Loretta Lynn

Loretta Lynn

A head on the Mount Rushmore of country music

Lay out a collection of Loretta Lynn’s records — grab 1960s classics like Don’t Come Home a Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind), at least one of her iconic LPs of duets with Conway Twitty, even Van Lear Rose, the Grammy-winning album she made in 2004 with Jack White — close your eyes and point. You’re almost certain to land on a track that has helped generations of musicians and fans define “a country song.” And often as not, it was a song she wrote herself. Born in Eastern Kentucky near the mining town of Van Lear, Lynn grew up in poverty, a coal miner’s daughter as in her hit song and autobiography of that name. She died Oct. 4 at her ranch in Hurricane Mills, Tenn., at age 90, a towering figure in country history.

Lynn didn’t think of herself as a feminist, and examining her work without considering stereotypes and their roles in country music ignores important perspectives about how the industry needs to change. But the way she took command of her career and image — speaking the truth as she saw it during times when many mainstream entertainers shied away from singing about sexual freedom and equality — was fundamentally inspirational and didn’t diminish her fan base. She remains one of the best selling and most influential artists in the history of the genre. Despite suffering a stroke in 2017, after which she seldom appeared in public, Lynn continued recording. Right through her most recent album, 2021’s John Carter Cash-produced Still Woman Enough, she was singing powerfully and writing with her characteristic sly wit, hard-won wisdom and remarkable economy of language. —Stephen Trageser

Beegie Adair

Beegie Adair

Pianist extraordinaire, leading light of Nashville jazz

Beegie Adair was a keyboard wizard who could take the melody of any familiar standard and turn it inside-out on the piano in so many ways that it sounded like a new song. Meanwhile, she was such a gifted and versatile stylist that her extraordinary 60-year-plus career included appearances on more than 100 LPs (including her own extensive catalog) and performances with a host of greats across the musical spectrum, from Cannonball Adderley and Duke Ellington to Johnny Cash, Vince Gill and Dolly Parton.

Adair, who passed on Jan. 23 at age 84, was a prolific artist who at various points was a member of the house bands for The Johnny Cash Show and The Ralph Emery Show, among others. She also had a monumental impact on the Music City jazz scene as an instructor and mentor. Among myriad other accomplishments — not to be forgotten: the jingle business she ran with her late husband, fellow music educator and superb musician Billy Adair — she was a pivotal figure in the development of the Nashville Jazz Workshop. Beegie Adair was also a vital bandleader. Her trio with bassist Roger Spencer and drummer Chris Brown was Music City’s first jazz group to appear at the storied Carnegie Hall, and she headlined at Birdland with vocalist Monica Ramey.

Adair was deeply respected throughout the industry. It’s hard to think of something in the business that she didn’t do, or a person she didn’t know. I remember once being on a panel with her discussing the film Jazz on a Summer’s Day, when she casually commented on how many people in the film she either knew personally or had played with — or in many instances, both. More importantly, though, it’s impossible to recall her bragging about her greatness, or to think of someone she didn’t make time for. —Ron Wynn

Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper

Historian, songsmith, guiding light in country music journalism

Peter Cooper — a native of Spartanburg, S.C., who was an outstanding musician and educator, a top-notch country music journalist and most recently a senior staffer at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum — made his way to Nashville in 2000. He took on the job of writing about country music for The Tennessean with enthusiasm, a depth of knowledge of and reverence for the craft, and an elegant command of language that would make any scribe jealous. (Among those who became a regular reader: Johnny Cash.) He didn’t limit his scope to considering music from afar: A standout singer-songwriter, Cooper honed his chops with encouragement from friend and songsmith Todd Snider and collaborated closely with pedal-steel legend Lloyd Green. Cooper found a longtime musical partner in Eric Brace. Among other projects, the pair released three records as a duo (plus two more as a trio with Thomm Jutz), ran an indie label called Red Beet Records and took the lead on a project to re-record revered songwriter Tom T. Hall’s classic record for children, Songs of Fox Hollow.

Following music-journo adventures that included sparring with Toby Keith and writing the epitaph on George Jones’ tombstone, Cooper left his post at The Tennessean in 2014. He joined the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum as a writer and editor, a role that later expanded to include directing and producing content like the Voices in the Hall podcast and the Live at the Hall video interview and performance series. Friends, family and colleagues were shocked to hear that Cooper, age 52, was in the hospital with life-threatening injuries following a fall. Family confirmed that he died in his sleep on Dec. 6. Cooper’s former Tennessean colleague Dave Paulson included in his obituary a line from Cooper’s 2017 book Johnny’s Cash and Charley’s Pride that continues to resonate in the wake of his passing: “Now, for sure, you need a good bullshit detector, and you shouldn’t rant, and you shouldn’t cheerlead. But objectivity is dispassionate. And we’re in the passion business. We’re trying to make people feel something different than what they felt before they read our words.” —Stephen Trageser

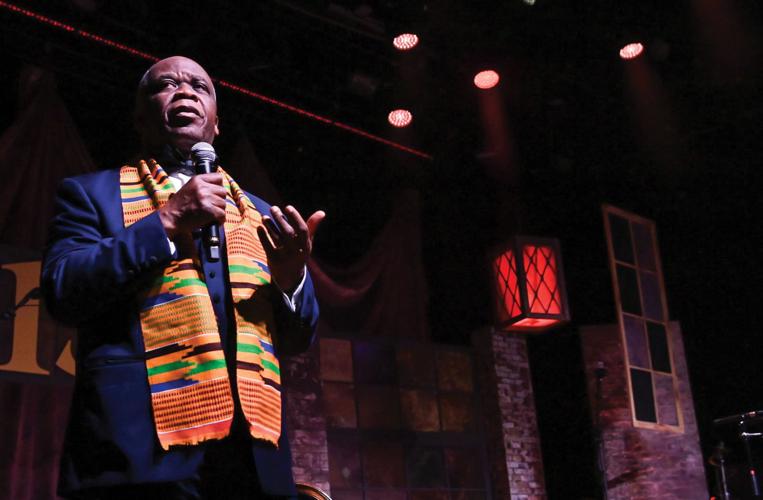

Dr. Paul T. Kwami

Dr. Paul T. Kwami

Director of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, shepherd of legacy

Dr. Paul Kwami accomplished one of the toughest tasks imaginable in music: He helped update and popularize a historic entity without significantly altering or destroying what made it great. As the music director for the famed Fisk Jubilee Singers from 1994 until his death Sept. 10 at age 70, Kwami brilliantly handled the task of making them relevant and important to 21st-century audiences while retaining the qualities that made them such legendary figures since their debut in 1871.

