If all you knew about Nashville was from the glowing national press we've been getting lately, you might get the impression that black Nashvillians contributed only sit-ins and hot chicken to the city's development.

"It's a bit discouraging to see the city's diversity, especially its black population, overlooked," says Nichole Perkins, a local writer who has contributed to Think Progress and other online publications. "The nickname 'Music City' doesn't originate with country music but from the admiration Queen Victoria held for the Fisk Jubilee Singers.

"It would be nice to see some acknowledgment of the city's four historically black colleges and universities, or that one of the country's remaining black-owned and -operated bookstores — Alkebu-Lan Images — is here, or even the fact that the black population is almost 30 percent of the city. We're here, and we're just as important to Nashville's growth as anyone else."

Genma Holmes, host of the radio show Living Your Best Life With Genma Holmes on WENO-760 AM The Gospel, agrees that we're missing out on a lot of important local history. "Every time I hear something negative about the black community," Holmes says, "I have a story from Nashville that proves them wrong."

Even after the advances of the civil rights era, the history of slavery and Jim Crow remains a bitter pill for boosters to swallow. That is changing. At the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Nashville, we honored the brave sacrifices of the U.S. Colored Troops who fought here. Where white Nashvillians once rained blows and abuse on civil rights activists, civic leaders have taken modest steps toward recognizing the debt owed those who helped bring about a more just city and country.

Names such as William Edmondson, DeFord Bailey and Ted Jarrett are getting their due in the city's roster of cultural contributors. The Fisk Jubilee Singers are celebrated as musical ambassadors to the world, and we love to tell visitors how Jefferson Street helped shape Jimi Hendrix into the rock god he became — even if city and state fathers kneecapped that thriving district in the 1960s.

But that's only a start. From the city's founding, black residents found ways to shape Nashville into a place where they could live lives beyond what the white power structure allowed. Here are some stories that only hint at the richness of the city's shared history — a subject whose scope deserves commemoration, and investigation, long after Black History Month.

Black Bobb Renfroe, owner of Old Hickory's favorite tavern

Bobb Renfroe’s emancipation papers

Black Bobb Renfroe, whose name is spelled different ways in different documents, is famous for two things: running Nashville's first hit restaurant, and having Andrew Jackson as some kind of weird guardian angel.

Renfroe arrived in Nashville the same way many early settlers did — fleeing from American Indians who had massacred most of his household. He was the slave of Joseph and Olive Renfroe, who brought him when they came to Middle Tennessee with the Donelson Party. The Renfroes first settled along the Red River, but two devastating Indian attacks later, Olive and Bobb were the only Renfroes left. They made their way to the safety of Fort Nashborough, where Olive sold Bobb to Josiah Love. As it turns out, Love's attorney was one Andrew Jackson.

Love had some difficulties with money and booze. After some encouragement from Jackson, he sold Bobb to Robert Searcy, a lawyer in town. In 1794, the Davidson County Court issued a ruling that "a certain Negro called Bobb in the town of Nashville be permitted to sell Liquor and Victuals." Bobb opened a tavern. In 1800, Anderson Lavender, a white man, assaulted the tavern owner, which could have put an end to his career.

Shockingly, given the times, Lavender was indicted, even though Bobb was a slave. Andrew Jackson was among the judges who heard the suit. Since Bobb's tavern was a favorite of local attorneys — including Jackson — it made so much money that he was ultimately able to buy his freedom from Searcy. In 1805 Bobb sued one Charles Dickinson. The next year, Jackson killed Dickinson in a duel.

Bobb later served under Jackson in the Creek War of 1813-14. Bobb Renfroe remained a prominent tavern owner until 1816, when he disappeared from the public record.

Bobb Renfroe, Christopher Christian, Caesar Prince, Philip Thomas and Jeffery Locklier were all black Nashvillians who served under Jackson in the Creek Wars.

