Willie Nelson’s Adidas tennis shoes

To understand the music belonging to the genre we now loosely call “outlaw country,” look not to tales of drugs and debauchery, nor to cadres of men with big beards, big hats and even bigger police records. Don’t even look to one album, or one particular sound. Look first to a pair of sneakers: some blue Adidas tennis shoes, only slightly yellowed in the soles and caps, that once were owned by Willie Nelson.

Sneakers might not exactly fit the mold for what we’ve come to expect of an era that included Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Bobby Bare Sr., Kris Kristofferson, Jessi Colter, David Allan Coe, Billy Joe Shaver, Guy Clark and any number of brilliant artists who defined the spirit of progressive country music in the 1970s. It certainly doesn’t fit the branding: Since that time, “outlaw” has blossomed into a full-scale segment of the marketplace, with entire advertising campaigns built on how to create the “outlaw experience” and, of course, sell products.

Nelson’s kicks are among the many pieces of memorabilia on display at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ’70s exhibit, which opens Friday for a three-year run. And they are as emblematic as anything else from a period when what was important was not to rebel for rebellion’s sake: The important thing was indulging vigorously in one’s creative spirit and taking ownership of art, as illuminated in the exhibit through never-before-seen artifacts, live footage, interview clips and interactive storytelling installations created in conjunction with Austin-based filmmaker and co-curator Eric Geadelmann, alongside the museum’s Peter Cooper and Michael Gray. For Nelson in particular, it was also about being comfortable — in his recordings, his environment, and yes, his footwear.

From Bare’s mink-skull-adorned hat (a gift from pal Nelson) to Marshall Chapman’s Stratocaster and the copper still that Tom T. Hall and the Rev. Will D. Campbell (“Bootleg Preacher” and the spiritual adviser to the crew) used to make whiskey, Outlaws & Armadillos is the story of one of country music’s most mythologized eras and cast of characters, told through the cities that shaped it all: Nashville, Tenn., and Austin, Texas. The story of the latter is centered on the Armadillo World Headquarters, a club that opened in the summer of 1970 and became the Lone Star State’s outlaw heartbeat. And though the romantic image of the period suggests forces in ferocious opposition — with Music Row in a battle against the artsy, free-loving world of Austin, or the suits vs. the outlaws — as Outlaws & Armadillos shows, the country music of the ’70s was more about synchronicity than anyone gives it credit for. If there was any war being waged, it was simply for artistic freedom.

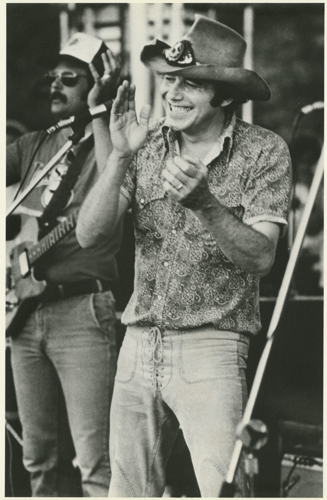

Bobby Bare Sr.

“Record companies didn’t want anything new, they wanted something like what was selling,” Bare tells the Scene. “But this gang of guys just wanted to do what they liked.”

It was Bare who called RCA head Chet Atkins and told him to sign Jennings, from a pay phone on the side of the road. Bare too went on to help define the follow-your-gut ethos of the decade through projects with the likes of Shel Silverstein, who was, for all intents and purposes, also very much an outlaw.

The moment that solidified Nelson and Jennings’ status as cultural “outlaws” once and for all was the release of 1976’s Wanted! The Outlaws, a compilation also featuring Colter and Tompall Glaser that was the first country album to be certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America. Though there’s some debate over when the term “outlaw” was officially coined, history generally credits it to Hazel Smith, working from the front desk of Hillbilly Central, Glaser’s studio and de facto outlaw home base, filled with booze and pinball machines. But that album is a mere fraction of the story at Outlaws & Armadillos, which shows that it’s mostly what came before Wanted that really defined the period.

