I have a small collection of pictures of headstones that kind of look like they could have been done by noted Nashville sculptor William Edmondson, but I’m not quite sure. I have a list of questions I ask myself when I come across a possible Edmondson: 1. Did the person die when Edmondson was known to be working? 2. Are there other Edmondsons in the cemetery? 3. Did the person or the person’s family live some place where they would have crossed paths with Edmondson? 4. Is this a Benevolent Society cemetery? 5. Is there any lore about it being one?

There’s this headstone up in the Sons of Ham Cemetery in Madison that fits into that almost-but-not-quite category for me. It’s kind of shaped like an Edmondson headstone. It’s definitely handcarved, and the letters that are still legible kind of look like Edmondson’s letters. Plus, the 2s look identical to Edmondson’s, and the 9s also look like his fetus-shaped nines. If you were just judging by number shapes alone, this is an Edmondson. But it’s on my probably-not list for two reasons: The letters are raised, and I don’t know of any known Edmondson with raised letters; and the person died in 1912, which is way before Edmondson was known to be carving anything.

Still, it has been nagging at me. At the least, I wanted to satisfy myself that there wasn’t a way for this person and Edmondson to have crossed paths. This was made difficult by the fact that the person’s name has almost completely broken away. At first, all I could make out was an M at the start and a Y at the end. I thought maybe it was someone from Nashville's Kelley family, because there are a ton of them in that cemetery and they’re the only family whose name ends in Y who lived in that area and had family members dying about that time. None of them panned out.

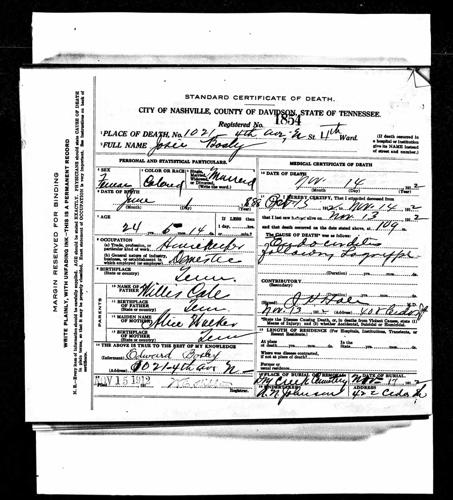

Josie Bosley's death certificate

I went back to the cemetery to try to make out more of the last name, and after staring at the stone for a good while and feeling around, I decided the last three letters were "SLY." Lo and behold, there’s a Bosley in the cemetery — Josie Cole Bosley, who died in 1912. So the M is probably for "Mrs." I found her death certificate, and it appears she died of “endocarditis following lagniappe.” The only thing I know lagniappe for is being a tasty little treat, or like a tiny luxury down in New Orleans. I have no idea how it might give someone a heart infection. Points to whoever can figure out what that word actually is. Elderly pharmacists who are used to deciphering doctors’ handwriting, this is your time to shine.

So then, for this longshot to pay off, I had to find some way for her and Edmondson or her family and Edmondson to have crossed paths. Dear reader, I did not. I did, however, find a story of one of the strangest fights over a grave marker to have ever happened in Nashville history.

OK, so Josie’s husband (sadly, they were married very briefly, like mere months, before she died) was Edward Bosley, who was also the informant on her death certificate. At this point I got sidetracked by the exploits of his children from his second marriage. I won’t get into it, but suffice it to say that, if a Bosley from the Madison area threatens to kill you, understand it’s a family tradition and flee for your life. Then I went looking for Edward’s older people. Edward (1883-1949) had a brother, Eugene (1889-1958), and they had a mother, Lena (1845-1900). As far as I can tell, there only ever was one woman named Lena Bosley in Nashville. She attended Fisk University in the early 1870s. She was married to a man named Phillip Hockett or Hoggett Bosley. He was almost always called Hoggett/Hockett. Hoggett was born in 1852, and we don’t know when he died. Hoggett’s first appearance in the Census was in 1860. J.B. Bosley (54 and white), is living in District 23 with Alecy Bosley, (46 and "mulatto") and their children — Medora, John, Hoggett and James.

I was surprised by this — a white guy in the mid-1800s with a Black family, living out in the country like there’s nothing unusual for his time about this — but also not surprised when I learned that ol’ J.B. here was the grandson of James and Charlotte Robertson. In other words, not only was he living in a part of the county where white guys went to live with their Black wives unbothered, but like George Parker, he was doing like a lot of white men from the old ironwork families in Middle Tennessee did. And he was from one of those old iron families. (There’s not a good place to stick this information, but Bosley did own slaves too, and he was known for being pretty brutal about it.)

We know that this John Bosley is the son of John Bosley and Delilah Robertson because he’s named in his father’s will. However, we also know that a John Bosley roughly the same age as our John Bosley was in Mississippi in the early 1800s with John Sr.'s brother, Charles, and his wife, Sally, maiden name Hoggatt. Based on the fact that he named his son Hoggatt, I think this is the same John. Not Charles’ son, but Charles’ nephew.