Beyond being a demanding but fair taskmaster, he made certain the 16 vocalists (equally divided between men and women) understood the cultural and historical significance of the ensemble’s material. As part of that mission, he took the singers to Ghana in 2007 for a celebration of the 50th anniversary of that nation’s independence and the fact that the prominent racial and social justice advocate Dr. W.E.B. Dubois (also a Fisk graduate) was buried there.

During Kwami’s tenure, the group was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame, received the National Medal of Arts and was recognized with the Americana Music Association’s Legacy of Americana award. Kwami also involved the singers with artists from outside the gospel sphere as he stepped up the group’s recording activities. Among many other projects, they appeared in Jonathan Demme’s 2006 Neil Young concert documentary Heart of Gold, and they cut the magnificent Shannon Sanders-produced LP Celebrating Fisk! The 150th Anniversary Album featuring collaborations with Keb’ Mo’, Ruby Amanfu (who is Dr. Kwami’s niece) and many more. The group had been nominated for Grammys multiple times, and a compilation album they contributed to had won in its category — but in 2021, Celebrating Fisk earned the Fisk Jubilee Singers their first Grammy for their work on their own. —Ron Wynn

Joe Chambers

Founder and CEO, Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum

Joe Chambers knew musicians as well as anyone in Music City — he was at various points a guitar-slinging rocker, a chart-topping songwriter for artists including Ricky Van Shelton, Randy Travis, Tammy Wynette and Emmylou Harris, a record producer, and the owner of instrument stores.

It’s significant, then, that his deepest admiration was for the session musicians who don’t draw the huge spotlight of superstar onstage talents, but rather turn melodic ideas and notes on a page into the songs adored by millions. Chambers founded Nashville’s Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum in 2006 as a place to honor session musicians, engineers and producers. The museum, now located at the Nashville Municipal Auditorium, holds everything from one of Motown legend James Jamerson’s bass guitars to instruments owned by The Wrecking Crew players, and recording hardware used at Alabama’s famous Muscle Shoals Sound Studio.

Chambers’ idea was a hit, especially among industry veterans. After his visit, Neil Young was quoted as saying: “You can see the hood ornament on the car if you go to The Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame. But, if you want to look at the engine and see what’s making it go, then you go to the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum.” —Cole Villena

Hargus “Pig” Robbins

Friend and brother, exceptional pianist, country music legend

Hargus “Pig” Robbins’ place in Nashville music history is undeniable. The masterful pianist, who died Jan. 30 at age 84, was the Country Music Association’s Instrumentalist of the Year in 1976 and 2000. He was also inducted into the Musicians Hall of Fame (along with the Nashville A-Team of session players) and the Country Music Hall of Fame. His 1977 album — titled Country Instrumentalist of the Year — won a Grammy for Best Country Instrumental Performance. But his peers considered him a friend and a brother, who happened to be one of the greatest musicians the city has ever known.

Born in Spring City, Tenn., and blinded in an accident at age 3, Robbins entered the Tennessee School for the Blind in Nashville at age 7, where he studied classical piano. He began playing sessions in 1957, and his career as a studio player really took off in 1959 after he contributed the lively honky-tonk piano parts to George Jones’ hit “White Lightning.” In a career spanning more than six decades, Robbins played on countless country hits including “Crazy” by Patsy Cline, “Behind Closed Doors” by Charlie Rich and “Coal Miner’s Daughter” by Loretta Lynn. Robbins also appeared on a wide variety of pop, rock, R&B and jazz recordings, and may be best known for his outstanding performances on Bob Dylan’s 1966 album Blonde on Blonde. His work on that historic record led to sessions with folk and rock artists running the gamut from Joan Baez and Loudon Wainwright III to Mark Knopfler and Ween. —Daryl Sanders

Naomi Judd

Country music icon

This year should have marked the beginning of a deserved and long-overdue career renaissance for Naomi Judd, who made country music history as one-half of the award-winning and immensely influential duo The Judds. Alongside her daughter Wynonna, the Kentucky native became one of the genre’s biggest stars seemingly overnight. In 1984, the sentimental single “Mama He’s Crazy” became the first of eight consecutive No. 1 hits for The Judds, leading to sold-out shows, multiple Grammy wins and other industry accolades.

That success was born from Naomi’s boundless determination to be heard and seen. A nurse and single mother of two daughters, Judd showed her music to anyone in Nashville who would listen, unmoved by the sexism and rejection she faced along the way.

In an industry where discussing mental health is still mostly taboo, Naomi was open about the challenges she faced throughout her life. Each day, she battled with the lingering effects of childhood trauma, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression. But she drew joy from her music and the support of her family and fans. Judd’s sweet yet powerful voice, fiery red hair and flamboyant fashion sense captured the attention of any room.