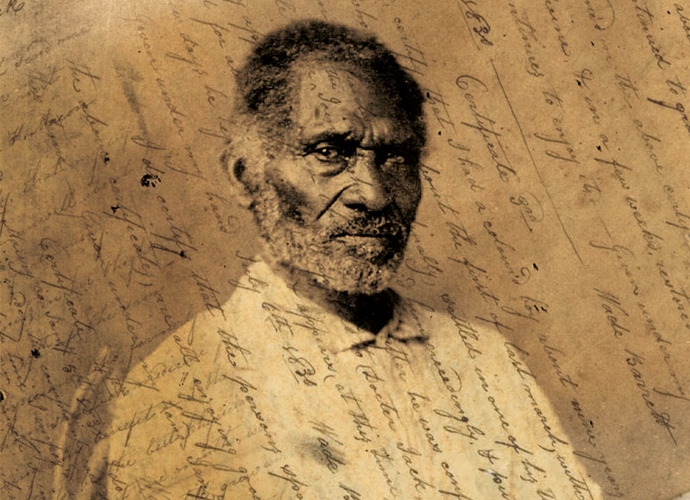

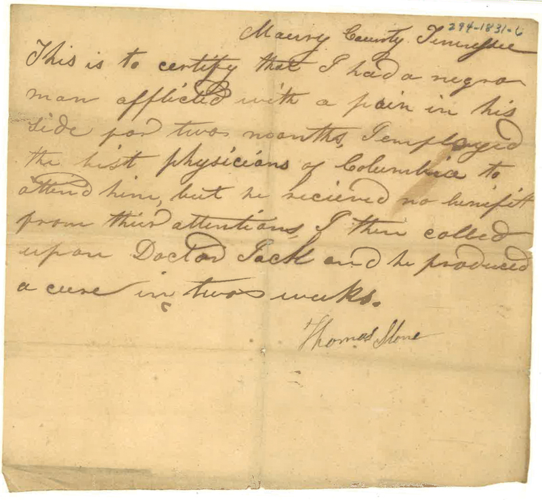

Jack Macon, the doctor who challenged the law

Part of a petition for Jack Macon to practice medicine

The remarkable Jack Macon was owned by Maury County resident William H. Macon — the nephew of early North Carolina Sen. Nathaniel Macon, for whom all towns, cities and counties called Macon are named. Like his uncle, William seemed less than enthusiastic about the government trying to tell him how to run his life. So when Jack showed a propensity for healing the sick and the lame, William sent him out to take on some white patients, even though it was illegal for slaves to practice medicine. He amassed a loyal clientele.

Since Jack wasn't legally a person, when he was busted, William got in trouble. In 1831, Dr. Jack's patients petitioned the state government to find a way to let him practice medicine without breaking the law. The state legislature declined. William and Jack moved clear across the state to Fayette County, where Jack continued to practice medicine illegally. In 1843, his white patients again petitioned the state legislature to give Dr. Jack an exemption to the law. This too failed.

Ten years later, Jack Macon was listed in the first Nashville city directory among the other doctors — "Jack, Root Doctor, Office — 20 N Front St." Since he has no last name, we can surmise that he's still a slave — a slave illegally practicing medicine in the open, mere blocks from the legislature that refused to let him practice legally. For whatever reason, no one in Nashville troubled him about it. There's no record of him being freed, but interment records at the Nashville City Cemetery state that Jack died a free man of color, "known as Dr. Jack," on May 16, 1860, at the age of 80.

Sarah Estell, Nashville's early pied piper of ice cream

From at least the early 1830s through 1860 — records before and after that are sketchy, for obvious reasons — Sarah Estell sold ice cream to Nashvillians. In 1833, during the big revival at McKendree Methodist Church, little Jimmie Dick Hill got other boys to the altar by bribing them with Miss Sarah's ice cream. In her book Old Days in Nashville, Tennessee, Jane Thomas writes, "Between the song and the prayer he would take the boys to Sarah Estell's and treat them to ice-cream, and then take them back to church and go to singing and praying again." I think we can all agree that long church services still could be improved by an ice cream break.

