When restaurateur Michael Gilbert moved to Nashville, he’d hear people talking about “meat-and-threes” and ask, “What’s that?” When someone explained that meat-and-threes are classic restaurants serving a menu where people can select a protein (the meat) and sides (the three), he said to himself, “Where I am from in South Carolina, we just call that lunch.”

“This is the food everyone in the South grew up on,” explains Benji Cook, owner of Wendell Smith’s Restaurant. “This is what moms and grandmas cooked.”

Call it a meat-and-three, or a “plate lunch,” or — like Gilbert — just call it lunch. The meat-and-three is an essential part of Nashville’s culinary legacy. Perhaps as much if not more so than hot chicken. The plate lunch exists elsewhere, of course. Since the end of World War II in particular, it has been a staple for dining out in the South. Sometimes it’s set up cafeteria-style, like at the recently closed Arnold’s Country Kitchen or the beloved and still-cookin’ Swett’s restaurant. Sometimes it is delivered through table service, like the now-closed Rotier’s or the still-cookin’ Elliston Place Soda Shop.

The way in which the food is delivered isn’t all that important. What’s important is the food itself, and the way in which the meat-and-three is an equalizer. No matter how much the New Nashville skyline changes, one thing remains the same: Everyone in town, from mayoral candidates to Grammy winners to college students, will wait for their turn for the comfort food that soothes their soul — be it fried chicken, neck bones or beef tips, with green beans, turnip greens or squash casserole.

Some thought the highly lamented closure of Nashville’s beloved Arnold’s — which followed the closings of Rotier’s, Dandgure’s Cafeteria, Katie’s Meat & Three and The Pie Wagon — sounded the death knell for the local meat-and-three. But those who run them say that’s not the case. That includes Gilbert, who eventually learned the proper terminology before opening MacHenry’s Meat & Three with chef Stephen Wilkerson in March 2020 as an outgrowth of their catering business. To paraphrase Mark Twain, the reports of the death of the meat-and-three have been greatly exaggerated.

Cook started washing dishes (“pearl diving,” as they call it) at his family’s Charlotte Avenue meat-and-three at age 12, more than four decades ago. He would get paid at the end of his shift and remembers heading to Phillips Toy Mart to spend his earnings. When Cook talks about Wendell Smith’s current restaurant regulars, he’s not talking about people who come in once a month or even once a week.

“The regulars I have come in twice a day,” Cook says. “I don’t know if they have a kitchen at home. Widows and bachelors, they come in because the food is great. As my dad used to say, ‘They don’t come in to see me.’ ”

To accommodate them, Cook roasts more than 500 pounds of beef a week. “This used to be a blue-collar neighborhood,” he says. “It’s changed, but there are still a lot of Old Nashvillians who are alive and well and eating.” Cook himself eats Wendell Smith’s fried chicken — made by dipping in egg and buttermilk — every day.

MacHenry’s

MacHenry’s Gilbert has regulars who stop in multiple times a week — unlike Wendell Smith’s, MacHenry’s is open for lunch only. Bailey & Cato, the meat-and-three that moved from Riverside Village in Inglewood to Madison a few years back, offers diners a punch card: Buy 12 plates and get the 13th free.

Do these customers become regulars because of the consistency and the predictability of the menus? Do they like knowing what to expect and when to expect it? Or is it because of the variety? They can build their own plate with a large number of permutations. At MacHenry’s, it’s six different proteins and 12 sides, plus specials.

While there are certain similarities to a meat-and-three menu, it isn’t exactly the same at each restaurant or even the same at each restaurant every day. The classic meat-and-three has a menu that rotates daily, so you know that if you want oxtails at Silver Sands Cafe in North Nashville, you need to go Thursday or Friday. Red meatloaf? That’s Tuesday at Bailey & Cato. But Gilbert finds that this model leads to complications in managing food waste. He didn’t want leftovers to sit in the refrigerator if that item was no longer on the daily menu, so at MacHenry’s, the menu changes quarterly.

Alphonso Anderson, owner of and chef at Big Al’s Deli in Salemtown, says his regulars know the daily lineup. But they also know if he has leftover meatloaf in the fridge, he’ll heat it up if asked, even if it isn’t on the menu that day.

Most meat-and-threes serve a steady diet of soul food, slow-cooked meats and sides, plus add-ons of classic Southern desserts, such as chess pie, banana pudding and frosted cakes. Sides are heavy on cooked and pickled vegetables, plus mashed potatoes, with the occasional sliced tomato as an option. The meat-and-three is one of few places in the world where both baked apples and mac-and-cheese count as vegetables. While the name persists, most restaurants let you choose a meat-and-one or a meat-and-two or even all sides, forgoing the meat altogether.

“You gotta have sweet tea and some variety of bread or biscuits there too,” adds Carole Bucy, Metro Nashville’s official Davidson County Historian. At Silver Sands Cafe, you can choose between hot-water cornbread or flat (buttermilk) cornbread.