Just one day before she was to be inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, Naomi Judd died by suicide on April 30. She was 76 years old. Fans, family and friends have honored her legacy throughout the year; an expansive tour, arranged well in advance of Naomi’s death, was carried out with Wynonna sharing the stage with tons of guests. —Lorie Liebig

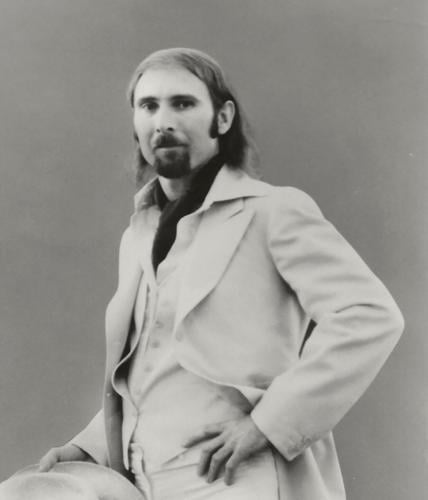

Jim Seals

Jim Seals

Humble hitmaker

Texas native Jim Seals, lead vocalist in the hit ’70s soft rock duo Seals & Crofts, passed away on June 6 at age 79. He succumbed to an ongoing illness at his home in Hendersonville surrounded by his family and closest friends.

In the 1970s, Seals and his musical partner Dash Crofts scored multiple platinum and gold albums and were a constant presence on pop radio airwaves. The duo had eight singles that went to No. 21 or better on the Billboard Hot 100, most notably “Diamond Girl” and “Summer Breeze.” But the musical winds were blowing in a different commercial direction by the end of the ’70s, so the duo decided to call it quits in 1980. They did from time to time, however, reunite to perform for special gatherings of the Baháʼí Faith, of which they both were devout members.

Seals and his family moved to Costa Rica in 1980 and lived there until they relocated to the Nashville area in 2005, settling in Hendersonville, which was home to his brother Dan Seals, a successful recording artist. Between 2005 and 2008, the brothers performed together as Seals & Seals, doing more than 100 dates with a band that included Jim Seals’ sons Joshua and Sutherland. They also recorded a number of tracks during that time, which have never been released. After his brother died in 2009, Seals continued to write and record for his publishing company until he suffered a stroke in 2017.

“Jimmy was passionate about three things — faith, family and fun,” his wife Ruby says. “And for him, the fun was music.” —Daryl Sanders

Edward “Moe” Denham Moerschel

Session player, DJ, Hammond B3 lover

Known around Nashville and nationally for his contributions to the jazz scene, Edward “Moe” Denham Moerschel worked with the likes of Count Basie, Neil Young, B.B. King and more in his time as a session musician. He devoted his whole life to music, starting with piano at age 6 and taking up the Hammond B3 organ at age 11 — the instrument on which he would ultimately make a name for himself.

“My mom, when she bought the Hammond organ, I was only 11 years old, but I was fascinated by all the draw bars and the sounds, and it’s been that way ever since,” he told NPR in a 2006 interview. He also mentioned at the time that he had collected eight B3 organs, and had a vanity plate reading “B3 PLYR.”

The Seattle-born organist was a veteran of the U.S. Air Force, after which he became a state trooper in Maine. He eventually moved on to radio, becoming a disk jockey for multiple stations, eventually settling in as the news director at WGNS in Murfreesboro. Moe Denham, as he was known, is survived by his wife Susan and two daughters, Beth and Kate Moerschel. He died on Dec. 23, 2021, at age 77. —Connor Daryani

Jeff Carson

Jeff Carson

Country singer turned Franklin police officer

After cutting his teeth as a performer at Nashville’s Opryland Hotel, Jeff Carson made his introduction to the larger music world as a solo recording artist in 1995. Jeff Carson, his 11-track debut, spawned a No. 1 Billboard country hit (“Not on Your Love”) and an Academy of Country Music Award for Video of the Year for “The Car,” a sweetly sentimental celebration of family and fatherhood.

Carson had 14 charting singles throughout his career, including “Holdin’ Onto Something,” “Real Life (I Never Was the Same Again)” and covers of songs like “I Can Only Imagine.” In 2008, Carson traded in his guitar for a Franklin Police Department badge, becoming a fixture in that community over the next decade. He called his graduation from the police academy his “proudest moment,” saying, “Being in law enforcement was something that I’ve always wanted to do.” He won six commendations and a Chief’s Award for Excellence during his tenure.

But Carson’s music career wasn’t entirely over. In 2020, he rereleased “God Save the World,” a track he’d recorded nearly two decades earlier. Weeks after Carson’s death, country music performers including Michael Ray, Lee Greenwood and Rhett Akins gathered to perform a memorial concert honoring his life. —Cole Villena

Deborah McCrary

The singing nurse

Deborah Person McCrary, beloved member of The McCrary Sisters gospel vocal quartet, passed away June 1 at age 67. McCrary was the second-oldest daughter of the Rev. Samuel H. McCrary, a founding member of the legendary gospel group The Fairfield Four. Along with her sisters Ann, Regina and Alfreda, she performed and recorded with some of the biggest names in popular music, including Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, Isaac Hayes, Stevie Wonder, Gregg Allman, The Black Keys, Hank Williams Jr. and Carrie Underwood. She also appeared on the five albums the group has released under its own name.

McCrary was a professional nurse, so although she sang with her sisters at Nashville performances and on recordings after the group was formed in 2010, she didn’t start traveling full time with them until 2012. Her sisters called her “the singing nurse.”

“What everybody really needs to know about Deborah was her passion to sing music that would make people smile and change people’s heart from bitterness and darkness to light and love,” her sister Regina says. A contralto, McCrary had a wide vocal range and could sing any of the harmony parts. But following a stroke in 2013, she was limited to the lower part of her range, so she anchored the bottom end of the group’s dynamic sound.

“The awesome bottom, baby,” says Regina. “Ever since Deborah has been gone, we’ve missed that bottom.” —Daryl Sanders

Ben Kerby Farrell

Promoter, storyteller, legend

“Legend” is a term typically used for entertainers like Elvis Presley, Elton John, George Strait, Barbara Mandrell, Randy Travis and Neil Diamond. Concert promoter Ben Farrell worked with all of those acts and legions more and was as legendary in the music business as any of them.

Farrell attended Lipscomb University on a baseball scholarship, played minor league ball and spent two years in Vietnam before taking his first — and last — job, with Varnell Enterprises in Nashville in 1970. He assisted with marketing, promotion and on-site show supervision, then built the company’s roster of clients by signing future and established superstars, rising to be president.