Estell expanded her business, and by 1859 she was running a boarding house and catering service at 89 North Cherry (now Fourth Avenue) that served, naturally, ice cream. Her catering service supplied food to churches, firemen and politicians. But there's an interesting fact hidden here in plain sight — Sarah was extremely well off. Ice cream in the 1830s was fancy, a delicacy reserved for statesmen, politicians and other blue-bloods who could afford it. Leaving aside the start-up costs associated with the equipment she needed, which was expensive and hard to come by in those days, Sarah Estell could afford a steady supply of ice. In Nashville. In the days before electricity.

At the start of her ice-cream making career, Sarah Estell was most likely making a custard-based ice cream — dairy, eggs and sugar slightly cooked before chilling. Since she was making ice cream before the advent of the hand-crank, she would have ended up with a thick, not very airy ice cream, most likely flavored with chocolate and various fruits. Parmesan ice cream and rye bread ice cream were also popular.

Alfred, a bad example of a 'good' slave

Alfred

A persistent myth of Southern history is that of the slave who was happy because of his enslavement. There are thus two historic versions of Alfred, Andrew Jackson's most trusted slave. The white fantasy version of Alfred is often cited as an example of a "good" slave — loyal, industrious, bright, trustworthy, loving to his owners. He practically ran the Hermitage and took care of the property until his death. When people try to argue that slavery wasn't all bad, that version of Alfred is the kind of slave they point to as someone who thrived in the institution.

In real life Alfred was gravely unhappy. In his memoir, the Jackson family tutor, Roeliff Brinkerhoff, says Alfred "thirsted for freedom." Brinkerhoff recounts how he once found Alfred in an alarming state of depression. Brinkerhoff tried pointing out how sweet Alfred had it — why, he had a kind master, a pleasant home, the respect of his peers and his owner, and no question about his lot in life.

"Alfred did not seem disposed to argue the question with me, or to combat my logic," Brinkerhoff writes, "but he quietly looked up into my face and popped this question at me, 'How would you like to be a slave?' "

Whenever people try to argue that slaves didn't have it so bad, let Alfred have the last word.

Hannah, the gatekeeper of Andrew Jackson's legacy

Hannah and her husband Aaron

At the same time white folks were telling themselves a story about Alfred that they liked better than the truth, another of Jackson's slaves, Hannah, was telling America a story about Jackson that she liked better than the truth. Jackson's personal papers leave a portrait of a rather ordinary slave owner, quite capable of the brutality associated with the position. He regularly ordered the whippings of his slaves, male and female.

But to hear Hannah tell it, Jackson was a font of kindness. According to her, he "was more a father to us than a master."

Hannah's willingness to tell a story of Jackson more complicated than "he never met a man he didn't eventually shoot at" made her a popular primary source. So did her closeness to him — she regularly brushed his hair while he told her stories of his life, many of which made it into the historical record. The Cincinnati Commercial, in 1880, and the Nashville Daily American, in 1894, both ran extensive interviews with her about life with Andrew Jackson.

But even before that, in 1859, Jackson's first serious biographer James Parton interviewed Hannah. Scholars think that many of the episodes we know about Jackson's childhood — how he was struck in the head with a British sword, how he had to walk home from a prison camp because his even sicker brother needed the horse, even his relationship with his mother — come to us through stories Hannah told Parton.

Even now, a lot of what we know about Jackson comes to us through Hannah's interpretation. According to Cumberland University history professor Mark Cheathem, an Andrew Jackson scholar, "Hannah was present at both Rachel and Andrew Jackson's deaths. Her memory of those two events, as well as her descriptions of Jackson's paternalism, continues to influence the way that we view the General."

Nashville's first black schools, where burning was fundamental

If a hallmark of the civil rights movement was an organized willingness to break the law to improve the lives of black people, then Nashville's started in 1833, when Alphonso Sumner started the first black school in Nashville. In retaliation, angry whites closed Sumner's school and publicly whipped him in 1836, and he fled to Cincinnati.

