One question that has been nagging me for years is why white people didn’t kill Leander Woods back in the day. I wrote about Woods for The Washington Post many years ago, if you want to dive further into his extraordinary life. But to make a long story short, he and his buddies appear to have dislodged the Ku Klux Klan from Fort Negley and taken over the fort. He then spent the next 30 years of his life annoying the shit out of white Nashville by preaching and getting drunk and stealing chickens and cavorting with young women he claimed were his nieces. In newspaper articles about him, he comes across like the human equivalent of Bugs Bunny, just able to slip out of trouble and leave the people after him looking foolish.

This was a reckless way for a Black man to live in the latter half of the 19th century — or as is possible in Leander’s case, to just have a reputation for living that way was dangerous. And yet live he did, until he was an old man.

This has always baffled me. Leander Woods lived in South Nashville, basically kitty-corner from Napier School. When he managed to talk a church into giving him the pulpit, it wasn’t secret. And he was regularly drunk with pretty women. Leander was a man who was utterly and easily findable. And this was a town full of racists whose egos bruised easily. Why didn’t a lynch mob go after Woods? I’m glad it didn’t happen, but I’m also surprised.

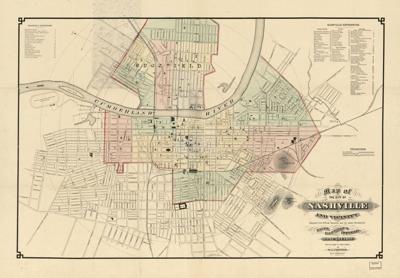

Or I was surprised until recently, when I learned about Sladetown. Sladetown, originally called “Varmint Town,” stretched from roughly Peabody (I’m guessing based on Captain Ryman having lived in Sladetown) to Brown’s Creek between Lafayette and the river. So if you were at the wharf and started heading east, it was Black Bottom, Sladetown and then Jim Town. Jim Town had its downtown, such as it was, including a post office where Purity Dairy is now. Sladetown was considered the worst neighborhood in Nashville — dirty, dangerous and full of vice, and Leander Woods was right in the center of it.

But he wasn’t even the most interesting — or troublesome — resident of Sladetown. That honor belongs to the roving gangs of violent women who terrorized the neighborhood for years.

It all started about this time of year — on Aug. 19, 1883 — at the camp meeting at Trimble Springs Bottom. The white reporter who wrote about the story for the Daily American managed to give a pretty good description of the area where the camp meeting was. He says that the “rock-enclosed spring [was] lying under the shade of two beautiful trees.”

The free woman of color ran an ice cream saloon downtown between 1830 and 1860

“In the rear of the spring was the enclosure where the camp meeting has been held," he wrote. "The ‘tent’ as it is called, is a long shed formed by uprights, with boards nailed over the top and along the sides shut in by strips of old carpet and odds and ends of cloth.”

That Sunday, white people had shown up at the evening service to gawk at worshippers. (Weirdly enough, this pissed off the Nashville Banner, and they wrote all about how people disrupting church were the worst, which, coming from the Banner of that era, is shocking. The Banner taking the side of Black Nashvillians while The Tennessean's precursor came to also gawk and write racist stories? Was it topsy-turvy week?) A riot broke out.

From the Aug. 21, 1883, American story, after an altercation near the spring, “Some white man then shot into the congregation, which created a general stampede, the negro women running in every direction; but the colored men turned upon all the white men present and commenced rocking them and beating them with sticks and whatever they could lay their hands on.”

This, then, appears to be the last time any woman in South Nashville would appear in public without a weapon. There are about to be a lot of names, but the two women you need to keep your eye on are Missouri Hockett and Emma Boyd. Everyone else, you can just let their names wash over you.

So the first incident took place on Sunday, Sept. 2, 1888, when Missouri Hockett was arrested for assaulting someone with rocks. We don’t know who. Then on Wednesday of that same week, Emma Boyd was at church, at Seay’s Chapel, when she assaulted Willie Purlsey. The Banner article about the attack says, “The origin of the difficulty exists in the rivalry of Emma Boyd and Willie Pursley, two girls who attend the church, for the affection of a dusky dude.” You can tell the reporter at the Banner wasn’t working super hard on getting the facts of the story right, because Willie Pursley was a dude, and at the start of the story, the incident took place on Wednesday, but by the middle of it, the incident took place on Sunday — meaning Missouri Hockett’s rock assault may have been tied in with the mess I’m about to recount.