“For some reason that record sold shitloads,” Bare says of Wanted. “They got labeled outlaws, but they never did take it very seriously. It was a PR game. They weren’t outlaws — they were just creative people who loved music and hanging out.”

The hall of fame’s Cooper agrees. “This was about creative people taking ownership of their own creativity,” he tells the Scene. “Musicians writing and recording the things that they wanted to write and record, and then recording them for posterity, in the ways that they wanted. Being an outlaw was not about skirting the law. It was about working outside of accepted and mandated norms.”

At the time, those norms meant artists often didn’t have a say in which producer they’d get to work with or which song they could sing. Labels mandated certain producers or engineers, or even players. That didn’t sit well with Nelson. After his home in Tennessee caught fire in 1969, he rescued his guitar and a pound of weed, and he moved back to his home state. Long gone were the slick suits of Nashville: In came the sneakers, the bandana and a good ol’ slice of redneck psychedelia.

“Willie Nelson put those sneakers on because they were comfortable,” says Cooper. “To say, ‘I’m not here to play dress up, I’m here to sing songs.’ ” While enjoying that freedom, Nelson wrote one of the seminal albums of the outlaw period, 1975’s Red Headed Stranger. Like Wanted, the record sold millions of copies, even though his label, Columbia, thought it sounded like a bunch of demos. The “outlaws” weren’t just rebelling for the hell of it: They were following their creative gut, and the sales proved they were right.

“Nowadays [the term outlaw] seems to have devolved into a frivolous label assigned to anyone who looks or sounds left of center,” country singer Joshua Hedley tells the Scene. Though Hedley’s music is much more inspired by the sounds coming out of Nashville in the 1960s, he’s often associated with the “outlaw” label because he has copious tattoos and writes songs that are pretty diametrically opposed to those of, say, Luke Bryan. “Long hair and beards weren’t what made Willie and Waylon outlaws. The type of music they made didn’t make them outlaws either. It was the fight. It was the rebellion against record labels and country radio. Country music in the ’60s and early ’70s was totally controlled by the industry. They told you what songs to record, who was playing on the session, and who was producing your record. And if you didn’t like that, then tough shit. Waylon and Willie fought for the right to make those decisions for themselves. That’s what made them outlaws.”

Indeed, the corporate constraints of Nashville weren’t a fit for Jennings.

“RCA was building refrigerators and TVs, and country music was something to keep it in the black,” Colter tells the Scene about Jennings, her late husband. He famously wrestled with RCA to record material on his own terms in the studio of his choosing — and won. “With Waylon, they were treating a thoroughbred like a donkey.”

Though the heyday of the outlaws is often held up as an example of the genre’s purity — and a foil to current pop-country — it might not have existed in full without the specific melding of two distinct sounds and cultures: rock and country. And the Armadillo World Headquarters, alongside its Nashville counterpart Exit/In, was at the center. Eddie Wilson, co-founder of the ’Dillo, named the place for the scrappy, hard-shelled animal that had become a mascot for Austin’s hippie subculture. “Both had endured ill treatment, disrespect and violent harassment, and yet both had survived,” Wilson writes in his memoir, also called Armadillo World Headquarters.

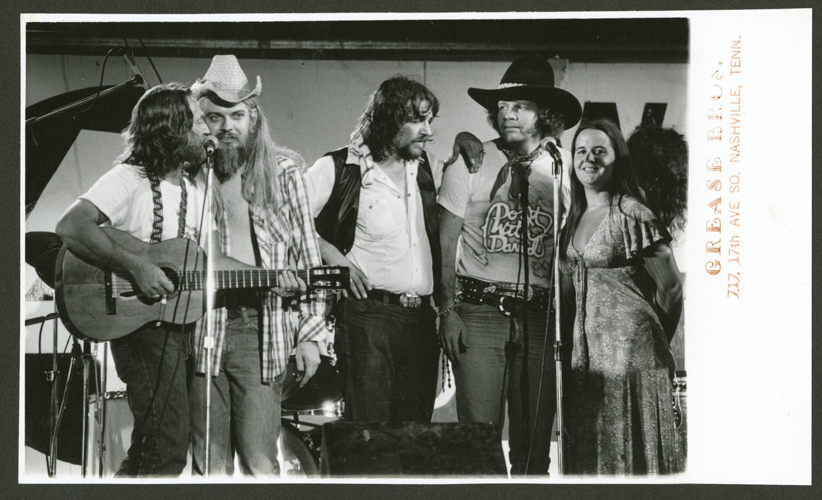

Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic, 1974. From left: Nelson, Leon Russell, Waylon Jennings, David Allan Coe and Tracy Nelson

