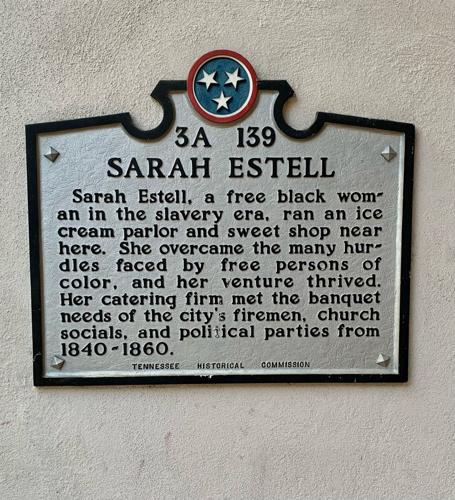

I’ve long been fascinated and confused by Nashville’s original ice cream empresario (empresaria?), Sarah Estell. A free woman of color, she ran an ice cream saloon downtown for many years and was a well-regarded caterer. If you’re the descendant of any Masons who ate at the Grand Lodge between 1830 and 1860, you owe some of your robust epigenetics to Sarah, who was constantly feeding them at events. But what confused me is that Sarah Estell was making ice cream before the invention and dissemination of the ice cream churn — meaning she had access to specialized, expensive tools. And she had access to ice in the summertime in Nashville, before air conditioning. It would be very difficult for any woman to get her hands on the kinds of start-up funds Sarah had, and it just seemed to me impossible for a Black woman to have access to that kind of money at that time.

There had to be some kind of explanation. That explanation was staring me in the face a decade ago when I first wrote about her. I literally typed the explanation and didn’t know it:

In 1833, during the big revival at McKendree Methodist Church, little Jimmie Dick Hill got other boys to the altar by bribing them with Miss Sarah's ice cream. In her book Old Days in Nashville, Tennessee, Jane Thomas writes, "Between the song and the prayer he would take the boys to Sarah Estell's and treat them to ice-cream, and then take them back to church and go to singing and praying again." I think we can all agree that long church services still could be improved by an ice cream break.

For 10 years I’ve been mulling over Sarah. Who was bankrolling her? Whatever happened to her?

If all you knew about Nashville was from the glowing national press we've been getting lately, you might get the impression that black Nashvil…

And then, just the other day, I stumbled across this post from another Sarah at Metro Archives. (Side note: I don’t know who this Sarah is, but every time I find an interesting history post on the library's site, I’m always like “I bet this is Sarah,” and it always is! Who are you, Sarah, and how are you so awesome?) History Sarah just casually drops this little nugget in her list of notable people buried at the city cemetery: “Polly Hill (1847): Mother of former Nashville caterer, Sarah Estell.” I’m sorry. What? All along we knew who Sarah’s mom was?

OK, so I went in search of more information about Polly Hill, and there she is on the city cemetery website: “Polly, slave of H. R. W. Hill, Dec 11, 1847, age 61.” And here’s where I throw all my papers into the air in disgust. Of course. Of course.

I’m going to try to cram a lifetime of ridiculousness into a paragraph, but here’s the brief on Harry R.W. Hill. One day, Harry has to go to the state legislature and say, “Look at this beautiful enslaved boy child here with me. Oh, his straight hair and his beautiful blue eyes. Please let me free him so that I can send him to Ohio to school. His name is Pleasant. No, he’s not my son. What are you even saying?” Then Harry is like, “Oops, I’m dead. Here’s my will. Please make sure Pleasant is able to keep the huge estate down in Louisiana I left him. That I left him for no reason. I assure you. I just like leaving random children huge estates. Also to Pleasant’s mom, Violet, I’m leaving $600 a year for the rest of her life, because ... um ... Oh! Right. She was such a good nurse to my dead wife before she died. Am I leaving anyone out? Oh, yes. I do have a son. James Dick Hill. [Yes, the little Jimmie Dick Hill getting ice cream for all his church bros in the Sarah Estell story!] Give him a lot of money, too. Please make sure this happens, my dear friends, once-and-future Nashville Mayor John Bass and John “Let’s Forget About All the Slave Trading and Focus on My Luxurious Resort and the University I’m Funding” Armfield.

Y’all, I cannot even begin to tell you how much money is represented in that last paragraph. Hill had more money than God. At the height of his slave trading, Armfield (and his partner, Isaac Franklin) were two of the wealthiest men in the nation, and John Bass was once like, “Oh, Nashville. Are you running out of money? No worries. You can just use my money to operate until you’re back on your feet.” This is the kind of money that can warp reality and allow someone like Sarah Estell to have the life she had.