As demographics in the city have shifted and people’s eating habits have changed, so too has there been some evolution of the meat-and-three menu, albeit incremental. While culinary historians suggest the decline of the Jewish deli is due to generational shifts in eating heathier, the meat-and-three seems to be adapting. Big Al’s Deli offers jalapeño-orange marmalade chicken, chipotle-raspberry chicken and chicken-fried banana pork loin. Anderson rarely makes mac-and-cheese, he says, preferring a healthier pineapple-cilantro rice. Many restaurants have added salmon options and other healthier dishes. On Thursdays, Bishop’s serves fish almondine as an option.

Traditionally, the vegetables at a meat-and-three were stewed with meat products, making even the all-sides option off-limits for vegans and vegetarians. At MacHenry’s there are sides made to satisfy vegans, vegetarians and those who avoid gluten. The fifth-best-selling item on the menu, Gilbert points out, is a large garden salad. Other places specialize in a twist on the traditional. Berry Hill’s Sunflower Cafe is designed to look and feel like a classic meat-and-three. As you slide your tray down the cafeteria line, you’ll note that everything on the menu is plant-based. Jamaicaway Restaurant in the Nashville Farmers Market includes a variety of tofu and seitan on the menu, as well as vegetable sides that are, in fact, vegetarian. None of Big Al’s vegetables contain pork, although some have chicken or turkey. Congregation Sherith Israel is hosting a kosher meat-and-three event next week. Other 21st-century adaptations are evident too. Puckett’s and MacHenry’s host live music. Many old-school meat-and-threes serve food in Styrofoam containers, even if you are dining in, but Gilbert uses compostable takeout containers.

No one knows for certain when or where the term “meat-and-three” first came into being. Some credit the late Hap Townes, whose Hap Townes Restaurant was a lunch tradition in one form or another from 1921 to 1985. Even the Southern Foodways Alliance, the source of all things related to culinary history in the South, doesn’t have a definitive answer.

“Our founder, Lynn Chandler, proclaimed himself ‘the king of meat-and-threes,’ ” says Jim Myers, Minister of Culture at Elliston Place Soda Shop. Chandler was one of the first to use the term in the promotion of his restaurant. In 1987, Chandler sold his Eighth Avenue South restaurant to his employee Jack Arnold. That restaurant became Arnold’s Country Kitchen, further cementing Chandler’s role in birthing the meat-and-three that symbolizes Nashville’s dining essence.

As suggested by its alternate plate-lunch name, some meat-and-threes are open for lunch, weekdays only. Gilbert loves this, because it allows him to balance owning a restaurant and a catering company with spending time with his family. “A lot of restaurant people are nocturnal,” he says, referring to the typical kitchen job that has employees working past midnight. “I get to be a husband and a dad too.”

Others, like Wendell Smith’s, are open longer hours, serving hot breakfasts to the before-work crowd and hot dinner before they head home. Jay’s Family Restaurant, Puckett’s and Ramzy’s Meat & Three are open seven days a week. Barbara’s Home Cooking in Franklin is open on Sundays. Many meat-and-threes, including Swett’s, Puckett’s, MacHenry’s and Big Al’s, offer catering as well.

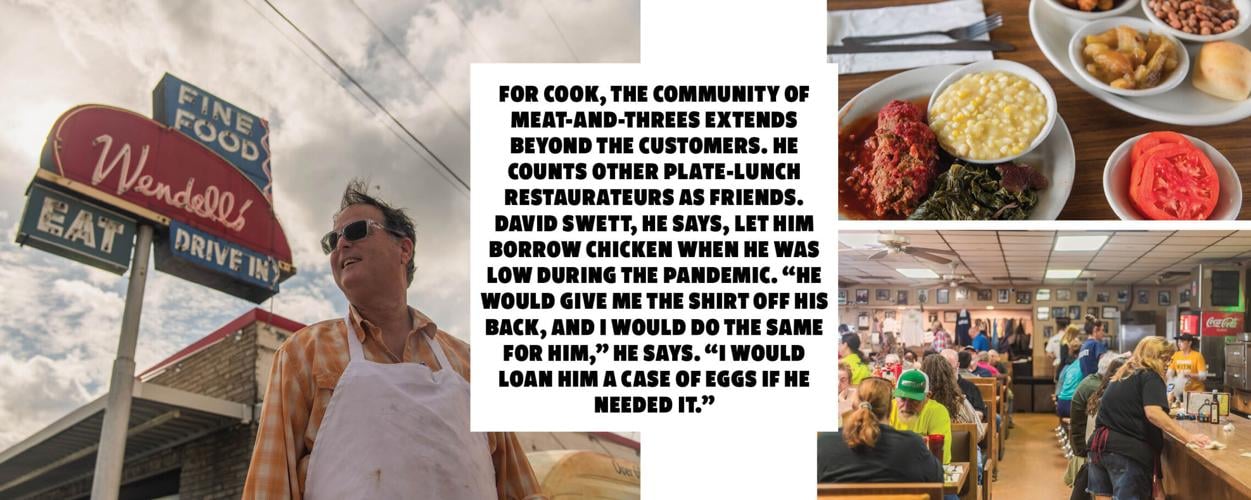

For Cook, the community of meat-and-threes extends beyond the customers. He counts other plate-lunch restaurateurs as friends. David Swett, he says, let him borrow chicken when he was low during the pandemic. “He would give me the shirt off his back, and I would do the same for him,” he says. “I would loan him a case of eggs if he needed it.” (That’s saying something, given the current pricing and demand for eggs.)

