmaster of Christ Church (now Cathedral) for 35 years, Peter directed a music program on par with those of America’s most prominent churches. He consistently broke new ground, commissioning dozens of works from an array of composers, enriching the sacred repertoire. Peter and Lois led the superb Christ Church Choir in music that was both tasteful and provocative. And they did so with dignity, thoughtfulness and humility.

Over five decades, Peter quietly coached and cajoled his organ students. He never raised his voice or embarrassed a student, but he was uncompromising. If I appeared at a lesson with dirty hands and fingernails, he would send me to the washroom for paper towels to clean the organ keys. No lecturing, no scolding. Just clean hands and keys.

Peter’s former students occupy church and teaching positions across the land. We owe him our sense of order, discipline and restraint. When he retired from Christ Church in 1994, I asked Peter what he would do next. With his signature self-effacing humor, he replied, “Oh, I’ll be running the vacuum for Lois in the shop.” As the founder of Lois Fyfe Music, from the basement of their Blair Boulevard home, Lois tirelessly shared with customers around the globe her encyclopedic knowledge of choral, organ and orchestral repertoire. As Lois had done for Peter at Christ Church, he was now her helpmate — penciling in prices on music copies, filling orders and being her vacuumist.

Peter Fyfe gave Nashville’s “Music City” moniker a holier patina. For his incalculable contributions to church music in America, and for his guidance and patience in shaping this young, impressionable organist, I am grateful. Hardly a Sunday passes, at the organ or in front of a choir, when his voice doesn’t beckon my ear — quietly encouraging, shaping and inspiring.

Shirley Caldwell-Patterson

1919-2016

Environmentalist, visionary

By Margaret Littman

The lore behind the founding of the Cumberland River Compact, the nonprofit that works to protect the region’s watershed, started in 1997, when Shirley Caldwell-Patterson watched Vic Scoggin’s film about his feat swimming the entire length of the then-polluted Cumberland River. Caldwell-Patterson, a native Nashvillian and granddaughter of the founder of what would later become Southern Bell, was horrified by the conditions of the river. An avid outdoorswoman, Caldwell-Patterson, then 79, pulled two friends together to launch the grassroots group.

I had heard this story many times, but it wasn’t until I sat in Richland Place, where Caldwell-Patterson was living in 2011, and heard it again from her mouth, that it clicked for me: the domino effect of activism. Scoggin was one person who swam 696 miles in a dirty river. Caldwell-Patterson was one person who was moved by his action. And down the line.

During my tenure volunteering on the board of the Compact, Caldwell-Patterson was passionate about creating a River Center, a place for the group to bring in more people to the work of protecting our waterways. I admit I couldn’t see her vision in those days. We met at Richland Place or board members’ homes or Germantown’s repurposed fire hall. The leap from not having any permanent space to having a premier piece of real estate on the river, looking out at the skyline, was something I couldn’t see. But Caldwell-Patterson could. And she wasn’t afraid to tell me — or anyone else — I was wrong.

Thanks to her leadership, the Compact does have a River Center now, in the Bridge Building on the east bank, where more people than ever get to learn about the importance of the river to the city and the region — and find out how they can get involved to help — while enjoying one of the best views in Nashville.

Caldwell-Patterson passed away in May, having told some of her Compact friends, “As soon as I convince at least some of mankind that we cannot continue to befoul our earth and expect to survive as a species, I’m ready to move on.”

Consider me convinced, Shirley.

R. Clay Isaacs

1962-2016

Owner, Lumen Lamps and Shades; key supporter, Nashville CARES and Planned Parenthood

By Bobby Smith

Clay talked me off the proverbial ledge on more than one occasion and reassured me in a way only he could — letting me know that it will all be OK. He was my buddy, my life coach and my career counselor, even advising me on matters of the heart. He knew me better than anyone. He could sense if I had a bad day or if something was bothering me. More often than not, he was right, and we talked it over, and by the time we were done — and maybe a Fireball or two later — all was right with the world. Those were our therapy sessions and a little escape from reality. I would give anything to have had just one more nightcap.

More than anything, losing someone you love makes you think harder about every moment. It makes you feel the weight of things, even something silly like a cartoon character or the sound of an obnoxious bird. It makes you treasure the moments that will never come again, and hope for the ones that will or could. All I can do is try to welcome the future while honoring the past, and hope that if Clay can see me, he is proud. Even if he would get one more joke in at my expense.

Matthew Walker Jr.