So here’s the setup: Charles Bosley came back to Nashville after Sally died in Mississippi, and he settled along Richland Creek about where St. Thomas West is. There’s still a road there named Bosley Springs, and the springs were named after him. His nephew was married to a Black woman, and they lived north of town. In between them was the site of the construction of the state Capitol and the quarry the stone for the Capitol was being mined out of. (Fun fact: If you’ve ever noticed how the land north of Charlotte by Jack’s Barbecue is terraced, that’s because that’s this old quarry.) This quarry was owned by Samuel Watkins, who was the foster son of the Robertsons, and thus something of an uncle to John Bosley.

As the Capitol was being built, William Carroll died. (If you like stories about duels and fights, but you can’t get past Andrew Jackson being a genocidal maniac, might I introduce you to William Carroll, six-term governor of the state of Tennessee and obvious member of the Lollipop Guild?) So the state of Tennessee decided to put a fitting monument on his grave in the city cemetery.

Charles Bosley — the story goes — offered to give a boulder from his land out where St. Thomas is to be used for said monument. A group of free men of color who worked for the gravestone and monument maker Thomas Shelton showed up to get the boulder and bring it to town. According to later stories in The Tennessean, a massive fight broke out between these free men of color and Charles Bosley’s slaves, and this, for some reason, pissed Charles off so bad that he changed his mind. No, they can’t take the boulder. Carroll’s supporters can pound sand.

So, the free men of color muffled their wagon and came back in the middle of the night and stole the rock. They then took the rock up to the state Capitol, where they were able to hide it among all the stones being chipped apart to make the building. There, hidden among the other stones and stonemasons, they carved this eagle. The eagle was then deposited on top of William Carroll’s grave, where it sits today.

But this is another one of those stories that I think would have been heard two different ways here in Nashville. From the newspaper stories, it’s clear that white Nashville heard a story of Black men being ridiculous and fighting over who knows what. The Tennessean’s account just says the free men of color were verbally abusing the enslaved men, though it’s hard to guess what they could have been fighting about that would have been so bad that a white guy would pitch a fit about it. Are we supposed to believe that Bosley was defending their honor? Because that’s hard to believe.

I wonder if Black Nashville would have enjoyed that story because the men were able to abscond with the stone and then hide it and themselves among the crowd building the Capitol. But more than that, I wonder just who these free men of color were, and why they would go right by the quarry near the Capitol, past every bit of stone that Rock City (our nickname in the 1800s) was built on to go clear out west of town to get a rock. It’s Davidson County. You can’t go more than three steps without finding bare rock.

The story that ran in The Tennessean on March 22, 1943, provides an interesting clue as to who actually stole the stone. The grandson of Thomas Shelton, the man charged with erecting the monument, told the paper that “the Negro who initiated the theft of the stone later lost his eyesight through a premature blast and for many years prior to 1900 was accustomed to stand in front of the First Presbyterian Church and beg for nickels.”

Y’all, if this story is true, this seems like a guy who easy enough to find. A Black, blind beggar who sat on Church Street. I’ve got two plausible men. First up is James Robertson, who according to the Dec. 15, 1896, issue of the Nashville Banner, did beg in front of First Presbyterian. He’s in the right spot, but it turns out no one who knew him believed he was actually blind, because he was a crack shot. So probably not him. But back on Dec. 13, 1891, The Tennessean noted the passing of “the old blind negro who has stood for years at the corner of Church and High streets, generally at the foot of the Christ Church steps.” Though they don’t name him, they do say “he had been nearly blind for many years, and had worked at his calling as a stonecutter.” So he wasn’t always blind. And the Banner seems to have named him back on April 8, 1885: Stephen Barnard.

This, then, in a roundabout way, brings us to United States Colored Troops veteran William Bosley. Bosley worked as a stonemason after the Civil War, and he was a stonemason when he enlisted. He was even sent after the war to work at the National Cemetery down in Murfreesboro, and his Civil War enlistment papers state he’s from Maryland and a stonemason. In 1880, he was living in Nashville with his wife, two daughters and a pile of grandchildren. At least Charles and Adonis used their mother’s maiden name later in life. Charles followed in his grandfather’s footsteps and became a stonecutter.

Here's where we come full circle, though. Adonis Bosley, grandson and brother of the stonecutting Bosleys, lived at 807 Second Ave. N. in 1910. Eugene Bosley, the son of Hockett Bosley and brother-in-law of Josie with the mysterious tombstone, lived at 805 Second Ave. N. in 1910. Were these two families — William’s and Hockett’s — related? The white Bosleys and William both came from Maryland, but William didn’t get here until the Civil War, and the white Bosleys were here shortly after settlement. But white families felt no compunction about splitting up Black families, so it’s possible that white Bosleys in Maryland had sent some of William’s family here to their relatives, and so after the war, he came looking for them.

I think that, when Josie died in 1912, the most likely person to have carved that headstone was Charles Bosley.