Farrell was legendary for attention to detail, strategizing and a ’round-the-clock work ethic. He was legendary for his total recall of names, dates, venue seating capacities and the exact number of tickets sold at any given facility by any given artist on any given date. He was legendary for his loyalty, and the loyalty he inspired — he was Garth Brooks’ promoter for more than 30 years. He was legendary for his Forrest Gumpian knack of being everywhere. He was legendary for his love for his wife, daughter and UT football, his thirst for knowledge and his remarkable skills as a storyteller who could capture entire rooms.

Most of all, Ben Farrell was legendary for all the secrets he knew — and never, ever told.—Kay West

Shonka Dukureh in Elvis

Shonka Dukureh

Revered singer, teacher and actor

Raised in Nashville, Shonka Dukureh held a degree in theater from Fisk University and another in education from Trevecca Nazarene University, and was a much-loved teacher and mother of two. A lifelong singer in church, she was also regarded as one of the finest gospel vocalists in town. As WPLN’s Nina Cardona reported, it was no big surprise when Dukureh was called to record as part of a choir for Baz Luhrmann’s fantastically surreal biopic Elvis. However, it was a bit of a shock — and a thrill — to learn she’d been cast in the film as phenomenal R&B singer Big Mama Thornton, whose original recording of “Hound Dog” inspired Elvis Presley’s own hit version early in his career.

“I knew to really pay tribute to her, I had to tap into myself, my own self-confidence, my own voice,” Dukureh told Cardona. “Because she was very adamant that she only had her voice: No one could sing like her and she sang like no one. So I had to also embrace that approach to music. I didn’t try to sing it like her, but I knew I needed to definitely sing it in a way that she would give me a hand clap, in a sense.”

A remix of Dukureh’s rendition of “Hound Dog” featured rapper Doja Cat, who invited Dukureh to join her onstage at Coachella in the spring. She had also begun work on an album of blues music inspired by Billie Holiday. Then, on July 21, the devastating word went out that Dukureh had died at age 44, of what was later revealed to be natural causes. —Stephen Trageser

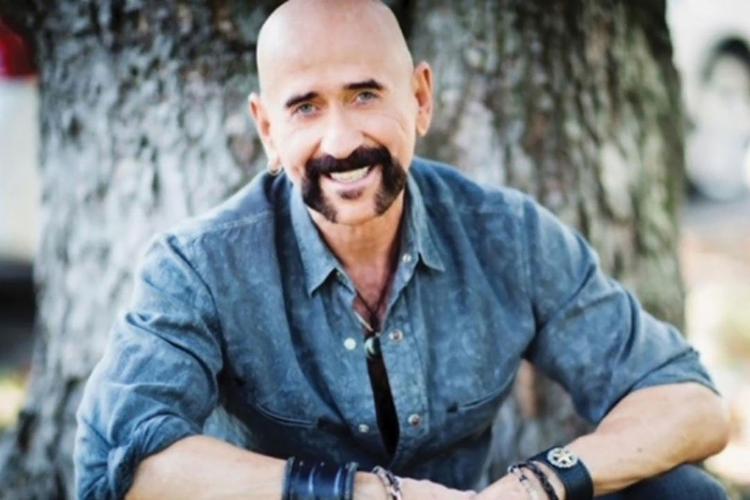

Jimbeau Hinson

Jimbeau Hinson

Songwriter, performer, mentor, advocate

The story goes that Loretta Lynn “discovered” Jimbeau Hinson when he was just 14 years old. But truth is the irrepressible Mississippi-born son of a mechanic and a truck-stop waitress discovered himself years before that.

By the time he talked his way backstage to meet Lynn, the self-taught pianist was a stage performer and had his own radio show. But he set his sights on Nashville at 16 and never looked back, joining The Wilburn Brothers road show and signing to their publishing company. He had his first ASCAP award at 18 and was a prolific writer throughout his career, with songs recorded by country artists like The Oak Ridge Boys, Patty Loveless, Reba McEntire and Kathy Mattea. His collaborations with Steve Earle on “Hillbilly Highway” broadened his reach, and Hinson succeeded in multiple genres of music. Despite his superb voice and showmanship, Hinson did not succeed as a recording artist, likely due to his openness about his bisexuality, a major-label deal-breaker then.

In 1985, Hinson discovered he had HIV/AIDS. Determined not to reveal the diagnosis, he retreated to the rural property he and his beloved wife Brenda Fielder had and spent the next decade battling the disease. Thanks to advances in treatment, he recovered from a near-death experience, regained his life and his career and dedicated himself to advocating fearlessly and fiercely for AIDS/HIV awareness. He was working on his memoir The All of Everything when he passed away. Hinson is remembered as a mentor to aspiring young songwriters, one of whom shared advice he gave her for writing, and for life. “You gotta leave a little glow wherever you go.”—Kay West

Scotty Wray

Guitarist, road warrior

In an industry full of sugar-coated glitz, Scotty Wray stood out like a sore thumb — an epiphany of rock ’n’ roll. He chain-smoked cigarettes, ate nothing that resembled a vegetable and could pick an acoustic guitar so that if you closed your eyes, you’d think it was Doc Watson in the room with you. His relationship with Miranda Lambert was beautiful: One moment, both of them would be putting a foot down to argue their point, and the next, they’d be holding each other up with love and care to get through the next day. A real deep bond they had. He had a laugh that could shake a wall down, and we can still hear it today. Keep it country, bud. We all miss you dearly. —Spencer Cullum

Charlie Monk

The Mayor of Music Row

In the multitude of photographs of Charlie Monk from his six decades in radio and the music business — in which he stands beside the biggest celebrities in the business or with his arm draped around the shoulders of a newcomer — he is not smiling. The man who became known as The Mayor of Music Row is clearly laughing. Maybe he just told one of his corny jokes or one of his countless stories. Maybe someone poked fun at him. Whatever it was, Charlie Monk’s joie de vivre was genuine, authentic and contagious, and he parlayed personality, professionalism and undaunted optimism to build a life the kid who grew up dirt poor dreamed of.