Wilson and Jennings were both nervous before the night Jennings was to play the Armadillo for the first time. He had been recommended by Nelson for the gig. “Waylon was like, ‘What has Willie gotten me into, is this a rock club?’ ” remembers Colter.

Wilson was also unsure about the hardened country contingent flowing in: “Did I really want such people mixing with our hippies?” he writes. Somehow, it worked perfectly — rock and country, hippies and rednecks, all under one raucous roof.

“It was so much more than just country music,” Wilson tells the Scene. “It was the favorite venue of Frank Zappa, after all.”

Another important element in the surge of outlaw country’s popularity was the convergence of redneck culture with the loose hippie spirit. Wilson remembers talking to a doctor who was on hand at the very first of Willie Nelson’s famous Fourth of July picnics in 1973 — which is still the only time the doctor had patched up a bullet wound.

“The doctor said, ‘This hippie had a little piece in his back pocket, and he sat down on a rock and blew a bit of his ass off,’ “ says Wilson. A peace-loving hippie toting a pistol? It’s an image that speaks to the emerging culture-mash of what was happening down in Austin.

“It wasn’t so much a clash of culture as you expected it to be,” says Wilson. “And not just that it didn’t clash. We managed to get along. If there is a key word that’s overlooked, it’s ‘tolerance.’ ” Tolerance, and doing things their own way: If that’s what makes an outlaw, then they’ll take it.

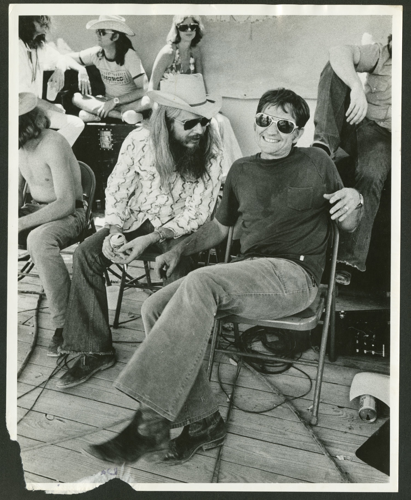

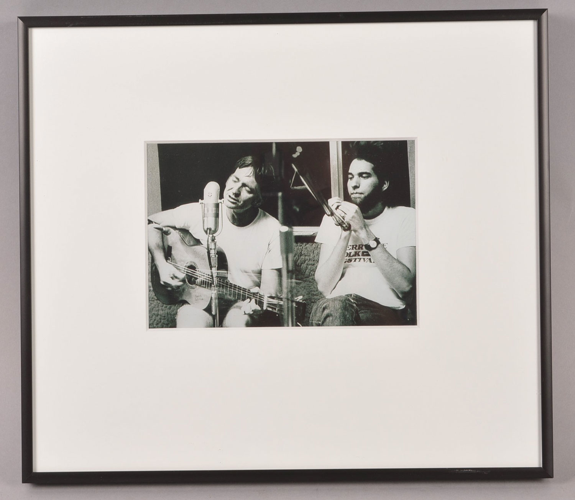

Willie Nelson and Mickey Raphael at Austin’s KOKE-FM, c. 1972

“Rock is inspired by country and vice versa,” Jennings told Chet Flippo in Rolling Stone back in 1973. He wasn’t protecting or saving anything other than artistic integrity. “Country fans are as smart as anybody, and it’s an insult to ’em when a program director says, ‘Well, that song’s too deep for our audience.’ Bullshit.”