1941-2016

Freedom Rider

When we got to Mississippi, National Guardsmen boarded the bus with fixed bayonets on their rifles. They stood the length of the bus in the aisle. I said to one of them, ‘Man, that’s a mighty fancy rifle you’ve got there.’

“His response was, ‘I ain’t got one word to say to you.’ [Laughs]

“ ‘Yeah,’ I said to myself. ‘These are our protectors.’ ”

(Matthew Walker Jr., quoted in Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders, by Eric Etheridge. Atlas & Co., 2008)

Johnny Howell

1943-2016

Greengrocer, ‘The Bradley Tomato Man’

By Kay West

If you’ve eaten a locally grown Bradley tomato in Nashville, there’s a good chance it came from Johnny Howell, referred to in his obituary by his nickname, “The Bradley Tomato Man.”

Howell was raised and lived his whole life on Hester Beasley Road off Highway 100 in Linton, better known in Davidson County as Bellevue. Though Howell’s day job was working as a lineman for NES, the family always had a produce business, operating a country store, delivering vegetables to local fast-food chains and selling from a truck out of the old Nashville Farmers’ Market on Jefferson Street. When Howell retired from NES about 25 years ago, he devoted himself full time to farming on 300 acres he leased across the road from the family property where he and his brother had built their homes. “He just loved to grow stuff,” says the youngest of his three children, Johnny J. Howell, nicknamed “Peanut” by his father.

He especially loved to grow Bradley tomatoes. “Lots of people grew red tomatoes, but not many did pink tomatoes like Bradleys,” Peanut Howell explains. “In good years, we put out as many as 150,000 Bradleys a season. We grew about 12 kinds of tomatoes, but he was known for Bradleys.” Since 1995, people have found them in Farm Shed 1 at the current location of the Farmers’ Market on Rosa Parks Boulevard, at seasonal Howell’s Farm tents in Green Hills and Belle Meade, and at their own stand on the farm.

When the Farmers’ Market started the weekly Vanderbilt Market six years ago, Howell’s was one of the first three farms to sign up and was key to its initial success, according to market director Tasha Kennard. She says she always got a laugh when she called his cellphone and got his ring-back tone: Jason Aldean’s “Big Green Tractor.”

Per his wishes, Howell was laid out in his favorite pair of well-worn overalls and Howell Farms ball cap. After the service at Harpeth Hills Funeral Home, the hearse carrying his casket drove down Hester Beasley Road and around the fields one last time. Back at Harpeth Hills, his casket was placed on a farm wagon hitched to his beloved big green tractor, which took The Bradley Tomato Man to his eternal plot on earth.

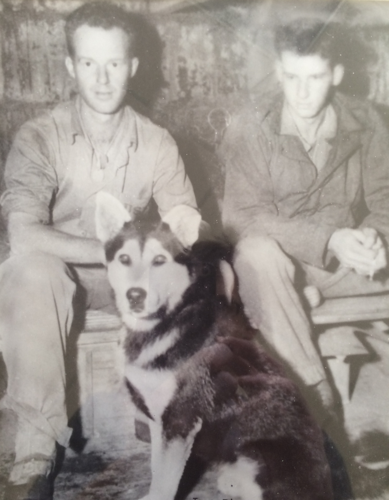

Dale Quillen (left) and dog Tippy on Iwo Jima

Dale Quillen

1925-2016

Defense attorney

By J.R. Lind

Mike Flanagan took a job alongside Dale Quillen on a Friday.

The prominent defense attorney said he had to drive down to Dayton for an appearance hearing in Rhea County the following Monday, and told Flanagan to come along so they could discuss business.

But when they got there, the judge said this was no simple first appearance. It was, in fact, time to proceed with jury selection. Quillen felt rooked, and told the judge he was in no way ready for trial. The judge, having none of it, said if the defense wasn’t ready to proceed, they could spend the weekend in the Rhea County Jail for contempt.

“Mr. Quillen, what are we going to do?” Flanagan asked.

“I fought at Iwo Jima. I’m not afraid of the Rhea County Jail.”

“But, Mr. Quillen, I wasn’t at Iwo Jima!”

Sensing the judge wouldn’t back down, Quillen told him that if he was to be charged with contempt, he’d need to find counsel and requested the hearing on the charge be postponed. The judge, perhaps a bit impressed, agreed. Quillen and Flanagan drove to Chattanooga, found an attorney, and the whole matter got sorted out.

Quillen died Aug. 13 at 91, another character from a wilder time in the city’s legal history gone, another hero from the Greatest Generation gone.

