This article is part of a two-part cover story on LeXander Bryant's current show at the Frist Art Museum. See also: "Memories of a Native Son: LeXander Bryant’s Solo Exhibition Forget Me Nots Resists the Act of Forgetting."

LeXander Bryant’s exhibition Forget Me Nots is the Nashville artist’s first solo museum show, but it isn’t the first time he’s had work at the Frist Art Museum. He was part of the group show Murals of North Nashville Now in 2019, and before that he was involved in the 2017 exhibit Nick Cave: Feat.

Forget Me Nots is a triumph. It includes three galleries of the 32-year-old’s artwork — one focuses on Bryant’s photo-based practice, and another contextualizes his wheatpaste posters with an installation and documentary set to music by frequent collaborator Mike Floss. The third gallery features a monolithic concrete slab covered in plastic forget-me-not flowers peeking through cracks. Bryant joined the Scene for a walk through the entire exhibition. We began at the cluster of photographs Bryant calls the “memory wall.”

“I call it the ‘memory wall’ because they all reference some moment, some experience, some idea that I can relate back to my childhood,” says Bryant. “I feel like they’re small moments that you don’t really pay attention to, but over the course of time, they kind of make up a larger picture. Every one has a different story. Some are documentary style, others are in a studio setting. They all relate to a moment or idea.”

Read our interview below.

I see a lot of contrast between city and country, but also cars, bikes, subways — ways to get out of where you’re from or move to somewhere else.

That’s right. The New York taxi cab, for instance — that one just tells the story of this country boy who grows up thinking that everything he needs, everything he wants, is in the big city. And that I don’t have the resources in a small town to survive, or to make something of myself that I can be proud of. The shoes that hang on the power line — it’s this love for city life, and the desire to live in a big city when you grow up in a small town.

The one with the eyes — “Neighborhood Surveillance’’ — is interesting. You think of a photographer as someone who is being the voyeur, but these are you capturing people looking back at you. There’s an idea of being looked at even as you’re taking the photos.

That’s a great point, because a lot of this is based on self-reflection. I like to say that my work serves as a kind of self-help book for me. It’s a moment to reflect and sit back and think about what you’ve captured, and think about what your mindset was at the time of the photo. I feel like looking at the eyes is almost like looking at myself. With any of these subjects, I see a piece of myself. Even if I’m seeing a nostalgic version of my parents, or myself in my childhood, my cousins and uncles — we have a similar theme in our lives of trying to make it, family community supporting each other. I think you can feel that through the work.

There’s also a lot of religious imagery here.

The church has a strong influence on who I am. I mean, I don’t consider myself religious today, but I would be lying to myself if I didn’t acknowledge the influence of Southern religion — being at church as a child, hearing the music, seeing the way people love each other, the way we support each other, the way we dress when we come to church, the things we do after church. Family, Southern Black tradition and community — it’s all the same thing.

This main image, “The Most Known, Unknown,” is out of focus, almost like he needs you to stand away from him a little to really see him.

It wasn’t captured blurry on purpose — it was more of a misfire. But out of all the photos in this sequence, it stood out the most. The story I was able to apply to it is that this is the relationship that I have always had with religion — you see this figure and it’s powerful, but you don’t always know a lot about it. You don’t trust it. So I titled this piece “The Most Known, Unknown.” I think that’s the relationship that a lot of people have with religion with whatever deity you choose. It’s taboo to talk about, especially in the South, especially in a Black family that loves Jesus.

