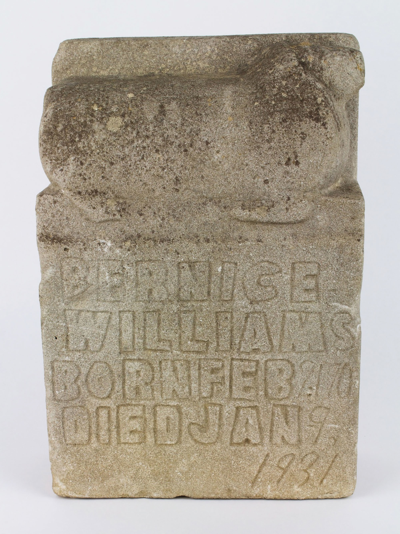

A headstone carved by William Edmondson

We could spend our time together this week talking about how some Sonic the Hedgehog-looking politician wants to strip kids of their right to a free education, or how a former state senator moaned so loudly that he got out of prison after just two weeks — despite the fact that kids in Tennessee are often put in prisons as children for the rest of their lives. There are 16-year-olds who have been treated more unfairly that Brian Kelsey, and they do their unjust time with more dignity than Brian Kelsey.

It makes me sick.

So instead, let’s try to solve a bit of a history mystery. Cast your mind back to October 2019 and the Scene’s Death Issue. Arts editor Laura Hutson Hunter (shout-out to my girl!) wrote a story for that issue called “Edmondson’s Folly: The ‘grave’ mistake made by one of Nashville’s greatest artists.” In it, she and Nashville treasure Jim Hoobler talk about a headstone carved by William Edmondson that’s now in the state museum’s collection.

Bernice Williams’ tombstone is among the most venerable in American history, but her family didn’t want it.

From Laura’s story:

It’s with those tools that he likely made Bernice Williams’ gravemarker, which is part of a collection of Edmondson’s sculptures at the museum, along with a collection of Edmondson’s sculptures. The lamb on the top of the tombstone is similar to the sculptures Edmondson became famous for — in the master checklist from the 1937 exhibit, a piece titled “Lamb” was listed as having sold for $40. But the gravemarker is in excellent condition, simply because it was unwanted by the family who commissioned it.

“The supposition is that Edmondson had misjudged the size and spacing for his inscription,” says Jim Hoobler, the Tennessee State Museum’s senior curator of art and architecture. The birth date on the stone is 1906, but only the first three digits of that date are visible on its surface. The “6” appears on the side.

“It remained in [Edmondson’s] stone yard until his own death,” says Hoobler.

This is all intriguing and fun. You’ve got unrecognized artistic genius and a family that let the chance to own a sculpture by one of Nashville’s most famous artists slip through their hands because of some spacing issues. Delightful. Who is this Bernice Williams, and who is this foolish family?

Bernice Williams! Please step forward into the spotlight of history. Bernice Williams. Bernice Williams?

[Crickets.]

I recently talked to Morgan Byrn over at the state museum, and she told me that according to museum records, the headstone was acquired in 1951 from William Edmondson’s nephew. The nephew told them that William had been commissioned to carve it in 1933 by Robert Williams, Bernice’s husband, who then — for whatever reason — never came and got it. Cool, now we know the fool. Robert Williams.

Let’s go to the city directory. In 1930, when Bernice was alive, there were five Black Robert Williamses living in Nashville: a single guy who lived on Edgehill near Edmondson; a guy who ran a restaurant near Edmondson’s house on 12th Avenue South, who had a wife named Aggie; a barber and his wife, Dessie, on Gallatin; a porter up in North Nashville; and a single guy who lived on Hawkins. No one with a wife named Bernice. I even checked Williamson County, and the only Robert Williams I could find the right age was white.

How a headstone in a Madison cemetery connects to Edmondson, Tennessee Gov. William Carroll and Old Nashville's Black community

OK, well, we have a birth date and a death date — so we can find a Bernice Williams who died on Jan. 9, 1931, right? No.

There is, however, Birdie Compton.

Listen, right now, I know many of you were like, “Oh, shit!” But five, maybe 10, of you heard dramatic “dun Dun DUN” music in your head in addition to the “oh shit!” and I promise, I will bring the rest of you into the more scandalous circle in just a minute.

But first, let’s lay out the facts as we know them about Birdie Compton. We know from her obituary that her parents were Richard and Callie Batey. The first time we find her in the census, in 1910, she is Bernice Batey and living with her parents and siblings in Rutherford County. By 1930, she is living with her husband, William Porter Compton, and their daughter, Elizabeth, at her in-laws’ place on Seventh Avenue South here in Nashville. Her father-in-law was Charlie Compton. On Jan. 9, 1931, she died of bronchial pneumonia brought on by tuberculosis. She was buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

I believe that Birdie Compton is who the Bernice Williams headstone was made for. Right age, right first name, right death date, and there are no other candidates. Plus, three Robert Williamses close enough to Edmondson to have stopped by to order the stone. It’s easy enough to concoct a story in your head: They were having an affair and were desperately in love and he wanted her to be his wife, but fate and TB ruined it. So in his grief, he had this headstone made, with no way to place it on the grave of the woman he loved.

But I went through some shit in my younger days, and when I die, if there is a headstone carved with my first name and some other last name on it, I will not be surprised. Disappointed? Scared as hell? Sure. But surprised? No.

Birdie was a young mother who lived with her in-laws and had tuberculosis. That is a tired woman who is always in someone’s company. So I actually think it’s more likely that some stalker who had a one-sided “relationship” with Birdie ordered this headstone and couldn’t come get it — because where was he going to put it?

The famed Black Nashvillian's sculptures are art for living with and being a part of the everyday

Either way, Nashville was a small town back then. People knew each other and knew of each other. If a young mother died of consumption in William's neighborhood, he likely would have known about it. As would have everyone else. William Edmondson didn’t make headstones for people he didn’t know or know of. He had to have known there wasn’t any Bernice Williams. But he left that headstone in his yard for the rest of his life.

Why? I don’t think it had anything to do with Birdie. I think it may have had to do with a century-old grudge.

In his essay, “From Plantation to the City: William Edmondson and the African-American Community,” from The Art of William Edmondson, Dr. Bobby Lovett explains:

Compton plantation taught Orange, Jane, and their children [including William] the cruel legacies of miscegenation, color, and class. The dark-skinned Edmondsons were merely field hands (earning perhaps ten to twelve dollars per month) working corn and other crops and serving as teamsters and livestock handlers. The mulattos got better jobs as blacksmiths, house servants, cooks, and stone masons. Not only were mulattos privileged persons on the Compton plantation, but some of them seemed to be members of the family, especially mulattos connected to Henry [Compton].

Birdie’s husband’s grandfather, Miles, was enslaved by Henry Compton, same as at least William’s mom. The funny/sad part of all this — if indeed there were hard feelings between William and Porter Compton’s people — is that this branch of the Comptons and the Edmondsons all seemed to have the same negative opinion of their old enslaver, Henry Compton. Some Black Comptons might have been done OK by Henry Compton, but it doesn’t seem like that was true of this branch.

Still, the only likely candidate for Bernice Williams is Bernice “Birdie” Compton. But why was the headstone made with the wrong last name? We may never know.