In real life, could an enslaved woman in Nashville have a child who lived in Nashville who was free? No. In Hill’s world? Sure. In real life, could a free woman of color get access to enough ice in the summer to own a whole-ass ice cream shop in the 1830s? No. But in Hill’s world? Little Jimmie Dick needed ice cream during church, so perhaps Hill warped reality to make it happen. Was Sarah also Hill’s kid? Who can say? I wouldn’t be surprised, though.

Here's another bit of something interesting. In 1860, Sarah Estell owned a man her own age. In 1850, she was living with a man, Frank McEwen, also her own age. Now that I’ve seen so many Black Nashvillians owning family members, I wondered if Frank was the same guy Sarah owned. But enslaved people aren’t named in the census, right? And when they are, isn’t it normally that we see them on the slave census in 1850 and then named in 1860? Frank would be working opposite.

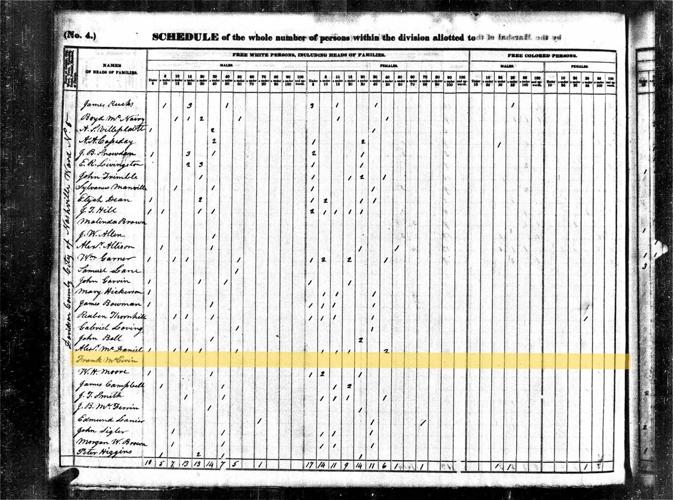

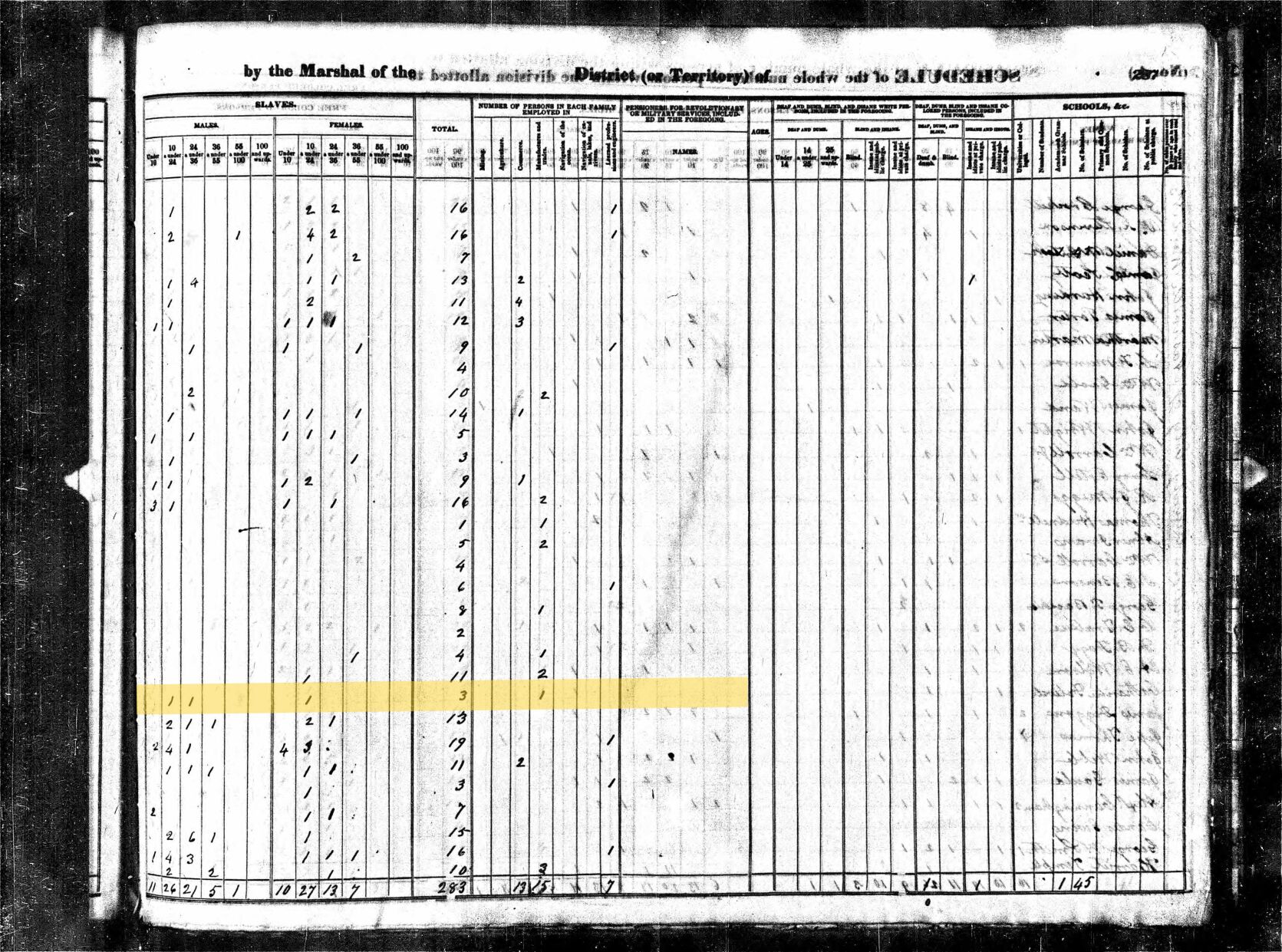

But, y’all, I found Frank in the 1840 census. And I hardly know what I’m looking at. You see his name, and then there’s not a single free person marked. You have to go over to the next page, and Frank’s household is made up entirely of three enslaved people — Frank being one.

A page from the 1840 Nashville census showing Frank McEwen (part one)

A page from the 1840 Nashville Census showing Frank McEwen (part two)

I always thought enslaved people were counted in the households of their enslavers. I had no idea you could find named enslaved people in the 1840 census. But I did a quick count of the 1840 Nashville census and found 35 named enslaved heads of households. There were only 2,114 enslaved people in Nashville in 1840, and there, in the 1840 census, are the names of 1 percent of them: Rutha Chandler, Malinda Brown, Frank McEwen, Jacob Williams, Anderson Casseday, Robert Woods, Hannah Criddle, Patsy Lanier, Landon Bryant (maybe, he's got a smudge), Maria Marshall, Catherine Campbell (another maybe) Maria Hagan, Malinda Brown, Candes (or Landes) Ewing, Harriet Cantrell, Harry Grimes, Lewis Garrett, Preston Leake, Celess Rayborn, Lucy Burton, Frank Endsley, Rachel Kelly, Jacob Wells, Nancy Harding, D. Hodge, Julia Rutledge, A.W. Vanleer, Lotty Beshears, Ephraim Martin, Francis Campbell, Lucy Cowls, Lucy Woods, Sally Thomas, Fanny Hays and Adeline McNairy.