Black families were determined to educate their children, though, and a few years later they paid a white man, John Yardley, to teach their children. He left the position after a year, and his assistant Daniel Wadkins, a black man, took over. Wadkins was not universally loved by his students. According to writings at the time, he was strict, conservative in his beliefs about racial equality and somewhat disorganized, and he moved the school's location frequently. But perhaps he felt that teaching approach would shield him from the attention of angry whites.

On that score, he seems to have been successful enough to inspire others to start their own schools. Even the Catholic diocese opened a "Sunday School" for black Nashvillians, where adults learned to read and write while attending class on Sundays. Black schools in Nashville had a good run for well over a decade, but white vigilantes closed Wadkins' school at the end of 1856 and forcibly closed another school in 1858, ending formal schooling for black people in the city until the Civil War.

Some reports from the time say these white vigilantes burned the schools. Others make it sound like the vigilantes just yelled threats at the teachers and students. Nevertheless, if you were writing a history of black education in Nashville, you could devote a whole chapter to mysterious fires at black schools and the white folks with matches standing nearby who, no sir, most definitely not us, had nothing to do with the blaze. Considering that the events at those two schools were frightening enough to end black education across the board when publicly whipping a teacher couldn't, the smart money is on the fires.

1850 — More than 80 percent of free black children, and half of the free black adults, in Nashville could read and write. Many enslaved children, who were illegally educated in these same schools, could also read and write.

Nashville's Underground Railroad: One of the official reasons Alphonso Sumner was whipped in 1836 was for sending letters to a slave from Nashville who had escaped to the North (thus showing that the schoolmaster knew exactly where the fugitive slave was, and implying he had helped him get there). Almost all of Nashville's antebellum black residents had ties to enslaved people. Free black people often married slaves; free people had parents, siblings, children or friends who were slaves; slaves were sometimes freed (or, as with Dr. Jack Macon, so unsupervised by his owner that he was practically free).

At the same time, any black person in Nashville, free or not, was in danger of being sold against his or her will. You'll often hear people these days say that Nashville didn't have an underground railroad — and even if it did, we just don't have any way of knowing who was involved. But any study of Nashville's black history before the Civil War makes it clear that the Underground Railroad ran through its black neighborhoods. Black residents were helping others escape to freedom.

Haunted by a history we've forgotten — Roger Williams University and Tennessee Central College

Nashville is currently home to four historically black colleges and universities — Tennessee State University, Fisk University, Meharry Medical College and American Baptist College. We live among the ghosts of two others.

Roger Williams University was a Baptist college that stood where the Peabody College at Vanderbilt now stands. Roger Williams taught its students a wide range of scholarly subjects and trades, but it was primarily focused on the education of preachers. As that part of town became more affluent and white, Roger Williams began to have more and more mysterious problems. After a rash of bullets flying through windows and two devastating fires, the college sold its land to Peabody Normal College, which was looking for a new home. Roger Williams University survived for a couple of more decades on Whites Creek Pike, but eventually it became part of LeMoyne-Owen College in Memphis. The American Baptist College and the World Baptist Center sit on the Bordeaux campus currently.

Tennessee Central College, later Walden College, was a Methodist college just off Lafayette Street founded in 1865. (Cameron College Prep sits today on the old campus.) In 1876, the college opened the first medical school in the South for African-Americans — the origins of Meharry Medical College. Tennessee Central also trained lawyers, pharmacists, dentist and nurses. Alas, Tennessee Central was in many ways a victim of TSU's success. In 1922, to save money, it moved to the site off Murfreesboro Road where Trevecca Nazarene University sits today. A few short years later, it folded.

Bob Hurston, the brother of Their Eyes Were Watching God novelist and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, lived on Lafayette and attended Meharry. In the early 1910s, Zora Neale lived with him and his family there on Lafayette.

Mary Magdalena Tate, the woman who founded a church and became its bishop

Mary Magdalena Tate was, as far as anyone can tell, the first woman to organize a worldwide church and to rise to the rank of bishop in it. In 1903, she founded a religious organization eventually known as the Church of the Living God, the Pillar and Ground of the Truth Inc., headquartered in Nashville. She travelled around the South preaching and organizing her followers, nicknamed the "Do Rights," into congregations. Pentecostal churches allowed women into leadership positions for a brief period in the early 20th century, but most reverted to male leadership after a decade or so.