Born in the wilds of the Smoky Mountains, Quillen left home in 1943 — at just 17— to join the Marines. As a member of the Third Division, he helped free Guam from Japanese occupation and fought at Iwo Jima, part of a group of leathernecks teamed up with specially trained dogs to root out Japanese soldiers from tunnels and caves in the hell of the South Pacific.

Quillen earned a Purple Heart during his service — one of his hospital mates was Sterling Hayden, who earned fame for playing, among others, Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove and corrupt police captain Mark McCluskey in The Godfather.

After his discharge, Quillen came home, eventually winding up at the YMCA Night Law School in Nashville, from which he graduated in 1956. He made an early name for himself by crafting a pioneering defense for bootlegging — considering where he was reared, a perfect match — and other such mischievous vices. His first case involved an out-of-town businessman caught up in some sort of shenanigans at the Merchants Hotel. In a nod to that, Quillen’s 90th birthday party was held in the upstairs dining room at the name’s-the-same restaurant there.

He grew to be well-respected on both sides of the bar, earning a reputation for fair dealing and a commitment to the rights of the accused. This respect was perhaps no better manifested than in 1978, when he faced federal charges because he agreed to represent infamous Nashville auto thief and jail-escape artist Rabbit Veach (who himself died in 2016), with the defendant under an assumed name. Veach was found out, but not because Quillen ever gave up the ruse. He asserted that attorney-client privilege was inviolate and that he had no obligation to reveal the actual identity of his client. A federal jury, after hearing testimony from ethics experts, agreed and acquitted Quillen. Quillen’s attorney in the matter? James Neal, former Watergate special prosecutor and a frequent adversary of Quillen as the U.S. Attorney in Nashville.

But Quillen was no saint, either. In 1992, he made headlines for an elevator altercation with his then-wife’s divorce attorney (this was divorce No. 3 for Quillen), William Willis. Quillen said Willis hit him in the groin with his briefcase and bit his finger. For his trouble, Willis came out of the elevator with a broken nose and cut-up face. Quillen, then 68, still had the fighting spirit of a Marine, even if it was occasionally unrestrained.

With Quillen died a man who was a hero to his country and a true character of the legal community — his memorial service at the veterans cemetery drew plenty of judges and fellow members of the defense bar, as well as several current and former district attorneys-general. But Nashville lost something, too: the old-school courthouse lawyer, a now all-too-infrequent species.

Law school graduates who want the fortunes of the corporate firm spend too much time crafting briefs in backrooms, and when they do head to court, find themselves nervous at asking a judge face to face for even the most mundane requests. Others, who want careers in politics, opt for the DA’s office. Rarer every year is the new lawyer willing to stand up for the accused, spending untold hours in General Sessions and at the jail, providing a vigorous defense.

Dale Quillen vigorously defended Americans in the South Pacific. And then for six decades, he did it again and again.

Derek Murray

1962-2016

One of more than 80 homeless people who passed away on Nashville’s streets in 2016

By Amanda Haggard

Derek Murray wanted to die on his own terms. After his life became a revolving door of hospitalization and living on the streets, he wished to pass pain free, with a beer in hand and family and friends surrounding him.

At first, when outreach workers found Murray, 54, near death in his tent, he didn’t want to leave. It took some begging and pleading to get him to come in from the home he’d built in his tent to the safety of a hospital. But once outreach workers figured out how to accomplish his terms (namely, how exactly to bypass some rules to allow him to drink in the hospital), he agreed to go.

Vanderbilt psychiatrist Sheryl Fleisch, who also founded Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Street Psychiatry Program, said a few words about Murray at the annual Homeless Memorial on Dec. 16, where nonprofit workers, government officials and community members joined to honor the lives of those lost, and to recognize the agonizing poverty and housing issues that plague the city.

Murray was one of more than 80 people who passed away while unhoused in Nashville in 2016 — a handful more were listed on the memorial’s program as formerly homeless, and a couple weren’t included because they passed after the program had been printed.

Murray died on Nov. 27 with a roof over his head in Alive Hospice, though he spent a large portion of his adult life homeless.

“It’s ironic that he died indoors, but I’m happy that we were able to give him that, at the least,” Fleisch says. “Derek wasn’t always easy to deal with — he could be a real pain in the ass. He was complex, but in the end, he was able to pass with dignity, and on his own terms.”

