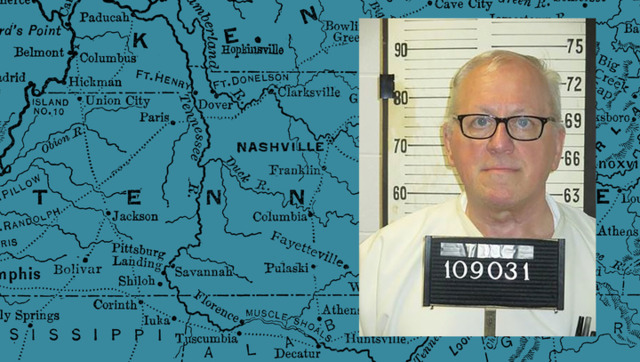

The daylight had not yet expired Thursday night when the Tennessee Department of Correction announced that Don Johnson had been executed for the 1984 murder of his wife. But a darkness had already descended upon the dozens of people who had gathered, yet again, to hold a vigil in a field outside the prison grounds.

There was hope. There is always a persistent hope among the men and women who have spent years and even decades opposing state killings. Even as the 1,496th and 1,497th executions since 1976 took place last night — in Tennessee and Alabama, respectively — they spoke about “the road to abolition.”

But the distraught looks on their faces signaled something grim. With Gov. Bill Lee’s decision to allow this execution to proceed — just months into his first term as governor and with five more scheduled for this year and next — there is now little reason to doubt that Tennessee will continue executing prisoners for the foreseeable future.

Observing Tennessee’s death penalty since it was revived last year has been like taking part in a law school thought experiment, or a demented Dr. Seuss book, about what it would take for a governor to extend mercy to one of the state’s condemned men. Would they stop it for the mentally ill? Would they call it off for the rehabilitated? Are they moved by the undeniably arbitrary nature of death sentences, or a history of horrific childhood abuse? Will the prospect of torture give them pause? Will a story of redemption and forgiveness compel a man whose political identity is built on the sincerity of his Christian faith?

No. No. No and no. No. No. No.

The thought that burdened the men and women gathered in that field Thursday night was this: If Gov. Bill Lee will not grant clemency to Don Johnson, a transformed man by all accounts who had received forgiveness from the daughter of his murdered wife and become a Christian leader on death row, then who would he do it for?

Lee announced on Tuesday that after “after a prayerful and deliberate consideration” he would not intervene to spare Johnson’s life. So, around 7 p.m. Thursday night, officials at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution initiated the twisted liturgy known as the lethal injection protocol. Johnson had been sentenced to death in the electric chair in 1985 for suffocating his wife to death. Years later, the state adopted lethal injection as its primary method of executing prisoners. Johnson could have chosen to die in the chair, as Ed Zagorski and David Miller did last year, but he ultimately waived that right. In doing so, he elected to be killed using a lethal three-drug cocktail that has been the subject of legal fights in multiple states in recent years. It’s the same combination of drugs — midazolam, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride — that one of the nation’s leading anesthesiologists said last year tortured Billy Ray Irick to death. The second drug in the protocol is a paralytic, meaning that even if the prisoner is experiencing every horrifying description of the drugs’ effects — the sensation of being buried alive and then burned from the inside — they would be physically unable to show it.

Associated Press reporter Travis Loller, a media witness to the execution, described Johnson’s final moments:

Don Johnson's last words were a long prayer that in some places echoed the words of Jesus as he was crucified. He asked for forgiveness for those participating in the execution, saying "they know not what they do."He also prayed for "all those I have hurt" and thanked God for God's blessings, including his attorneys and loved ones.

After the lethal injection drugs began flowing, Johnson asked if he could sing. Given permission by the warden, he sang "They'll Know We Are Christians" and then "Soon and Very Soon." His voice trailed off in the middle of the second song after the words, "no more dying there."

Witnesses say Johnson then made snoring or gasping noises for several minutes.

In yet another illustration of the rippling trauma that results from murder, and from executing convicted murderers, Johnson’s family has been split over his fate. While his stepdaughter Cynthia Vaughn was a central figure in his clemency effort, speaking about their reconciliation and how forgiving him freed her from decades of pain and resentment, many others in the family feel differently. They released a joint statement about his execution.

“For the family of Donnie Johnson, this tragedy has come to an end for us all,” read the written statement. “For some, the pain will remain forever. While Donnie Johnson has received a lot of media attention these last few weeks, we hope the victim, Connie Johnson, is never forgotten. Connie was loved and has been missed these many years. Connie had a great laugh and the kindest heart. We pray for peace for her children and for her family. We hope today will give Connie's family some closure they so deeply deserve.”

Some of what we know about Connie Johnson comes from Don, who told Vaughn about her after the two were reconciled. She loved The Rolling Stones, romantic comedies and country cooking. She wore Chanel No. 5.

Out in the field, as they awaited word from the prison, the group that included regular death row visitors, clergy members and other activists stood in a circle to pray. They prayed for Connie and her family. They prayed for Don. They prayed for Gov. Bill Lee. And they prayed for the men and women tasked with putting a man to death.

Al Andrews, a regular death row visitor, also asked that the group pray for a lone man on the other side of the fence at Riverbend that separates death penalty opponents from death penalty supporters. Andrews confessed he’d hated that man, who is reliably present to cheer on the executions. But on this night, Andrews said with emotion welling in his voice, he just felt sadness and compassion for the man — and if Andrews hated him, Andrews was no better than him or than the state that was executing Don Johnson.

“He seems so alone,” Andrews told me later.

Later, the group took communion.

Don Johnson's supporters partake in communion outside Riverbend Maximum Security Institution Thursday night

And in honor of one of Johnson’s final wishes — that in lieu of his own special last meal, supporters feed the homeless — they took up a collection to buy pizza for the men and women who live on Nashville’s streets. Later Thursday night, outreach workers with the homeless advocacy group Open Table Nashville delivered the meals.

“When I told one man where the pizzas were from, he said ‘no way’ in disbelief and then took off his hat in reverence,” Open Table’s Lindsey Krinks tells the Scene. “Felt like our third communion of the night.”

Other supporters of Don’s who had gathered for a vigil at Riverside Seventh Day Adventist Church in Nashville where Don was an ordained elder also collected Kroger gift cards. The church will purchase food to distribute to homeless Nashvillians next weekend.

The cycle seems certain to repeat itself. Stephen West is the next man scheduled to die, on Aug. 15. But last night in Tennessee, the contagion of trauma and pain that characterizes the death penalty met with something else, a defiant breaking of bread. And in his own voice, Don Johnson replaced the executioner’s song with a hymn:

No more dying there.

No more dying there.

No more dying there.