From left: XPayne, LeXander Bryant, doughjoe, Sensei, Brandon Donahue, Elisheba Israel Mrozik, woke3, Courtney Adair Johnson, Omari Booker, Marlos E’van

Despite being the frequent site of systemic injustice, North Nashville has long been an area of transformational change. The students who led the Nashville civil rights movement were educated in the area’s four historically black colleges and universities, and trained in nonviolence in the neighborhood’s church basements. Starting in the 1930s, the practice known as redlining made it impossible for the people in the community to accumulate wealth through homeownership, and deterred federal, state and city entities from investing in the area. Black North Nashvillians persevered, creating a thriving corridor of cultural and economic life on Jefferson Street. In the late ’60s, the construction of Interstate 40 disemboweled the neighborhood, displacing families and shuttering black-owned businesses.

Today the neighborhood remains in flux. The zip code 37208 has one of the country’s highest rates of incarceration among people born between 1980 and 1986, and the black population is in decline. “The influx of developers and home-flippers has acted as a new interstate,” the Scene wrote last year, “chewing up the vulnerable and putting immense pressure on everyone else.”

Despite these external forces, hope stays alive in North Nashville, through grassroots organizations that disrupt violence and mentor kids, neighborhood groups that lead bike rides and host street festivals, and cultural events like the monthly Jefferson Street Art Crawl and annual African Street Festival. And though new urban development is changing the face of the neighborhood, artists are using street art to reflect the social issues unique to their community and articulate a hopeful vision of the future.

The Frist Art Museum is shining a light on some of the neighborhood’s artists with Murals of North Nashville Now, an exhibition of eight new works that stretches through the long hallway of the Conte Community Arts Gallery. All of the exhibition’s featured artists live or work in the neighborhood, or have studied at Fisk or Tennessee State, and their 8-by-10-foot murals are cathartic expressions of the neighborhood’s past, present and future. Frist curator Katie Delmez says the exhibition explores what role the arts play in urban redevelopment and the expression of neighborhood identity — two things that are often at odds.

“I think it’s important to bring that story to the Frist, because a lot of people — both newcomers and native Nashvillians — aren’t always aware of what has happened in North Nashville historically, and what’s happening now,” says Delmez. “I’m hoping that as people walk through the Community Arts Gallery … they can’t help but see these works and be aware of the great talent that’s here in Nashville.”

North Nashville artists are staking a claim in their neighborhood creatively and collectively — a force of vibrant resistance against displacement. —EC

“Forever,” Norf Art Collective.

Norf Art Collective

Norf Art Collective

Norf Art Collective uses the city as its canvas — from the walls of Jefferson Street businesses to a tribute to female activists on Nolensville Road, the group of artists stays busy. Though Norf is undefined in its membership, four artists collaborate as the group’s core: painters doughjoe, Woke3 and ArJae (aka Sensi), as well as photographer Keep3. Their work incorporates elements of graffiti, fine art and Afrofuturism, with stylistic echoes of their teachers — local artists like Michael McBride, Samuel Dunson, James Threalkill and Thaxton Waters. Norf’s work is rooted in black identity and history. The group doesn’t limit its reach to North Nashville, but its ties to the neighborhood keep the Norf members grounded. The group stays active in the community, leading art classes with kids, collaborating with neighborhood advocates at events like the African Street Festival and Open Streets, and helping organize the monthly Jefferson Street Art Crawl.

“Forever” and “Fly”

Norf’s two murals at the Frist carry over characters from the group’s 1,000-square-foot stunner “Family Matters,” located on Clarksville Pike, in which two children march beside Nashville civil rights leaders. In “Fly” and “Forever,” a new generation of activists takes off. The children are older — no longer towing a teddy bear or sucking a pacifier. “Forever” shows a girl mid-leap. Ahead of her is Fisk University’s Jubilee Hall, and stacked nearby are books, a promising education, the world at her feet. “Fly” shows a boy in flight, soaring above a chessboard street and urban development. A trio of the boy’s ancestors burst from a passionflower behind him. In both murals, the boy and girl stand out against monochromatic backgrounds that are packed full of symbolic images. We see that North Nashville is multifaceted — it is history and hardship, progress and hope. —EC

“Fly,” Norf Art Collective.

“Rest in Peace,” Brandon Donahue.