Nelson had a similar conversation with Flippo in 1978. “I wasn’t considered commercial in Nashville, because my songs had too many chords in ’em to be country,” Nelson said. “And they said my ideas, the songs, were too deep. I don’t know what they meant by that. You have to listen to the lyric, I think, to appreciate the song.”

In 2018, the refrain is the same: Myopic country radio programmers are the ones losing their grip on what people want to hear, not the artists. From Margo Price to Chris Stapleton, Sturgill Simpson to Miranda Lambert and Jennings’ son Shooter, country and Americana are more fertile than ever. While country radio program directors still deem most of these artists’ creative output too “deep” for their audience, those listeners are buying up Stapleton albums by the million.

“I think Chris Stapleton hung the moon,” Bare says. “And I think Sturgill Simpson hung the moon, and Jamey Johnson did too.” Colter can’t say enough good things about Margo Price, or Shooter, her son with Jennings.

Flippo, who wrote the liner notes for Wanted, emphasized the enduring truth of the outlaw’s songs — and the unimportance of genre classifications.

“It’s not country and it’s not country rock,” he wrote, “but there’s no real reason to worry about labeling it. It’s just damned good music that’s true and honest.” No one was concerned with categories, no one was concerned about preserving some sort of time-honored heritage, and no one was concerned about keeping up any kind of outlaw image. They just wanted to make good music.

It was this “time of unprecedented truth,” as Cooper puts it, that helped Wanted, or Red Headed Stranger, Jennings’ Dreaming My Dreams or Colter’s single “I’m Not Lisa” sell so many copies — and it’s the road to this truth that Outlaws & Armadillos traces.

“My own prejudices against what I considered a kind of ‘y’all come an’ git it’ music have been overcome by the taste and sincerity of these two men,” Loraine Alterman Boyle wrote in the The New York Times (somewhat nauseatingly) in 1974 about Nelson and Jennings. “In brief, both are making country music that can even move those of us who think we despise it.”

And Nelson stuck to his convictions, even if it meant disappointing those around him. Harmonica player Mickey Raphael — whose harmonica case, fashioned by his German-immigrant father, sits in the exhibit — was gigging for Nelson back in the early ’70s. He remembers his boss turning down the experience of a lifetime in favor of what felt most pure.

“We got offered a world tour opening up for The Rolling Stones,” Raphael tells the Scene, “and I was so excited, but Willie turned it down. He said, ‘Why do I want to be an opening act when I can be here, in Austin?’ I didn’t understand that, but to give him credit, he was right.”

And what was brewing in the Lone Star State was, to Nelson, as thrilling as a Stones world tour. As Outlaws & Armadillos makes clear, Texas music was built on sonic diversity: You could find “accordion-fueled conjunto music that made its way up from Mexico; the polkas and waltzes — also to accordions — brought to the state by German and Eastern European immigrants; the country blues that arrived with freed slaves, and the zydeco and Cajun music that crossed the Louisiana border into southeast Texas.” That wellspring of influence nourished voices like Doug Sahm and Freda and the Firedogs, a wildly influential but criminally under-heard band that dominated the Austin scene. Or Jerry Jeff Walker, who released his seminal album ¡Viva Terlingua! in 1973. Or Kent Finlay, owner of legendary honky-tonk Cheatham Street Warehouse. There are many others like Finlay included in the exhibit: figures who are often left out of the mainstream narrative, but are as integral to the outlaw puzzle as anyone else.