Not so with Mother Tate's church. She saw her life and her ministry as directly affecting the debate about the roles of women and black people in America at the time, and she took deliberate steps to make sure that ministry opportunities for women stayed open and available. Some of her fierce commitment to social justice can still be seen when you drive by the church at the corner of D.B. Todd Jr. Boulevard and Heiman Street — the Mississippi state flag, with its Confederate emblem, always flies upside down.

The Streetcar Boycotts, the lost battle that showed how to win the war

In 1905, the General Assembly segregated all public transportation in Tennessee. Black people across the state immediately launched protests, and the longest and most successful one was here in Nashville. The Clarion newspaper urged black Nashvillians to "trim their corns, darn their socks, wear solid shoes and walk."

The boycott was immediately successful enough that whites began to complain that black leaders were "agitators" stirring up black residents — a whine that would be heard time and again throughout the civil rights era. Publisher R.H. Boyd, lawyer James C. Napier and funeral-home director Preston Taylor took the fight even further. They started a rival black-owned public transit system, the Union Transportation Co. In revenge, the city of Nashville enacted a tax on their electric streetcars. Whites also vandalized the streetcars while they were charging, and white vigilantes sometimes attacked the boycotters.

The boycott ended after some months with mixed results. Black Nashvillians clearly demonstrated their economic muscle. But the white power structure demonstrated that it was willing to withstand financial blows to preserve the status quo of racial injustice. The streetcars remained segregated.

Nevertheless, what often seems like a failure in the moment can be a seed for future successes. Civil rights activists in the 1950s and '60s were strongly influenced by the earlier Nashville boycott. They would apply its precepts with much greater success.

The good works of the three John Works

John Work’s house

As Nichole Perkins noted earlier in this story, the origins of the nickname "Music City" reside with the Fisk Jubilee Singers. But three Nashvillians whose roots go back to the days of slavery helped the city stake its claim to the name — and all three were named John Work.

The first John Work was born into slavery in Kentucky in 1848. He was purchased by a Col. Work here in Nashville, who took John with him to New Orleans. There John attended rehearsals of the opera company and developed his singing voice. When John Work returned to Nashville before the Civil War, he organized and trained an African-American choir at the First Baptist Church. Three of his choir members were future Fisk Jubilee Singers.

His son, John Wesley Work Jr., taught at Fisk University and reorganized and revitalized the Fisk Jubilee Singers. John Jr. collected black spirituals and was the first person to publish "Go Tell It on the Mountain," as he considered spirituals to be vital and vibrant ways of sharing the faith and wisdom of the ancestors. Not everyone shared his opinion. In the post-Reconstruction era, many African-Americans didn't want to be reminded of slavery in any way, and the tendency of white minstrel shows to mock black folk music — especially spirituals — led many black people to distance themselves from the form. Work left Fisk under somewhat unclear circumstances, possibly linked to his love of this "embarrassing" old music.

Still, the feelings between Fisk and the Works family couldn't have been that hard, as John Work III began teaching there in the 1930s. This John Work continued the legacy of his father and grandfather, and he too collected African-American folksongs and spirituals. He directed the Fisk Jubilee Singers and headed the department of music. Beyond that, as a folklorist and field researcher, he and famed folklorist Alan Lomax also made the first recordings of blues legend Muddy Waters.

His contributions to Music City went even further, however. In an interview years ago, John Work III's sons told me that in the days when even the giants of 20th century music were subject to the indignities of segregated lodging, musicians occasionally opted to stay at the Works' house instead of "colored-only" hotels. Often the first hint the children would get of a famous guest would be their father late at night playing some new bit of folk music he'd recorded for whoever was in the house. In the morning, they'd come downstairs and find the likes of Duke Ellington at the breakfast table.