Monk’s entry to the entertainment business was humble, sweeping floors in his South Alabama hometown radio station until he nabbed the weekend DJ gig. After serving in the Army, Monk did the typical radio journey — small market to bigger market, on-air personality to program director. In Tennessee, he landed at Murfreesboro’s WMTS before moving in on Music Row. He left the broadcast booth to work for ASCAP, co-founded the Country Radio Seminar, produced and hosted the New Faces show for 40 years, and became a song publisher. In 2004 he returned to radio to help launch SiriusXM in Nashville, hosting two popular shows.

He was inducted into the Country Radio Hall of Fame and the Alabama Music Hall of Fame and received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Tennessee Radio Hall of Fame. Until recently, Monk could be found every weekday morning at the Green Hills YMCA; his workout consisted primarily of strolling around the massive cardio room, checking in with friends and strangers alike. If there were a Hall of Fame of Schmoozers, the Mayor of Music Row would be the first one in the door, laughing all the way. —Kay West

Ronald Lee Huntsman

Pioneer of Nashville FM radio and concert promotion

Ron Huntsman had much to do with the creation of our city’s FM radio scene, and if you went to any of the early Charlie Daniels Volunteer Jam shows, you were enjoying his handiwork.

Ron passed away on July 2 at 78. As program director for WKDA-FM (now WKDF, once the city’s dominant “album-oriented rock” station) starting in 1971, he preceded DJs warmly remembered by many local boomers, including Hunter Harvey, David Hall and Dave Walton. —E. Thomas Wood

Drew Alexander

Music publisher

In the final days of 2021, veteran Nashville music publisher Drew Alexander died at age 52 following complications from a short illness. Alexander was the son of former Tennessee Gov. and U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander and Leslee “Honey” Alexander, who died about one year later.

Drew Alexander spent much of his life steeped in music, growing up in Nashville and studying music at Ohio’s Kenyon College. After graduation, he began his music industry career as a receptionist at Curb Records; in 2017, he left the firm as vice president of publishing. He then founded Blair Branch Music, acting as a consultant for entities in government, entertainment and nonprofit work. In addition to his “day job,” Alexander served on a number of local boards, including Belmont School of Music, the Community Resource Center, Leadership Music and the Recording Academy. He was also known for hosting writers’ retreats at locales such as his family’s Blackberry Farm home, with participating artists including Kelsea Ballerini and Bill Anderson. Alexander had two children, Lauren Blair Alexander and Helen Victoria Alexander. —Brittney McKenna

Ann Tiley

Songsmith, painter, candid chronicler of Nashville in motion

While Nashville lay wrapped in a blanket of snow on Jan. 7, a piece of the city’s soul slipped away. Ann Tiley, a fixture of the most democratic music scenes in Music City for more than four decades, died. Her longtime partner Tim Jones shared the sad news that she had suffered a brain aneurysm.

Around 1979, Tiley’s love of Bill Monroe and Townes Van Zandt inspired her to move to Nashville from her home in West Virginia. Among the friends she made here was John Allingham, who co-founded the Music City folk institution The Cherry Blossoms and the equally venerable artists’ hangout and jam session Working Stiff Jamboree. As Tiley explained to late, great Scene editor Jim Ridley in 1997, Allingham encouraged her as she began writing her own songs. She developed a distinctive, intimate, diaristic approach, singing and accompanying herself on acoustic instruments like guitar or mandolin; friends and associates joined in on fiddle and harmonica, among others.

Tiley also painted extensively. Her friend Peggy Snow, also of The Cherry Blossoms, is a visual artist too, known for preserving buildings that are slated for demolition in her work. Tiley’s paintings, on the other hand, are a lot like her songs. They contain impressions of people she knew, places she performed — Springwater, Bobby’s Idle Hour, Brown’s Diner — and other scenes of life around the town she called home. In both, she created a unique historical record that traces the character of a city in motion. With the breakneck pace of change in Nashville, the immense value of work like Tiley’s is too seldom appreciated. —Stephen Trageser

James Ace “Jimi” Reilly, aka TN Jim

Skateboarder, rapper, graffiti artist

On May 14, Jimi Reilly passed away in New Jersey. In our youth, he was mostly here in Nashville with his sister Colleen and his mom Lindy, but would sometimes stay with his dad in Kearny, N.J. I believe I met him skateboarding in front of Hillsboro High School, though we weren’t old enough to attend school there yet. We became part of a crew of skaters, initially called Linus and later renamed Elmo. In addition to myself and Jimi, it was Matt Chenoweth, Baker Hoffman, Jay Huff — and Matt Arnn, who headed up the filming operation and edited several skate videos we made in the ’90s. Beyond the influence of the skate videos (both locally and elsewhere), Jimi had more direct connections to the world of hip-hop in New Jersey and New York City, and he started both painting graffiti and freestyling as a teenager. In that way, his influence on the rest of us in Nashville was enormous. The first time I ever attempted to freestyle was at the age of 16 with Jimi.

By the end of the ’90s, Jimi, his mom and his sister all moved to New Jersey, and to my knowledge, they didn’t have much contact with Nashville until Jimi returned in the mid-2000s. Since I had started producing beats and gotten more serious about writing rhymes, the two of us started recording songs. The result was a project called Charcoal Filtered, which was officially released with a party at The Juice Bar on Gallatin Avenue in 2008. We got a lot of love from the hip-hop community in Nashville and performed regularly at an event called Sound Therapy. Some of my best memories include skating around Nashville and hanging out with Jimi and the rest of our friends as teenagers, and making music and doing shows with him later on. It was always a party with TN Jim. Though I had not been in touch with him much since about 2010 or so, in recent years, he had been more serious about his visual artwork and moved around between Asheville, N.C.; Chattanooga; Nashville and New Jersey. He was a certified climber/rescuer for Emergent Wireless Solutions and Telco Mills Inc. He is survived by his mother Lindy Reilly, his sister Colleen Reilly and his niece Alana Ward, all of whom are currently in New Jersey. —Alex Davis-Smith, aka AL-D

Ray Edenton

Studio guitar maestro, country rhythm innovator

Guitarist Ray Edenton, an important part of the Nashville Sound for almost 40 years, passed away in Goodlettsville on Sept. 21 at age 95. Born in and raised in Virginia, Edenton moved to Nashville in 1952 and started playing on the Grand Ole Opry that year, specializing in acoustic rhythm guitar. He made his career breakthrough in the studio with The Everly Brothers, playing a second part in tandem with Don Everly’s aggressive guitar on their early hits.