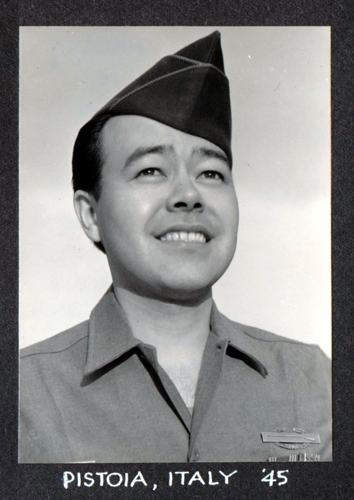

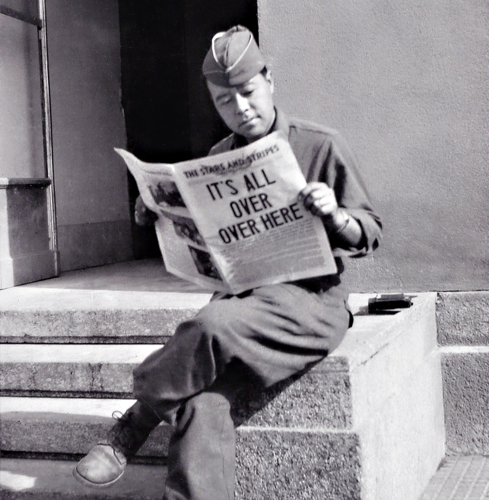

Togue Uchida at the end of fighting in the European theater.

Togue Uchida

1917-2016

Photographer and war hero

By Steven Hale

It’s almost impossible to say how many people Togo Ingvar Uchida photographed over the course of his life, but a conservative estimate gets you into the hundreds of thousands, with him snapping the shutter more than a million times.

His career in photography began when he got out of high school, and lasted until three years ago, when at the age of 96 he fell and hit his head — he’d stepped outside, camera in hand, to photograph the results of a winter storm. Taking pictures was the only job he ever had, save for the few years he spent in the employ of Uncle Sam as a member of the 442nd Infantry Regiment in World War II. The medals he earned as a soldier hang in contrast to the mistreatment he and his brothers in arms faced from their own country. The 442nd, almost entirely made up of Japanese-Americans — some of them drafted from internment camps — is the most decorated unit in American military history, its members having been continually called into the most perilous situations the war served up.

His life’s work is catalogued and stored in rows of filing cabinets in the corner room of an unassuming brick building in a Bellevue office park, decades of negatives acting as the receipts for a million captured moments. But you can also hear it, in the voices of two of his granddaughters, Samantha and Cameron, who remember neither a soldier nor a photographer, but a fun-loving grandfather who often won at Scrabble and always ate dessert before dinner. Uchida’s youngest son, Tom, who runs the business now, remembers an almost supernaturally gentle man who “only yelled at me once in his life … and it was because he was standing up for my mom.”

He died in August at the age of 98, an American hero known to generations of Nashvillian brides and high school seniors as the kind man behind the camera.

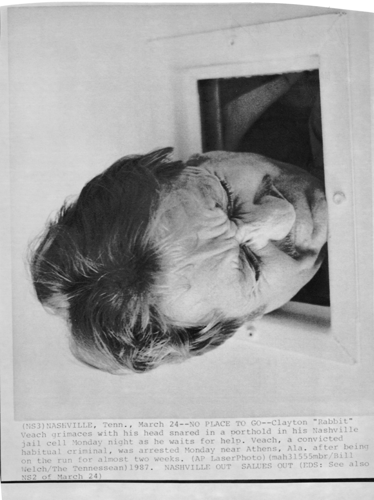

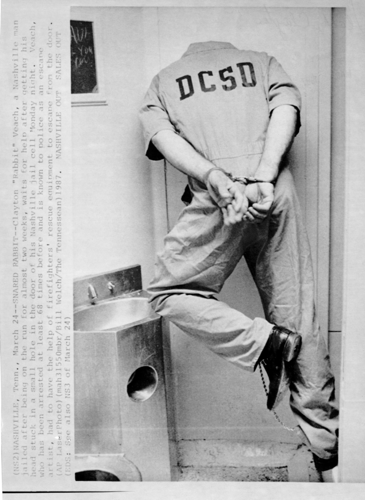

Clayton “Rabbit” Veach, jailed after being on the run for almost two weeks, waits for help after getting his head stuck in a small hole in the door of his Nashville jail cell Monday night. Veach, who had been arrested at least 68 times to that point, had to have the help of firefighters’ rescue equipment to get out of the door. (1987 photo)

Clayton “Rabbit” Veach

1941*-2016

Escape artist

By E. Thomas Wood

A family-penned obit for Clayton Veach in January told of a man who “loved to work on cars, race them and show them off,” who “knew no stranger and always showed compassion and love for everyone.”