John Work III wrote at length about Muddy Waters and his approach to music — "Muddy Water [sic] is in great demand as a performer among the plantation folk, both Negro and white. Sometimes he assembles other players with him into a band; but most of the time he plays solo. He explains that it is necessary to use two different repertoires to accommodate the demands of white and Negro dancers. [...] Muddy Water would like to join the church but to do so would mean abandoning his guitar — a sacrifice too dear to make now."

Greenwood Park, a haven at the edge of town

The Entrance to Greenwood Park

Greenwood Park, Nashville's first park for African-Americans, opened the same year as the streetcar boycotts in 1905. Considering that Preston Taylor, one of the founders of the Union Transportation Co. streetcar line, was also the founder of Greenwood Park, this is probably not a coincidence. Taylor had had enough of racist white Nashville and decided to find ways to avoid it as much as possible. Now black Nashvillians could take Taylor's streetcar line past Taylor's Greenwood Cemetery to enjoy Taylor's blacks-only park.

Taylor advertised Greenwood Park, located near what is today the corner of Spence Lane and Elm Hill Pike, as "Owned by Colored People, Operated by Colored People, for Colored People." The park, in its day, was something to see. It had a clubhouse, a great hall, a skating rink, a spring, amusement rides, a ball field, a swimming pool and a zoo, among other amenities.

Though white Nashville appeared to be enthusiastic about "separate but equal" when it meant excluding black people from Nashville's public parks and recreational spaces, the city went to great lengths to sabotage Greenwood Park's success. City fathers went so far as to try banning parks within two miles of a cemetery, when Taylor's was the only one that fit the bill. Remarkably, their efforts failed. Greenwood Park thrived for 40 years.

Moses McKissack, the architect who built a legacy

Knowing Nashville's propensity for razing historic buildings, it may be dangerous to draw attention to the work of Moses McKissack, one of Nashville's most prominent architects. McKissack opened an office here in Nashville in 1905 and promptly set about designing homes, libraries and office buildings, many of which are still standing. After a few years his brother Calvin joined him, and their firm McKissack & McKissack was the first black-owned architectural firm in the nation — even if it is said that whites allowed them to apply for state licenses only because they expected the brothers to fail.

Not only didn't the McKissacks fail, their success gave black architects in other states grounds to challenge discrimination. Moses McKissack designed the Carnegie Library on Fisk's campus (now the Academic Building), Pearl High School (now MLK Magnet School), and the Morris Memorial Building, among others. Now the oldest minority-owned firm in America, McKissack & McKissack is still operated out of New York and Washington as separate businesses by his twin granddaughters, Cheryl and Deryl.

McKissack & McKissack is famous for its work making African-American heritage sites into usable spaces, including the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis and the Martin Luther King Memorial in Washington, D.C. The Morris Memorial Building in downtown Nashville is one of the earliest examples of its transformative efforts. Before the National Baptist Convention ordered the building constructed as their publishing house, the lot had an unsavory past — as one of the sites Nashville slave traders conducted their business.

The convention, however, was very clear that it wanted to change the site from a place of tragedy to one of hope. McKissack & McKissack made that transformation happen.

Mark McCann: the few, the proud, the Montford Point Marines

During World War II, black men were finally allowed to enlist in the U.S. Marines. But because the service claimed white Southerners would never agree to serve alongside African-Americans, black Marines weren't allowed to train with white Marines and were shuffled into support roles. Even their basic training happened at a segregated camp, Montford Point in Jacksonville, N.C.

Mark McCann was one of these so-called Montford Pointers. He enlisted in the Marines in 1943 and was trained in communications. He saw combat and rose to the rank of corporal before being honorably discharged in 1946. He enrolled at TSU, completed his education, and became a professor there. Eventually, he worked in various administrative roles. In all that time, he got married, had a family, grew old and retired.

In 2012, some seven decades after he enlisted, McCann and his comrades in the Montford Point Marines received the Congressional Gold Medal. The country had finally decided to stop pretending they didn't exist.

Much of Nashville's history remains hidden from itself, in part because America's history remains hidden from itself. As we slowly work to rectify that — and to acknowledge a past that many throughout the nation have purposefully ignored — we're richer for it.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com