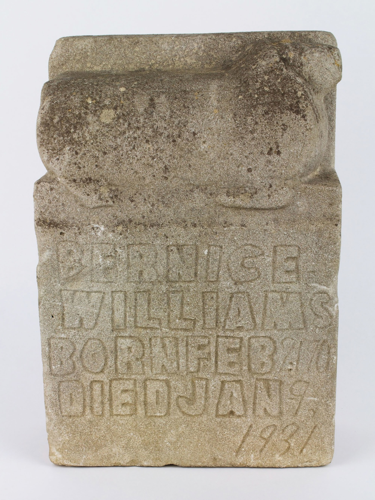

A headstone carved by William Edmondson

Bernice Williams’ tombstone is among the most venerable in American history, but her family didn’t want it.

The stone, which is currently in the archives at the Tennessee State Museum, was carved by William Edmondson. Born in Davidson County in the 1870s to formerly enslaved people, Edmondson came to art-making fairly late in life — in 1929, he heard a voice from God that told him to pick up his chisel and start carving a tombstone. And so he did.

Less than 10 years later, Edmondson became the first African American artist to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The 1937 exhibit included a press release stating that Edmondson “has had no art training and very little education, and has probably never seen a piece of sculpture except his own.”

Edmondson’s creativity, he said, was entirely God-given. In an August 1981 issue of Smithsonian Magazine, Edmondson is quoted as having said: “First He told me to make tombstones; then He told me to cut the figures. I do according to the wisdom of God. He gives me the mind and the hand, I suppose, and then I go ahead and carve these things.”

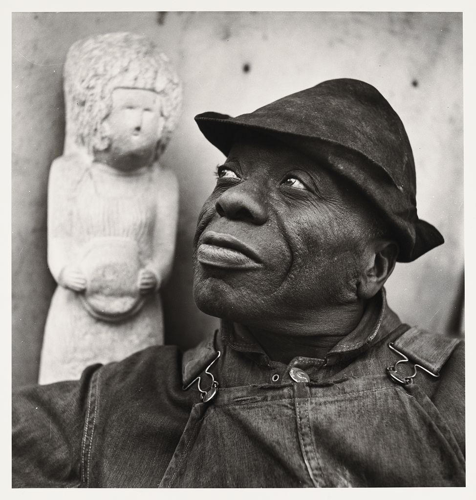

Photo of William Edmondson by Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Edmondson began his art-making career by making tombstones for families in Nashville’s African American community and members of his congregation at the United Primitive Baptist Church. For these, Edmondson worked primarily with chunks of discarded limestone from demolished houses — the only material he could acquire inexpensively, or sometimes totally free of cost. The rectangular blocks were formerly used as sills, lintels, steps and curbs. The limestone material was relatively soft, which was a necessary quality for a sculptor like Edmondson who worked with a sledgehammer and improvised tools, including chisels he’d fashioned from railway spikes. The tools allowed him to make a variety of textures on his stone, from smooth skin to pitted dresses to wooly animals.

It’s with those tools that he likely made Bernice Williams’ gravemarker, which is part of a collection of Edmondson’s sculptures at the museum, along with a collection of Edmondson’s sculptures. The lamb on the top of the tombstone is similar to the sculptures Edmondson became famous for — in the master checklist from the 1937 exhibit, a piece titled “Lamb” was listed as having sold for $40. But the gravemarker is in excellent condition, simply because it was unwanted by the family who commissioned it.

“The supposition is that Edmondson had misjudged the size and spacing for his inscription,” says Jim Hoobler, the Tennessee State Museum’s senior curator of art and architecture. The birth date on the stone is 1906, but only the first three digits of that date are visible on its surface. The “6” appears on the side.

“It remained in [Edmondson’s] stone yard until his own death,” says Hoobler.

It’s particularly unfortunate that Edmondson’s own tombstone has been lost. Mt. Ararat Cemetery, where he was buried in 1951, lost its records to a fire. His legacy, however, is stronger than ever. In 2016, Edmondson’s sculpture “Boxer” set a new world record for any work of outsider art — it sold in an auction at Christie’s for $785,000.