There’s been plenty of debate lately about the future of The Fairgrounds Nashville — and about its present, too. But not enough people seem to talk about how the Fairgrounds Speedway has a horse buried in its infield, or how in 1910, it saw one of the first nighttime airplane flights in America. What’s more, the racetrack has been operational since 1891 — it’s a year older than the Ryman Auditorium. While its present form is up for discussion, The Fairgrounds Nashville’s long, strange history deserves some attention as well.

The land that became the present-day fairgrounds was taken from indigenous Tennesseans and given to John Rains — a Revolutionary War veteran and prolific swearer — by the U.S. government. Rains came to Nashville from what is now North Carolina with James Robertson and other war veterans. When Robertson built Fort Nashboro, Rains built his own fort on his 640 acres of land. When he died, his estate was split into lots that were given to his descendants.

There is little information about what the lot containing the fairgrounds held between Rains’ death in 1834 and the construction of the racetrack. But the Metro Nashville Archives was able to retrieve a document recording the sale of Lot 11 to the Cumberland Fair and Racing Association on April 11, 1891 — the lot was originally willed to the heirs of John Rains’ daughter, Barbara Rains Condon. The document references a dirt track and grandstands under construction, preparations for upcoming horse racing.

Aerial shot of the fairgrounds in 1958, from the Nashville Banner Archives

In 1891, the Cumberland Fair and Racing Association built the oval track, then called Cumberland Park — a precursor to the current racetrack. It was a dirt track, and built for Tennessee’s wildly popular horse-racing events. According to the book Nashville in the 1890s, the stalls could accomodate 350 horses, and the grounds held many high-profile events. In 1920, a renowned 32-year-old champion horse named John R. Gentry was buried in the infield, where he still rests today, though the grave is unmarked. According to one account, the horse’s funeral had more than 100 attendees, and featured a eulogy by the state librarian and archivist, John Trotwood Moore (who, as it happens, was also a virulent and open racist).

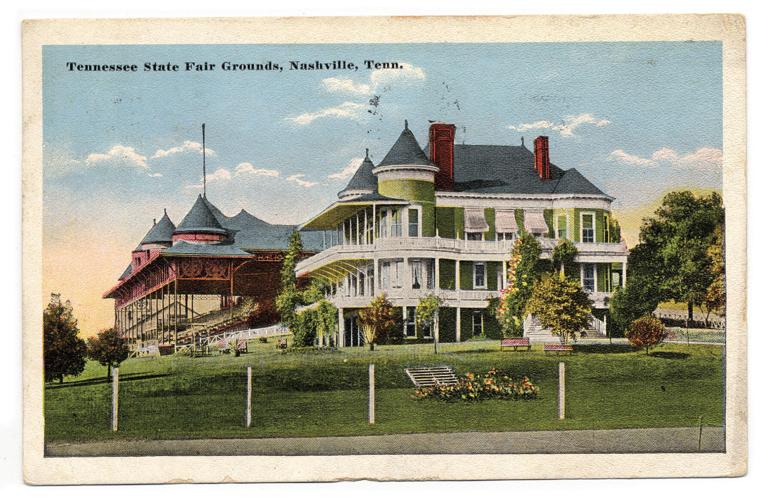

In 1906, Cumberland Park saw its first fair, a relocation of the already-popular Tennessee State Fair from what later became Centennial Park. Admission was 50 cents, and an early informational pamphlet notes the available nearby railroad stop on Wedgewood Avenue for people traveling from out of state. In 1910, the fairgrounds saw an aeronautics display from Charles K. Hamilton, who flew in the evening with a searchlight strapped to the bottom of his plane to the amusement of 20,000 attendees.

Horse racing continued at the park until the late 1950s, and the Tennessee State Fair continued at the fairgrounds until 2019. But now, most people know the fairgrounds for its auto racing. In 1904, the track saw its first auto races, which featured cars driving about 60 mph. Auto races remained popular and coincided with horse racing events until 1958, when the State Fair Lease Board paved over the dirt track. Once paved, the Fairgrounds Speedway hosted NASCAR Cup races, which saw wins from Richard Petty, Darrell Waltrip and Dale Earnhardt, among many others. The Cup left in 1985, but the track continued to host various racing events, including what’s now known as the Xfinity Series and the Camping World Truck Series races until the late 1990s.

Tennessee State Fair in 1970, from the Nashville Banner Archives

NASCAR races paved the way for other events. The Scene’s own J.R. Lind has written about the remarkable history of wrestling at the fairgrounds, which began in 1965 — just after a fire destroyed multiple buildings on the site. Fairgrounds wrestling would continue for 50 years, alongside the yearly Tennessee State Fair and ongoing speedway events.

But after the wrestling came discontent. In the ’80s, there was a federal investigation into flea-market extortion and kickbacks, and a 1999 Scene article paints a picture of the fairgrounds that’s all too familiar: “Revenue is down, turnover is high, the fun, lucrative days of auto racing are coming to a close, vendors and farmers are up in arms, the buildings are falling apart.”

In 2010, Mayor Karl Dean proposed tearing down the Fairgrounds Speedway and other buildings to create a mixed-use development, but pushback from racing fans led to a 2011 Metro Charter amendment requiring the flea market, auto races and other events to continue at the site, despite few infrastructure investments on the track.

This year, the fairgrounds will host Nashville SC at the soccer team’s new Geodis Park. And in March of last year, Mayor John Cooper signed a letter of intent with Bristol Motor Speedway to bring NASCAR back, though the plan was met with noise and financing concerns.

So who are The Fairgrounds Nashville for? At the turn of the 20th century, it was a place to see thoroughbreds with Nashville’s well-heeled. A few years later, you could take a train from out of state to see popular exhibitions there and eat lunch on the sprawling grounds. For many, it was a way to experience auto racing.

Even now, $15 will get you a ticket to see stock cars compete in the track’s 118th season. Yes, the infrastructure is indeed aging, and somewhere under the infield, there’s a champion horse in an unmarked grave. But the fairgrounds are a longstanding piece of Nashville’s character — a place that’s worn nearly as many hats as the city itself.