As much as I’d like to say that I’ve seen every headstone ever carved by legendary local Black artist William Edmondson, there are still some elaborate headstones visible in pictures of his yard that I haven’t seen in person. They may have never been purchased, in which case, they’re in a landfill somewhere. But there’s still a chance they may be out there.

There’s a story about one in John Michael Vlach’s book By the Work of Their Hands: Studies in Afro-American Folklife. Vlach writes:

When the black quarry workers employed at the Ezell Mill and Stone Company quarry in Newsome Station, Tennessee, came to town with their deliveries of building materials, they would steer past Edmondson’s house on 14th Avenue to drop off the odd-sized stones that the contractor thought unusable. These men were no doubt intrigued with Edmondson’s creative efforts and supported him by augmenting his supplies of limestone. The quarrymen’s goodwill was later underscored when one of their crew was killed in an accident and Edmondson was asked to make a monument for their slain colleague (p. 113).

An immediate problem with this story is that Edmondson started carving in about 1932, and the Ezell quarry was destroyed by fire in 1928 and not rebuilt. Still, maybe he got started earlier than we know? The other immediate problem with this story is that if Edmondson carved a grave marker for a person who lived in or near Newsom’s Station, where is the cemetery they were buried in?

I started scanning the website Find a Grave for Black cemeteries near Newsom’s Station. It went poorly. But this didn’t make any sense. Just to our west, the hills were filled with iron furnaces run by notable Nashville families — the Napiers, the Robertsons, Montgomery Bell and his family, and so on. And those furnaces were staffed with hundreds of Black enslaved people. The actual hard work of rock quarrying (a business a lot of the iron families were also involved in) in antebellum times was done by enslaved people. Their descendants and their institutions — like churches and cemeteries — are usually still around.

I searched death records to see if Black people were buried in Newsom’s Station or, maybe, Pegram at the time Edmondson was working, roughly 1932 to 1951. And yes, dozens upon dozens of Black people who died during that time period were buried somewhere in that general vicinity. I found people buried in the "Newsom Plot," and I found their close family members buried in “Pegram.” I began to surmise that the Newsom Plot was just a family plot in this Pegram cemetery.

I started to talk about this on Twitter, and Janet Timmons — because this is Nashville, yes, this is Janet Timmons from the radio! — contacted me because her boyfriend, Jonathan Roberson, is from Pegram and knows a guy whose relative is the pastor at a church in the area. (Listen, I love you all, but I don’t trust you, so I’m going to be vague about the location of this cemetery. And that means being vague about the church and the pastor, but suffice to say the cemetery is not on any maps I’ve seen. So thanks to Jonathan’s friend for telling us where it is.) And this church just happens to have a large cemetery on the hillside in back of it. We were welcome to go look at it.

So on Sunday, I pulled into the flat area next to the church and began looking at the hillside. There were graves everywhere, many marked by rectangles of what looked to be either leeks or some kind of lily. Many were sunken down, and like they always do, these collapsed graves reminded me of empty cradles. Here is a place of rest for a loved one. There’s a path that goes from the back of the church up the hillside in a big lazy S. It isn't as steep as, say, trying to get up to the Benevolent cemetery on Brick Church Pike, but I still had to stop and rest twice.

The top of the hill was covered in vinca and full of graves, marked and unmarked. We saw what I’ve seen at so many African American cemeteries near here — graves marked by trees, graves marked with distinctively shaped field stones, graves marked with plants covering them, as well as graves marked with stone markers. A few of the graves had the same kind of ferny-looking detail, which I wonder about, whether it’s a lodge designation or just a nice thing to put on a grave. Some of the graves went back into the 1800s, and I’d bet anything that some of the graves marked by trees or field stones go back to the days of slavery.

I have walked up into so many Black cemeteries in Middle Tennessee that I’m really starting to wonder if there’s some meaning to it that I’m missing. Yes, on the one hand, maybe hillsides were spots enslavers didn’t have much use for, so they let them be used for Black cemeteries, and then Black families just kept using them. But a lot of the hillside cemeteries I’ve seen have church yards down at the level of ... well, obviously, the church and the road. But these cemeteries haven’t spread down there. Every time I struggle up these hills, I think of the exertion of people who had to walk up the hill with a loved one in a box between them. These cemeteries aren’t places you can just stumble upon unwittingly. You have to climb up into them. It feels like a ritual movement, especially in this cemetery, winding ever higher. And if God is in heaven and we’re down here on earth, putting your ancestors physically above you sure feels meaningful.