I haven’t studied this, but I did spot-check to try to understand what was going on. Take Rutha Chandler. I’m assuming Rutha is a female name, but if so, we have strangeness beyond just enslaved people as heads of households. Because Rutha’s household included three adult women and four adult men. By any common understanding of how society saw households in the 1840s, the head of this household should be a man. But maybe our understanding is wrong.

Anyway, this is my favorite thing about history. You solve one mystery and it reveals a bunch more.

Here’s my guess, though. We know there were a lot of people in Nashville who were enslaved by people who lived out in the countryside. We can look at the last names of these people and — I mean, just what I know off those top of my head — you find Chandlers out in Hermitage, Laniers up near Sumner County, Ewings up in Bordeaux, Hardings out in Belle Meade, Vanleers out at the iron mines. So these people could have valuable skills that could benefit from a larger consumer base. If you’re a tinsmith, for instance — this is an incredibly useful skillset to have on a farm, but now you’re a skilled artisan and there’s not that much work to keep you busy. The person holding you prisoner could throw you out in the field, but he could also send you into town, where there are enough people who need your skills to keep you busy, and as long as you sent money back to the farm and returned to the farm when you were needed, you live in Nashville. You’re worth more as a busy tinsmith than you are as a field laborer, so you go to where you’ll stay busy making more money for your captor.

But the census is supposed to provide information on who is living where, it is supposed to count enslaved people (for the purposes of assigning U.S. representatives), and it needs to associate that information with a name — the head of the household. Our tinsmith lives in Nashville, and he needs to be counted. The census taker could hope that the enslaver out in the countryside reports that he has the correct number of enslaved people in his household, even the tinsmith, but isn’t it safer to just enumerate the tinsmith and his household here?

This complication, brought about by the many strange ways Nashville enslaved people, ends up — nearly 200 years later — providing us with identities of some of the people who were not supposed to have official, legal identities as anything else other than property. That’s really cool.