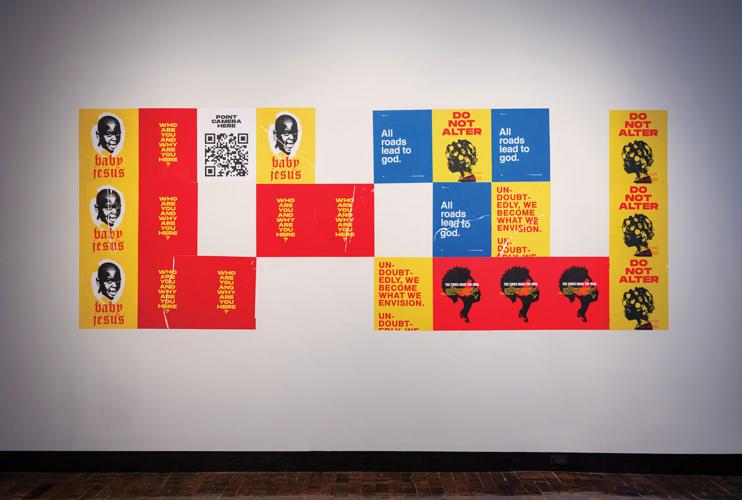

I love how the wheatpaste posters are installed. Street art in a gallery setting is so hard to get right, and I like how it’s fucked-up on purpose. The design is really simple. It reminds me of the overlap between street art and advertising, and how graffiti is really just advertising yourself.

The wheatpaste work was inspired by corporate advertising — those big posters for Lil Wayne and Snoop Dogg and Kendrick Lamar that I was seeing all over the streets in L.A. I just feel like, man, it’s hard not to see that. So how can I flip that? How can I create something that’s just as powerful, just as impactful — and just as hard not to notice.

So your inspiration was wheatpaste ads, not wheatpaste graffiti?

Right. And once I figured out what it was, I did research into all these artists who were using it — Shepard Fairey and everybody. But they don’t do it like I do it, and I couldn’t find anyone Black doing it. That’s usually the issue — whenever you’re looking up wheatpaste, or even photography, or sculpture. It’s always good to see someone who looks like you. That’s the inspiration for a lot of my work — representation, and making sure we have a seat at the table. And pretty soon, we own the table.

And people like Shepard Fairey might be able to put up the work with relatively little fear. Worst case, the cops will run them off, so the stakes are lower.

That’s another reason I wanted to get into it — the stakes are lower across the board, because it’s posters. It’s not as permanent as graffiti. I don’t see it as vandalism.

Right, but I was thinking that maybe the stakes were lower because he’s a white man with a certain level of fame. So there’s no real danger.

Right, and they’re not threatened by his message either. I think that’s where a lot of it comes from — being willing to put these bold statements up.

That makes me think about this baby Jesus poster. Can you tell me about it?

That might be the first wheatpaste poster that I ever designed. It’s one of my cousins — Julian, from Walker Springs, Ala. I took it in my uncle’s front yard. Having it here is a good feeling, because now he gets to see how art can be used for good, and how you can use it to change your life, and just where you can take it. It’s a firsthand experience. Like, “Wow, he took my photo, and now I’m in a museum.” He can tell that story.

Why did you decide to associate him with Jesus?

I just felt like he had this strong Black presence in the photo. Even as a child.

The seriousness in that eyebrow!

And he still looks like that! He still has a very composed way about him, he looks comfortable. The reason I included “Baby Jesus” is just tying back to Southern spirituality and my roots. You never see a version of Jesus that looks like you. No matter where you grow up in the South, it’s usually the same version of Jesus that you see. So I wanted to create one that looked like me, that was created in my likeness, and that other people like me can relate to.

Do you create work intentionally for a primarily Black audience?

I don’t think it’s my intention, but based on the work, that’s who’s going to be seeing it. I don’t ever want it to feel watered-down. I don’t want to be politically correct with my work. I want it to be like a conversation you might have with your friends about how you see the world and what your ideas are and where you want things to go, the problems that you’re having. Everyday talking.

It reminds me of something I saw on social media where a group of Black women held up pictures of their sons and asked, “At what age did my son become a threat to you? Was it at this age? Or at this age?” Because I see these posters and think about how this is a sweet person who I’m ready to care about.

For sure, and the image — that same lovely spirit and charisma — it never really goes anywhere. But what does change is my appearance as a Black man. As I get older, my appearance changes. And so if you only think of what you see on TV — that’s where the fear comes from.