Silver Sands Cafe reliably has lines of locals waiting for their plates. For more than 70 years, the family-owned restaurant has been a community staple and a favorite of other area chefs who want to eat good food and show off good food to their friends coming in from out of town. When Silver Sands suffered roof damage after the March 2020 tornado, local chefs including City House’s Tandy Wilson and Sean Brock helped raise funds to keep Silver Sands cooking.

For all the loyalty, it’s not easy running a restaurant. Even without an egg shortage, a pandemic or a tornado, margins are slim, and labor is tight. That said, there’s one expense Cook refuses to skimp on: neon repair. The Wendell Smith’s Restaurant signage is some of the city’s best and most iconic neon, and Cook does his best to keep it in working order — though he laments that some of the blue is currently not functional. While the signage has come to symbolize the West Side establishment, Cook says his grandfather originally repurposed the sign from a neighboring shoe store called Wendell’s.

“That is our baby,” Cook says. “I treasure my neon, for sure. If I ever closed the restaurant, I would cut that down and take it to my house.” But rest easy! Wendell Smith’s is in no danger of closing. One of Cook’s sons is in training to take over the business, and Cook is thrilled to have a succession plan.

“Meat-and-threes are an important part of Nashville tourism,” historian Bucy says. “People come here for a certain type of culinary experience, and it is sort of unique.”

Indeed, while Wendell Smith’s and others draw folks from their neighborhoods on a regular basis, others rely on out-of-towners to keep the steam tables hot. Anderson says the majority of his business — aside from his popular catering business — comes from visitors rather than those from the surrounding Salemtown and Germantown areas. “It is not unusual for me to get customers who tell me that they came to see me from Canada or Australia, from all over the world.”

To continue the meat-and-three education, the Soda Shop’s Myers is in the process of starting a Meat-and-Three Alliance, with plans for a passport to be released later this year. Once diners have all the pages stamped in the enviably grease-stained book, they’ll get some kind of prize, maybe a T-shirt. Myers hopes the organization will draw attention to Nashville’s beloved comfort food, much like former Mayor Bill Purcell did with the Music City Hot Chicken Festival.

But it all boils down to this, says Myers, who gives everyone an excuse to go out to lunch as often as possible: “You gotta eat it, to save it.”

Nashville’s Meat-and-Threes

Looking to build your own plate? Here’s a list of nearly two dozen standout meat-and-threes in the greater Nashville area.

Most meat-and-threes are focused, without much else on the menu. For the purposes of this list, we’ve also included restaurants with more extensive offerings, as long as choose-your-own-plate is an essential part of the offerings.

55 South, 7031 Executive Center Drive, Brentwood (and other locations)

Bailey & Cato, 1130 Gallatin Pike S., Madison

Barbara’s Home Cooking, 1232 Old Hillsboro Road, Franklin

Belle Meade Meat and Three, 110 Leake Ave. (Note: The restaurant is located at the Belle Meade Historic Site, formerly known as the Belle Meade Plantation. Some readers may not feel comfortable casually dining at a site built by enslaved people.)

Big Al’s Deli, 1828 Fourth Ave. N.

Bishop’s Meat & Three, 3065 Mallory Lane, Franklin

City Cafe East, 1455 Lebanon Pike

Dalton’s Grill Bellevue, 79061 Highway 70 S.

Doll’s Family Cafe, 2501 Gallatin Ave.

Elliston Place Soda Shop, 2105 Elliston Place

Jay’s Family Restaurant, 3037 Dickerson Pike

Jamaicaway Restaurant, 900 Rosa L. Parks Blvd.

Lil Cee’s, 605 Douglas Ave.

MacHenry’s Meat & Three, 581 Murfreesboro Pike

Monell’s, 1235 Sixth Ave. N.

Puckett’s Restaurant, 500 Church St. (and other locations)

Ramzy’s Meat & Three, 306 Thompson Lane

Silver Sands Cafe, 937 Locklayer St.

Simply Southern Cafe, 1749 Highway 41, Pelham

Sunflower Cafe, 2834 Azalea Place (Note: This plant-based restaurant refers to itself as a “beet-and-three.”)

Swett’s Restaurant, 2725 Clifton Ave.

Wendell Smith’s Restaurant, 407 53rd Ave. N.

Pictured: Swett's