At first Edenton was valued on sessions for his ability to provide rhythmic drive on country recordings, which at the time typically didn’t use drums. As instrumentation expanded, he brought country rhythm guitar into a new era by creating new “high-strung” tunings that complemented a conventionally tuned acoustic, creating a bigger and fuller sound. This doubling of guitars was often used to provide a lush bed of acoustic guitars, as can be heard on thousands of country records even up to the present day — a sound that can be directly tied to Edenton’s innovations and a defining part of the original Nashville Sound.

There is hardly an important Nashville recording artist of the era that Edenton did not work with during his long career. His consummate skill, creativity and many innovations led to him playing on more than 10,000 sessions before his retirement in 1991. In 2007 he was inducted into the Musicians Hall of Fame, and he was also honored as a Nashville Cat by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. —Pete Finney

Glenn Meadows

Stellar mastering engineer

Audio mastering is thought of as the “final creative step” in producing a recording, the processing of audio so that it sounds its best on the medium from which you’re listening to it. In recent decades, mastering for maximum loudness has been an industry standard (many would argue to the detriment of the sound quality), but for a long time before that, it was a subtle art.

One of the finest practitioners in this field over the past five decades was Glenn Meadows. A native of Long Island who gravitated toward audio technology as a teen, Meadows attended Georgia Tech and became involved in the studio scene in Atlanta before making his way to Nashville in 1975. He intended for a job at legendary mastering facility Masterfonics to be a stepping stone, but he stayed with the firm for more than 30 years, overseeing its extensive growth once he took over leadership in 1989. Meadows moved over to Mayfield Mastering in 2011. You’d need very long arms indeed to get them around his list of credits, which includes Jimmy Buffett, Tanya Tucker, Billy Joe Shaver, Shania Twain, Taylor Swift and dozens and dozens more.

A two-time Grammy winner who was also known for volunteer projects like running sound at the Nashville Rescue Mission’s Friday night coffeehouse, Meadows was recognized by the Audio Engineering Society with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019. Following a brief illness, he died July 7 at age 73. —Stephen Trageser

Anita Kerr

Anita Kerr

Singer, arranger, composer, an architect of the Nashville Sound

Memphis native Anita Kerr, the award-winning singer, composer and arranger who first made her mark on music history in Nashville, passed away Oct. 10 at age 94.

As leader, arranger and soprano for the Anita Kerr Singers, which included Gil Wright, Louis Nunley and Dottie Dillard, Kerr was one of the architects of the Nashville Sound. The group appeared on thousands of recordings in the city during the ’50s and early to mid-’60s, including major pop hits such as Bobby Helms’ “Jingle Bell Rock,” Roy Orbison’s “Only the Lonely” and Brenda Lee’s “I’m Sorry.”

“I heard all of the stories about her genius, and I saw it myself,” recalls legendary guitarist and producer Jerry Kennedy. “She was a fantastic mind in the studio.”

“She was arranging for the Anita Kerr Singers on the spot in the studio,” session ace Charlie McCoy says. “And the stuff they did, especially with Brenda Lee — it was so great.”

In addition to backing other artists, Kerr’s group made four albums of its own for RCA between 1962 and 1965, winning a Grammy for Best Performance by a Vocal Group for the 1965 LP We Dig Mancini. Wanting to work on more pop sessions, as well as jazz and orchestral recordings, Kerr relocated to Los Angeles in 1965, re-forming the Anita Kerr Singers with L.A.-based vocalists. There she made a series of albums for Warner Bros. and Dot. In 1970, she moved with her second husband to Switzerland and re-formed her group once again with U.K-based singers.

Between 1975 and 1977, Kerr recorded five gospel albums for Nashville-based Word Records. Her final album of new material was 1988’s In the Soul, on which she set the poetry of Walt Whitman to music. —Daryl Sanders

Lindsey Smith-Trostle, aka LST, aka Lulu Love

Cellist, teacher, beatmaker, string arranger, composer, session player

Lindsey Smith-Trostle was deeply engaged in Nashville music. She was a founding member of Athena Strings and Athena Piano Trio, as well as Swap Meet Symphony, a hip-hop band we created together. A proud native of Nashville, LST said she wanted to “revolutionize and modernize what classical music is,” and that’s exactly what she did.

She attended Hume-Fogg High School, Loyola University and Belmont University. As a professional cellist, she played with the Tennessee Philharmonic Orchestra, the Huntsville Symphony Orchestra, the Chattanooga Symphony & Opera and others. As a freelance session cellist, composer and beatmaker, she worked with Jack White, Yelawolf, Tanya Tucker, Kirk Franklin, Quiet Entertainer Orchestra and many more.