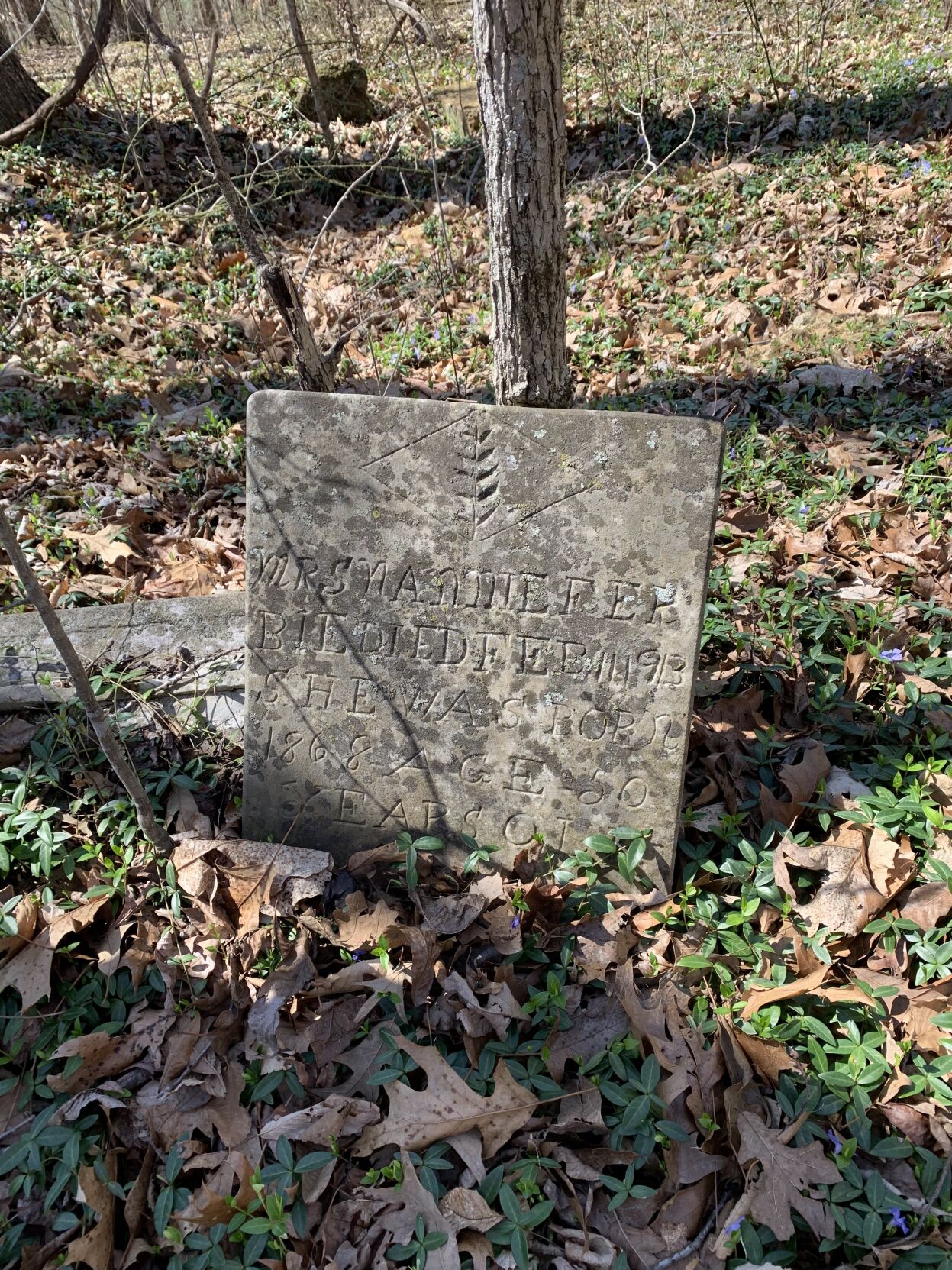

So, it is a cemetery. Is it the cemetery I was seeing in the death records? Well, I knew for sure that Steve Knight is in a Pegram cemetery with his family, thanks to the death records. According to her obituary, his mother-in-law Lottie Mayes was buried in the Mayes Cemetery in Pegram Station. And Lottie’s mother, Nannie Ferby, is at the top of this hill, with a beautiful headstone. This is it, as far as I can tell. This is the Newsom/Hayes/Pegram/whatever cemetery. If a Black person from out here had an Edmondson headstone, this is the likeliest spot where it would be.

Did we find one? No. But a lot of headstones have fallen over and possibly sunken into the ground. I’m not sure that us not finding it means that it’s not there. However, we didn’t see anything with Edmondson's distinctive writing.

But I've just spent the past half-hour squinting at this picture I took of a headstone that seemed blocky in the way Edmondson's headstones can be. Up at the top of the hill, it looked blank. But my camera phone captured a cross. I didn’t get the “holy shit, here’s one!” vibe I’ve gotten in other cemeteries, but I truly wish I’d brought tools to do a headstone rubbing, just to see if I could make out some letters.

Edmondson or not, the cemetery is a special place. After all, the death records I have easy access to are from Nashville, so the dozens of people I was finding lived and worked in Nashville. But when their time came, they wanted to be back on that country hillside, in the company of generations of their families.

And since they were not buried in vaults, they literally stood there with us, in the trees their bodies nourish, a quiet and ongoing family reunion that we got to be a part of for a few minutes.