So Emma Boyd and Willie Pursley and Willie Pursley’s mom get into a huge physical fight in church. They get sent out into the churchyard. Becky Clark comes out into the churchyard brandishing a whip, which she’s carrying because some girl whipped her earlier, and Becky’s armed for revenge. But as Becky’s trying to get out of the church, “Trustee Wood” (who I hope with all my heart is Leander Woods) steps on her foot. This causes the ruckus to raise quite a bit. Emma and Willie are fighting. Emma bites Willie’s finger, Willie hits her, Willie’s mom takes Becky’s whip and is trying to whip Emma. It’s a mess. Everyone gets arrested.

The next spring, Emma pops back up when she’s arrested on four counts of larceny. And then we get to May 1889. Missouri Hockett and Mary Logue get charged with disorderly conduct one week. The next week, Missouri is fined for using profane language. The first week of June, Missouri and her mom Ann fight Callie Blair and Dinnie Black. Fighting and profane language continue throughout June.

July 23, there’s a big dance in Sladetown, and Effie McClendon, Missouri Hockett, Lizzie Jackson, Sue Crawford, Lucy Crawford and Emma Boyd all get in a huge row. Women are throwing rocks at each other. Smashing bricks on each other. And the next night, Emma Boyd fights Sue and Lucy Crawford again. Missouri Hockett fights Emma Jackson (I think this is actually Lizzie Jackson). So two nights of women just rocking the shit out of each other.

Sherrod Bryant was a free person of color and probably the richest Black man in Davidson County during his lifetime

So the men of Sladetown — white and Black alike — decide to put a curfew in place and to take turns patrolling the streets to make sure that all the women are at home and not shoving each other onto the train tracks or something. Which I guess is a useful bit of information to have — if you want men to find some semblance of racial harmony, women need to be really scary.

These women are all in and out of jail for fighting each other. And then right before Christmas, Emma Boyd and two other people beat Missouri Hockett to a bloody pulp. But somehow Missouri ends up going to jail for assaulting Emma Boyd. Emma Boyd continues to be a terror. She’s setting fire to people’s houses and stealing from them and continuing to hit people with objects. Finally, in 1900, she appears to go to prison.

A short time later, in 1902, Mandy Floyd dies. The Sisters of the Mysterious Ten approach the pastor at Seay’s Chapel about getting into Mandy’s house to make it ready to receive her body.

Wait. The Sisters of the Mysterious Ten? Mysterious Ten whats? How is this not a band already? I was imagining some kind of witches’ coven of long-robed women all chanting around Mandy’s house, but it was just the women’s branch of the United Brothers of Friendship. Far be it from me to tell anyone how to run their secret society, but if you’re naming shit and someone comes up with “Sisters of the Mysterious Ten,” you let her take a crack at naming the men’s group too. Could you imagine being in the United Brothers of Friendship, which sounds like a group of guys who eat ice cream after playing pickleball, while your wife is a member of a group that sounds like they watch all the scary parts of Fantasia as a warmup for their evenings of occult activities? Sladetown — where the women are just scary.

Why are we side-tracking on Mandy Floyd anyway? Because her sister is Missouri Hockett, and when she shows back up in town, she accuses the pastor, the Rev. William Elliston, of having stolen Mandy’s stuff while she lay there dead. She has him arrested. Rev. Elliston, I feel bad, but thank goodness she didn’t hit you with a rock. I guess she mellowed out in her old age.

There’s so much more, and every bit of it is like this. So much fighting. Women bringing bricks and rocks to church in case anything breaks out there. The area has one police officer, and it quickly becomes a joke that he’ll only go into the neighborhood in broad daylight when other men are present. And I’m leaving out all the murders that come later that William Edmondson got caught up in the tail end of.

A couple of groups of women terrorized a whole neighborhood for decades! Mothers and daughters fighting side by side. Grudges getting carried down to granddaughters. And why? Honestly, I have no idea. The papers keep saying they were fighting over a man, but as hard as I find it to believe that women could dominate a neighborhood for two generations and then the story be forgotten — even though that’s seemingly what happened — I simply cannot believe this. If there were a man in Nashville who provided such miraculous dick that crowds of women would beat each other over him for years, wouldn’t we know his name now? Missouri Hockett attacked her first person in 1888. Emma Boyd killed her last victim in 1911.

Zora Neale Hurston moved into that neighborhood in 1912. If this man existed, she would have written something about him at some point, I’d think. He’d be a local celebrity. I mean, Timothy Demonbreun had two wives for a handful of years and we’ve never stopped hearing about him. A man who can dickmatize a whole neighborhood for two decades? Such a legend wouldn’t be lost. I hope, anyway.

No, this has to have been about something else. But what? I don’t know.