There’s no solid reason to believe such a portrayal was off the mark, but it left out a few details. From his teen years in the 1950s until at least the 1980s, “Rabbit” Veach — so named by Nashville jailers for his uncanny ability to escape their grasp — absconded from police custody so many times that he became a minor folk hero.

Accounts of Veach’s escapes from the early 1960s carry the bylines of such later-legendary journalists as the Nashville Tennessean’s Jim Squires and Bill Kovach. By the time “Rabbit” fled the Davidson County Hospital’s psych ward in October 1963, barefoot and in shackles, he had tallied seven escapes. There would be more — from Nashville’s jail, Sumner County’s, and the Merle Haggard-approved hoosegow in Muskogee County, Okla., among other custodial venues.

By 1964, The Tennessean was calling Veach “Tennessee’s champion jailbreaker” as authorities moved him to the safe confines of the Tennessee State Penitentiary. “We had to take him out there,” chief deputy sheriff Fate Thomas told the morning daily. “We were all about to have a nervous breakdown, worrying about whether Veach would escape again.”

There is a dark side to the Veach story, as Kovach reported in 1962. Four years earlier, the day before his brother would have graduated high school in Franklin County, Clayton had watched helplessly from the edge of a swimming hole as his sibling drowned. “Ever since then, I’ve been getting in trouble,” he told the reporter. “When they caught me, I would run, hoping someday one of the officers would shoot and kill me.”

As of 1987, just before Veach fled the Metro Courthouse in the midst of his trial for a truck-theft charge, he said he had been arrested 68 times since 1959. Despite a habitual-criminal conviction, he seems to have spent his autumn years at liberty and in relative peace.

*Metro Criminal Court Clerk records show Veach as born on Christmas Day of 1940, 1941 or 1943.

Lelia Martin Gilchrist

1947-2016

Architect

By Christine Kreyling

Lelia Martin Gilchrist’s most significant contribution to Nashville’s urban design, in the firm she established here in 1997 with Larry Woodson, her husband and partner, was to show how buildings in the modern style can make a positive contribution to the urban cityscape.

The house they designed for themselves in Hillsboro-West End is Exhibit A. A clearly modern building, the Woodson-Gilchrist house (2003) nevertheless exhibits the setback, massing and hipped roof of the foursquares scattered throughout the surrounding neighborhood. The broad porch has a simple shelf as well as chairs for seating. The facade, except for the wood door signaling entrance, is glazed to present an open face to the street. The L-form of the house edges a courtyard whose brick wall — concisely bent to preserve a large tree — affords transparency to living and sleeping quarters. The patio and lawn are an extension of the house’s interior, extracting maximum utility from the small urban lot. A garage with upstairs apartment is sited on the rear alley, relegating cars to back of the house.

Woodson-Gilchrist’s multi-family East End Lofts (2007), on East Nashville’s Woodland Street, exhibits a similar sensitivity to urban necessity. First-floor units are raised above sidewalk level and fronted with stoops, screen walls and street trees, protecting the privacy and access to daylight of residents. Upper-story units have balconies, or rooftop decks in the case of the penthouse units, which are set back from the primary facade to minimize the impact of the massing on the street.

To realize the skill and attention to detail of the Lofts, compare them with a later multi-family complex just down the street. At 715 Woodland, first-floor units are at street grade, forcing residents to keep windows covered, blocking natural light and the curious gazes of passers-by. There’s nary a tree or porch in site.

Lelia saw no contradiction between her devotion to modernism and her simultaneous dedication to historic preservation. In Nashville she worked with Larry on the restoration and renovation of East Nashville’s Carnegie library (2000), a building that had suffered 1960s degradations.

“I remember Lelia’s excitement when she found the original wood moldings under the drop ceiling,” says Donna Nicely, who was then the director of the city’s public library system. “And she tracked down the original tables” that had been dispersed throughout Metro as mere utilitarian objects, and “had them refinished and adapted for computers. Lelia had an eye for detail.”

Remembered …

Jeff Carr, vice chancellor for university relations, general counsel and secretary, emeritus, Vanderbilt University.

Bob Hoover, World War II veteran and Air Force test pilot known for his aerobatic stunts.

Carol Ann Jenkins, R&B preservationist and restaurant owner.

Eric Rosenfeld, Holocaust survivor and World War II counterintelligence veteran.

Sandra Thomas-Trudo, director of epidemiology at Metro Health Department.