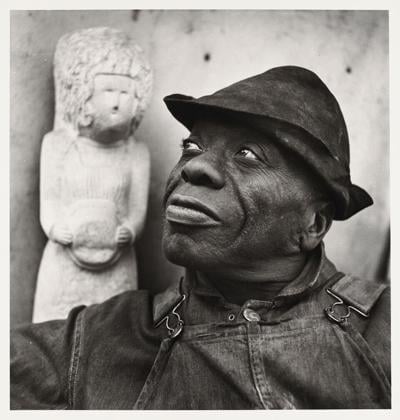

William Edmondson

I spent a lot of time over the holidays wandering around Mt. Cemetery and Greenwood Cemetery looking for headstones carved by famed Nashville artist William Edmondson. It was depressing. There are quite a few you can’t read the writing on anymore. One of the really nice ones has a big chip out of it. One that falls over all the time has once again fallen over. And some are missing — ones I’ve seen in the past and ones I’ve seen pictures of.

I’d like to tell you that they’ve been stolen, but the truth is that they’re just made of local limestone and they fall over and break and get grown over. They get lost.

This is the story of a stone I know existed at one point, but that I’ve never seen in person: that of Lucinda Savage.

The story of Lucinda Savage is convoluted and ridiculous. Much of it has to be untrue, and not untrue in the ways that stories get changed and revised through family lore. I mean “untrue” as in, “Can we say for certain how many Lucinda Savages there actually were?”

What this headstone tells us about the famed sculptor, his family and the lasting impact of slavery

OK, so the Lucinda who had an Edmondson headstone at one point (and may still, but I just haven’t found it) was born Lucinda Jordon in 1888 down in Williamson County, according to her death certificate. This is quite a feat, considering she was already 4 years old when the census taker came by her house in 1880.

About this same time (the 1870s), Lucinda Leach was born in the next county over — Rutherford County. As far as I can tell, this Lucinda, often called Cindy, stayed in Rutherford County, married a guy named Curby (or Kirby) Savage and had a bunch of kids. The only kid relevant to our story is Andrew. Put a pin in him.

OK, flip back to Lucinda Jordan. She disappears from history until 1920, when she’s Lucinda Cohn, divorcee. She has a daughter living with her as well as her grandson Fred. You’d think a Black woman married to a Cohn would stand out in the historical record, but I’m not sure if her last name even was Cohn. In the census, it appears to be “Corn,” which was, apparently, an uncommon but actual last name in Middle Tennessee. Other actual last names in Nashville that might be pronounced like Cohn or Cohen are Cowen and Conn. I never did find a Mr. Cohn with any spelling, so who knows?

Now, back to Lucinda Leach Savage — or rather, her husband Curby, who died in Nashville in 1924. I don’t know where this Lucinda was at this time, but I’m guessing she’s dead, because it appears that Andrew (the kid we put a pin in) put a $500 downpayment on a house for his dad to live in, and there’s no mention of her.

What does this have to do with Lucinda Cohn? Let’s turn to the March 6, 1927, issue of The Tennessean, where we find this sentence: “This was a suit to set up a resulting trust in a house and lot in Nashville, to recover possession of the same from Lucinda Coen [sic], alleged to be the pretended widow of C. B. Savage, deceased, and for a sale of the property.” Andrew sued Lucinda and claimed she was not his dad’s actual widow and therefore should not get his house. Judge Crownover ruled that Lucinda was “the lawful widow of C.B. Savage, and as such was entitled to homestead and dower in the property.”

The thing is, I can’t prove Andrew wrong. I couldn’t find a marriage certificate for them. I can’t even find a death certificate for the first Lucinda Savage. It’s entirely possible that Lucinda Jordan just stepped into Lucinda Leach’s life, and for whatever reason (probably racism), no one believed the one man who would know.

I feel for Andrew. He’s caught up in what feels like the setup to a complicated Nikolai Gogol story. There’s some woman claiming to be Lucinda Savage, but he knows it’s not his mom; he knows he didn’t give his dad or anyone else the money for the downpayment on his dad’s house; and yet the courts are willing to believe that this Lucinda Savage is the Lucinda Savage who was married to his dad. As if Andrew wouldn’t know his own mother!

Andrew died two years later, in 1929, in a car crash. And in 1930, the widow Savage was living in a fairly expensive house on Wharf with her grandson Fred. By 1937, she was dead and buried in Mt. Ararat, under a nice Edmondson headstone.

I think Lucinda’s sister is probably who arranged for her to have an Edmondson headstone. In 1940, William was living at 1434 14th Ave. S. Lucinda’s sister, Johanna Malone, was living at 1400 Wade, which is where 14th and Wade intersect, which was kitty-corner from William.

I keep trying to make my peace with the headstones crumbling and getting lost, telling myself that this fragile local stone breaking apart, becoming unreadable, getting buried, is just what happens. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust. We’re lucky to have had them for as long as we have.

A headstone carved by William Edmondson points to a story many decades in the making

But I also know that, because of these headstones, we’re getting glimpses into the lives of people William knew — mostly ordinary people who just lived and died and were not known outside of their own circles. And I wonder how often we get such a wide-scale glimpse into an artist’s community like this? Or hell, into any community like this?

And I know I’ve said it before, but I can’t stop thinking about it. Every person William carved a headstone for was a survivor, or the children or grandchildren of survivors, of chattel slavery. They were not supposed to be here. Not like this. Not in large, loving family groups. Not in neighborhoods full of people who watched out for them and cared for them, and who they watched out for and cared for in return. And these were people who, by and large, still had very hard lives eking out livings as the labor class for rich white people who barely thought of them as people. They were not supposed to matter. They were supposed to be disregarded and ignored. Most of these folks were not even people who could afford a headstone for their loved ones, hence why they turned to William.

And William literally carved their names in stone. It’s an act of loving defiance so large that it leaves me in awe.

I wish that, as a city, we could figure out a way to honor that act and to save these stones, but it’s probably already too late for some of them, and growing late for others.