Lindsey passed away on Aug. 29, and is survived by her mother Wendy Smith and her father Greg Trostle. It had been a long time since we’d gotten to work together, but one of her closest friends, Lindy Donia Bennett, shared this on social media: “Lindsey loved others openly, honestly, and always put others before herself. She is one of the most loyal, compassionate, and gifted cellists, artists and songwriters among us and will be missed deeply. This hurts so badly, we love you. Beautiful Lindsey urged and encouraged others to be happy and live meaningful lives even when she went through struggles. In addition to her music career, she often dreamed of being a therapist and studying equine veterinary medicine.Thank you for calling me your sister for 18 years of friendship and loving and caring for so many others.” —Alex Davis-Smith, aka AL-D

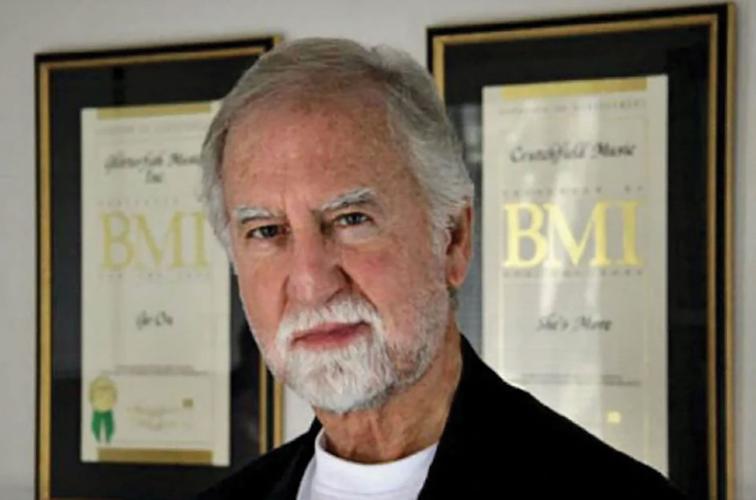

Jerry Crutchfield

Jerry Crutchfield

Songwriter, producer, executive

It’s not uncommon in Music City for people to successfully wear many hats over the course of a career. But few had careers as long, diverse and successful as that of Jerry Crutchfield, who died Jan. 11 at age 87. The Paducah, Ky., native’s first work on Music Row was as a backup singer on sessions for Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley. He turned down an offer to join The Jordanaires because he wanted to concentrate on his college studies. As a songwriter, he had songs recorded by country artists like Faron Young, Bobby Bare and Charley Pride, pop singers Brenda Lee, Ricky Nelson and Elvis Presley, and R&B performers Slim Harpo and Irma Thomas.

In the early 1960s, Crutchfield helped establish the Nashville publishing office of MCA, which he ran for 25 years while mentoring writers like Don Schlitz, Gary Burr and Russell Smith. Crutchfield also spent four years at the helm of the Nashville office of Capitol-Liberty Records. But it was as a record producer that Crutchfield might have made his biggest mark, winning multiple CMA awards for his work. Among the artists whose records he produced are Tammy Wynette, Glen Campbell, Dottie West, Lee Greenwood, Anne Murray and an amazing string of 20 top-10 hits for Tanya Tucker. One of the songwriters Crutchfield mentored along the way was Dave Loggins, whose 1974 pop smash “Please Come to Boston” Crutchfield also produced, a perfect example of the diverse experiences and skills he brought to everything he did. —Pete Finney

Dallas Frazier

Country songwriter, rock ’n’ roll master

I interviewed Dallas Frazier in 2008 after Buddy Miller, whom I talked to for a piece I was writing, mentioned him during the course of our conversation. It turned out I wasn’t familiar with Frazier’s story. Born in 1939 in Spiro, Okla., he moved as a child to California, where his family lived in boxcars and tents in labor camps in the 1940s. He started performing early, and he fashioned a couple of great rock ’n’ roll singles: “Alley Oop,” from 1957, and Charlie Rich’s epochal 1965 ode to Southern-fried hipsters, “Mohair Sam.” But I did know Frazier’s work — I had tuned into the message of Frazier and Earl Montgomery’s socialist-country masterpiece “California Cotton Fields” via a live version by Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris.

I interviewed Frazier at a Cracker Barrel restaurant near his home in Gallatin, Tenn., and he came across as an old-school hip person who name-checked jazz trombonist Jack Teagarden and ordered the vegetable plate. Alone or with longtime writing partner A.L. “Doodle” Owens, Frazier penned hits like “Elvira,” “There Goes My Everything” and “Hank and Lefty Raised My Country Soul.” For all his country success, which may have brought the kind of rewards that caused him to leave music for the church in 1976 — he told me in 2008 that he had “an over-scrupulous conscience” — I like to remember Frazier as a great rocker, which I think he aspired to be under what he termed the oppressive regime of Nashville country. Listen to his 1967 reading of rockabilly singer Ronnie Self’s “Home in My Hand.” Frazier’s version has the swagger — and the hard-won wisdom — of the best rock. He died in Gallatin on Jan. 14. He was 82. —Edd Hurt

Lois Curtis Shepherd

Singer, songwriter, Lower Broadway mainstay

An obituary shared by Robert’s Western World for Lois Curtis Shepherd — who died Oct. 18 at 98 years old — relays a story the honky-tonk fixture known to many as Miss Lois loved to tell. She spent her childhood years meandering to and from the Lower Broadway produce shop owned by the grandfather who raised her. One store on the block had black-and-white tiles in its window sill, and, the story goes, little Lois would pretend to play them like a piano.

She left Nashville for Florida, but returned in the early 1970s with John Shepherd, the aspiring singer-songwriter she would later marry. The couple spent the next 50 years as partners in love and music, with Lois writing many of the songs they played over the decades. In the 1980s, they played a key role in the revitalization of Lower Broadway, and as recently as 2020 they could be seen performing Sunday, Monday and Tuesday mornings at Robert’s. Fittingly, that was the site of her memorial service. The regulars gathered for songs and stories, to celebrate a life bookended by the sounds of country music on Lower Broad. —Steven Hale

Walter Riley King

Saxophonist, arranger, mentor

When you think of late, great blues legend B.B. King, what probably comes to mind first is his superb playing on his electric guitar Lucille, followed shortly by his powerful, soulful voice. But King also relied on a dynamite band to deliver a lush, full-bodied sonic experience to his fans. For more than three decades, he called on his nephew Walter Riley King for his prowess on the saxophone as well as his expertise as an arranger. Among other pieces, he was responsible for arranging the indelible “Stormy Monday” for the live show.