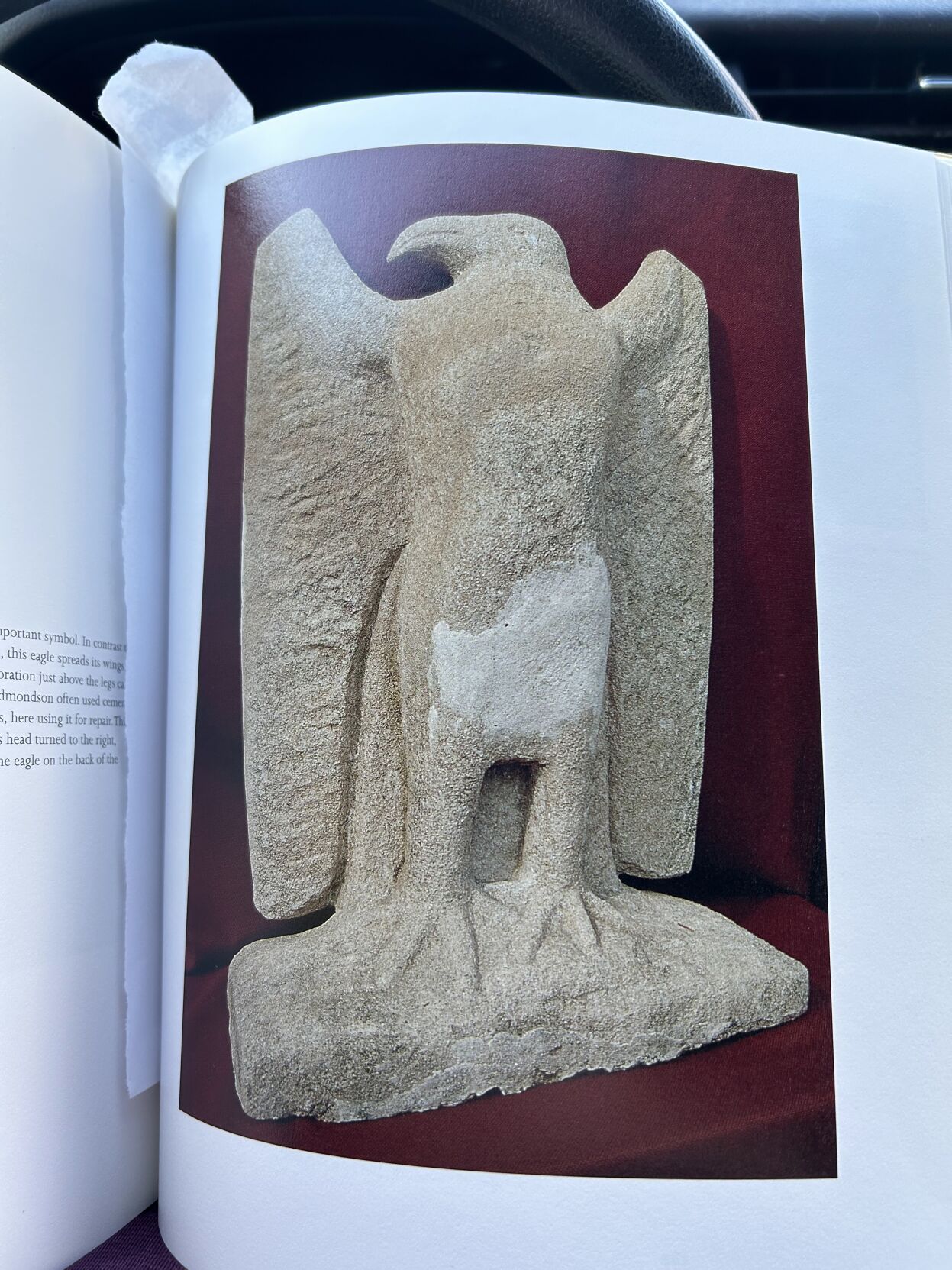

But I suspect this whole convoluted story may still link back to William Edmondson. This thing that looks like a turkey but is supposed to be an eagle is the carving on the top of William Carroll’s monument. Note how it looks like it’s about to start dancing to Zeddy Will’s “Cha Cha.”

An eagle carving on Gov. William Carroll’s monument

Now check this eagle that Edmondson carved — same head position, same wing position, and it too looks like it is about to break out into a TikTok dance.

William Edmondson's eagle

William Edmondson is considered an outsider artist because he is, supposedly, not in any artistic tradition. No one influenced him and he influenced no one. Except, if you look at that eagle/turkey that Stephen Barnard likely carved and the headstone that Charles Bosley likely carved — one in a cemetery in William’s neighborhood (in the shadow of the fort his dad and other family members helped build) and one in a cemetery where William placed a headstone — we’re seeing his antecedents, the artwork his artwork is in conversation with.

Not only do we get to live with Edmondson sculptures and the gravestones he made for his friends and family and neighbors, we get to live with the very stuff that experts have said doesn’t exist — the art that influenced and inspired him.