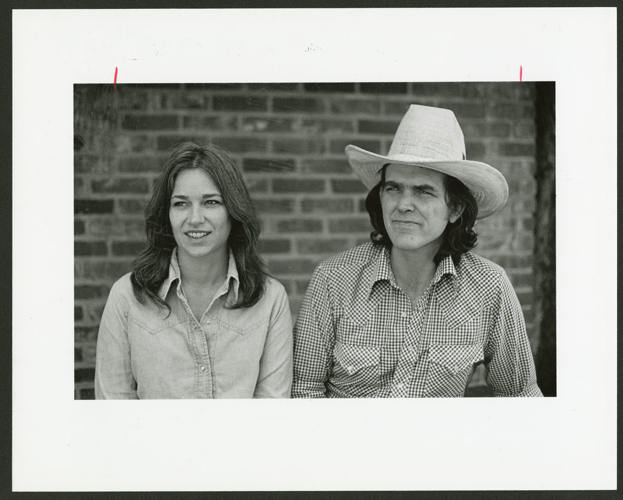

Susanna and Guy Clark

Back in Nashville, Townes Van Zandt, David Allan Coe, Susanna and Guy Clark and their friends — many of whom were just as inspired by Bob Dylan’s work in Tennessee as they may have been by classic country — were making the city equally as creatively fruitful. Often, they’d meet at places like the home of Sue Brewer, known as the Boar’s Nest, where it wouldn’t be uncommon to see Kristofferson or Jennings writing songs on the floor.

“There exists a notion that Nashville was some gray and corporate place,” says Cooper. “That notion is entirely erroneous. This was a music town full of creative freaks.” It was — and is. And contrary to the stark “outlaw” branding, the music that the likes of Van Zandt and Clark were making was as emotionally raw as anything else in existence, because real outlaws aren’t afraid to shed a tear.

“It was some of the most open-hearted, emotional music that I’ve ever heard,” says Cooper. On display in the exhibit is a painting Susanna Clark crafted of her husband’s denim shirt: the one on the cover of his debut LP Old No. 1. In person, it’s breathtaking. Also featured is the knife that Clark describes in his revered ode to his father, “The Randall Knife.”

“I’m no outlaw or outcast,” Guy Clark told the British magazine Omaha Rainbow in a section of an interview reprinted in Tamara Saviano’s Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark. “I don’t appeal to pop or country in particular, but I don’t feel alienated by either, and I’m influenced by both.”

“It has to be some of the best marketing in the history of the genre of country music,” says Nashville’s Tyler Mahan Coe, creator of the Cocaine & Rhinestones podcast, on the idea of the “outlaw.” “I think there are a lot of people who have this perception that it was the artists giving everyone the finger and telling them how it was going to be, as if the labels couldn’t have just said, ‘No.’ If the labels didn’t want to play along with this, it wouldn’t have happened at all.”

Like the rest of the Music Row machine, Atkins was often spun as the cowpoke trying to break Jennings’ bucking bronco, but Outlaws & Armadillos paints a different picture. After Atkins died, Cooper, at the time a staff writer at The Tennessean, called Jennings for comment for an obituary.

“Waylon went on about him,” says Cooper. “After the interview he said, ‘Thank you for your time. I love that man. Write him up as good as you can, hoss.’ ”

“Waylon wasn’t an outlaw,” says Bare. “He was one of the nicest humans I’ve ever met.”

Also among the exhibit’s “outlaws”? A pastor and a football coach. Outlaws & Armadillos takes great pains to illustrate characters like Will D. Campbell and University of Texas Longhorns coach Darrell Royal. Coach Royal was responsible for introducing Raphael and Nelson at a picking party after a University of Texas football game. Royal’s jacket hangs in the exhibit, as does the reverend’s whiskey still. “He was so emblematic of the spirit of the era,” says Cooper of Rev. Campbell. “He was the only person alive who could talk religion to Waylon Jennings.”

For many, Jennings and the rest of the outlaws were religion. But by the late ’70s, the mythology was getting to them. “Don’t you think this outlaw bit’s done got out of hand?” Jennings asked in a 1978 single of the same name. It had, and it never quite stopped. But what Outlaws & Armadillos shows is a group of artists who deserve to exist without being fenced in by the definition of “the outlaw” despite its convenience as an umbrella term. They didn’t want rebellion, or purity. They wanted the truth. They wanted music to evolve. They wanted to be free of labels or constraints. They still do.

“My personal taste leans to the old guys, but I love the Brothers Osborne, Chris Stapleton, Miranda Lambert,” says Raphael. Some of those new voices, like Jason Isbell, Amanda Shires and Ashley Monroe, will join the likes of Colter, Bare and Tanya Tucker for a sold out-concert at the museum’s CMA Theater on Friday. “I would never say anything bad about today’s music. There’s just gotta be room for growth, and for change.”