Walter Riley King was born in Lexington, Miss., and grew up in Bartlett, Tenn., near Memphis. He studied at Tennessee State University, where he performed with the mighty Aristocrat of Bands. He later worked with the marching bands at Goodlettsville High School and Pearl High School; his enduring passion for working with youth also took the spotlight when he moved with his family to Omaha, Neb., where he served as a guest conductor for the Omaha Youth Orchestras’ Youth Symphony. His extensive career included performing or recording with The Temptations, Gladys Knight, Dr. John, U2, Roy Clark, Joe Tex, Denise LaSalle and many more. At age 71, King died on July 19; services were held July 30 in Nashville. —Stephen Trageser

Laurie George

Punk rock fashion plate, tastemaker

Laurie George, whose work at Praxis International in the 1980s helped launch the careers of Jason and the Scorchers and The Georgia Satellites, passed away May 23 at age 59 after long living with COPD. A native of Waynesville, Mo., George was a prominent figure on the Nashville punk scene while still attending high school.

“Laurie was really into punk rock, and she had her finger on the pulse of the fashion side of all that,” says former Scorchers guitarist Warner Hodges. “But she also knew a lot about music, and that’s how she ended up at Praxis.” She joined the label as office manager shortly after graduating from Hillsboro High.

“She had more Nashville indie-rock cred than any of us,” says Kay Clary, one of the owners of Praxis along with Andy McLenon and the late Jack Emerson. “She looked like a jet-setting Parisian model but spoke with a honey-sweet Southern accent. She was intense and gave zero fucks but also had the most kind, empathetic heart you could imagine. Everyone loved Laurie George.” George left Praxis in the late ’80s after she began dating Satellites frontman Dan Baird. They married in 1995. —Daryl Sanders

Abraham Perry Mesaris

Punk rocker, veteran, friend

As frontman for the punk band El Escapado, Abraham Perry Mesaris was deeply rooted in the local punk rock community — a community that, upon Mesaris’ death, took to social media to share how he had affected their lives in a positive way.

Mesaris founded El Escapado with his friend K.D. Bell in 2015, and was frequently on the road, touring both in the U.S. and Europe. Just before Mesaris’ death, El Escapado had wrapped a 67-date cross-country tour. In a tribute following his death, Mesaris was remembered by not only his friends and loved ones, but a number of fans.

Mesari, also a U.S. Army veteran, is survived by his daughter Abella Charles-Mesaris and her mother Traci, as well as his mother and father, Patricia Steeley and Perry Todd Mesaris. Mesaris died July 22 at age 44. —Connor Daryani

Roland White

Bluegrass hero, supreme mandolin picker

Famed mandolin player and bluegrass singer Roland White died April 1 at age 83 following complications from a heart attack. A collaborator with legends like Bill Monroe and Lester Flatt, White first began playing music as a child alongside his siblings — famed guitarist Clarence White, banjo and double bassist Eric White Jr. and bassist Joanne White — while growing up in Maine and, later in his adolescence, in California. Originally called The Country Boys, their band eventually became The Kentucky Colonels; an outfit that inspired early practitioners of country-rock, the Colonels would release more than a dozen live and studio albums before disbanding for good in 1973 following Clarence’s death in an accident with a drunk driver.

As a picker for hire, White played as part of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys as well as Lester Flatt’s Nashville Grass. Later projects included the bluegrass band Country Gazette, The Nashville Bluegrass Band and The Roland White Band, which routinely appeared at the Station Inn in recent years. White’s long and storied career also included a string of solo albums, and he was inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Hall of Fame in 2018, the year he released A Tribute to The Kentucky Colonels, which features a murderers’ row of revered players across several generations. —Brittney McKenna

David Hagar

David Lee Hagar

Beloved live sound engineer

Working in live sound can be very tough. Your hours tend to be odd; if you’re part of a touring crew, the gig involves being away from your family for long stretches; not to mention the pressure of solving technical problems in real time, in front of an audience. For some individuals, however, this is the best life — David Hagar was one of them. For 23 years, the Nashville native worked for venerable firm Spectrum Sound, where producers of faith-based events, star clients like ELO and Styx and many more relied on him as a system tech, a monitor engineer (managing what the musicians hear onstage) and a front-of-house engineer (creating the mix for the audience).

On June 17, he died at age 44 of cancer, leaving behind his wife Danielle as well as an array of friends, family and colleagues whom he made to feel like friends and family. “Not only was Dave a superb audio engineer, but he was always eagerly helping out his co-workers or friends in any way he could,” reads a post on Spectrum’s Instagram. “Dave had a true servant heart and his cheerful attitude and friendly disposition made the world around him a little bit brighter.” —Stephen Trageser

Bil VornDick

Bil VornDick

Master of acoustic recording and production

Some key aspects of Nashville’s culture are only possible because people know how to make stellar recordings of acoustic instruments and how to bring out the best in people in a recording studio. Bil VornDick embodied all of that with an unfussy blend of refined skill, self-deprecating humor and deep kindness.

Born and raised in Virginia, he immersed himself in his local music scene as a young adult, playing guitar, writing songs and running sound at live events. None other than Chet Atkins convinced VornDick to move to Nashville with his wife Patricia and study in Belmont University’s nascent music industry program. Not long after he graduated in 1979, VornDick caught the attention of Marty Robbins, who hired him as the chief engineer at his studio. Over the four decades that followed, his work in what was dubbed “new acoustic music” — working with Béla Fleck, Alison Krauss, Jerry Douglas and others who were highly skilled in traditional techniques but hardly bound by them — set a high bar for engineering and production. He was sought after by bluegrass masters, traditional and mainstream country artists and Americana leading lights; he was nominated for more than 40 Grammys and notched up nine wins.

Despite the massive workload, VornDick put seemingly boundless energy into building up the music community through his involvement in educational programs, the Nashville chapter of the Audio Engineering Society and an array of charitable organizations. Any time you’d run into him, he had a kind word and a smile on his face. He died July 5, just five days after receiving a cancer diagnosis. He was 72. —Stephen Trageser

Remembering some of the irreplaceable Nashville figures we lost in 2022