Right, but that wasn’t your intention with this?

No, not at all. It’s a good point though.

And these posters — “Who are you and why are you here?” Are you directing that question toward gentrification in North Nashville?

No, it’s just a personal question. I think it’s just a good question to ask. It gives clarity about who you have around you.

I think maybe it’s a byproduct of using the medium of advertising, where the message is always directed at the individual, because I see this as an almost accusatory statement, and I’m not sure that a different medium would have so many divergent interpretations.

I think that’s the beauty of it — it’s direct, but it’s also loose enough to where everyone has their own interpretation of it. That’s what it’s about — just making you stop and think.

The way the video includes documentation of the kids putting up the wheatpaste poster that’s on the “memory wall” really connects the story in these rooms.

It was the kids that lived on my street that were the kids who helped me put up the eyes. Even before COVID, they would just be out in the streets playing basketball, baseball, riding bikes. And I was always engaged with them, just talking to them or playing basketball with them. So when I shot the picture, I told them I would pay them to help me. I wanted them to be involved in the process and see how it works, and I wanted to pay them so they would be like, “Whatever he’s doing, he’s making money off of it, so let’s pay attention.” They were all impressionable ages — 9 or 11 to 17. And they really listened. So I knew they would be great for the project, and we set a date for it. I even had their moms’ numbers; their parents trusted me. And we went out one night, it was super cold, and we put it up, and documented the whole thing. I just wanted them to see that this is what I do every day.

Did you mix the wheatpaste yourself?

I let the kids mix it, actually. I wanted to show them how to mix it, and what the process would be like. And when we did it, the sun was going down, and it was cold — it was January last year, if I’m not mistaken. And the sun was going down as we’re putting up the first few panels. So by the time we finish, it’s already dark. I let the kids do most of it, just so they could really see what it all feels like.

We’re talking about your intended audience for a lot of this work, and it seems like a lot of the intended audience is kids, or young people. You seem aware that what you’re doing is important because people are watching you. And it’s also smart to have kids involved because it makes the wheatpaste seem above-board.

People loved it. People were literally stopping by to say, “We love what you’re doing! Keep it up!” And that’s what I want — I want people to see that we don’t have to depend on people to come and do all this fake charity stuff. We can just kind of build this ecosystem amongst ourselves and we can have a good time.

So I wouldn’t say the work is intentionally geared to kids as the audience, but a lot of it is about me reflecting, and that innocence you have as a youth, how impressionable you are — that’s kind of when you figure out who you want to be. Even if you’re too afraid to voice it, to say it out loud, you know what you want to be, and you know how you want to live your life. Sometimes the circumstances don’t really work out in your favor. So if there’s an age when I want to have an impact on someone, it’s definitely at a young age.

And you called this piece “Neighborhood Surveillance,” like this kid is watching the whole neighborhood.

It’s funny because I didn’t name it that because of the eyes. I named it that because — at this intersection, on every corner there are police cameras. I just felt like everyone was watching, even when you’re just trying to get home, you see these cameras. I can’t even walk to the end of the street with my son without knowing that someone is watching.

And the double meaning there — that he’s watching himself being watched. He sees himself as someone who needs to be watched, or has to be watched, and also someone who has to watch.

Yes. The title of the show was originally going to be Things We Can’t See. But there was a day that I was just sitting with my son, and we were listening to music, and Patrice Rushen came on. She’s an ’80s pianist, but she’s also an R&B singer. And she has a song titled “Forget Me Nots.” It’s a cool song, and every time I hear it, it makes me feel good. And I just knew when I heard it that that needed to be the title. When I heard it, and my son was right there, he asked, “What song is this?” He was so curious about what the song was. It speaks to memories and moments that don’t need to be forgotten. Or more so, events that relate back, and how you can’t forget them. The small things that happen as a child, the good and the bad. How eventually it just makes you who you are.

LeXander Bryant

The Nashville artist’s work is on display at the Frist through May 1