Brandon Donahue

Brandon Donahue

Brandon Donahue assembles found objects — among them hubcaps, deflated basketballs, discarded toilet seats and chicken bones — to create a body of work that’s influenced by folk art and hip-hop alike. Donahue’s first love was airbrushing, and growing up in Memphis, he painted the jackets, sneakers and skateboards of his friends, emblazoning them with their names and tags — and sometimes, the dates of friends’ deaths. As an undergraduate, he attended Tennessee State University, where he worked as an assistant professor from 2014-2019. Donahue just moved to Washington, D.C., where he’ll be artist-in-residence at the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland.

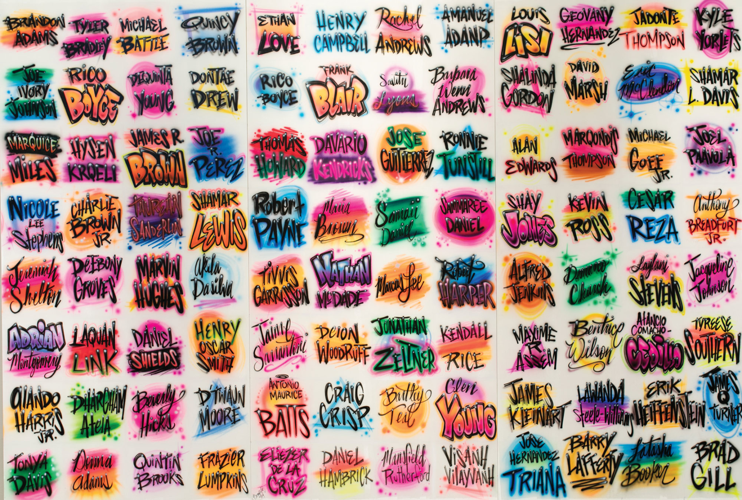

“Rest in Peace”

Like much of Donahue’s work, “Rest in Peace” couches serious subject matter in a playful aesthetic. The artist puts his airbrush skills to use here, painting people’s first and last names in bold, fluorescent colors like those you might see on T-shirts at a Daytona Beach boardwalk, but with a repetition that’s reminiscent of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Up close, Frist visitors may recognize some of these names — like that of Daniel Hambrick, the 25-year-old Nashville man who was shot in the back and killed by an MNPD police officer last year. Other names will be familiar: Taurean Sanderlin, Joe Perez, DeEbony Groves and Akilah DaSilva are the victims of Travis Reinking, the man who opened fire in a Nashville Waffle House last year. Donahue airbrushed the names of 96 Nashvillians who were killed by gun violence in 2018 and 2019. He researched each person, each death, and his tribute to them is a chilling reminder of the scope of gun violence in Nashville. —EC

“Opportunity Cost,” LeXander Bryant.

LeXander Bryant

LeXander Bryant

If you think LeXander Bryant’s wheat-paste-on-panel mural resembles the graphic ads that are often found along city streets, you might be surprised to learn that the artist grew up in the country. “Dirt roads, pine trees,” he tells the Scene as a kind of shorthand for his small-town upbringing in Jackson, Ala., a town an hour north of Mobile with a population of about 5,000. He moved to Huntsville for college, and eventually landed in Nashville in 2014. These days, Bryant is primarily a photographer, but his wide-ranging visual style is influenced by the multimedia culture of advertising, as well as a deeply felt belief that artists can speak for an otherwise unheard community.

“Opportunity Co$t”

“Opportunity Co$t” is the most visually direct mural of the North Nashville Now exhibit. It features a young man staring straight ahead, the politically charged slogan “WE WANT YOU” beaming from beneath his stoic face. Like Uncle Sam, Bryant is in the business of enlisting recruits — but in this case, he’s looking for African American professionals, not soldiers. “I think that wealth and financial independence is very important in black communities,” Bryant tells the Scene. “When you ride up Jefferson, you see a lot of black businesses, but they’re funeral homes, car washes, churches. We also need architects, teachers, data analysts.” He borrows visual queues from advertising — his bold red-and-yellow palette borrowed from fast-food restaurants and check-cashing spots. “I’ve always been a nerd for marketing, advertisement, propaganda,” Bryant says. “There’s this idea that the media controls the narrative — I wanted to create my own version of that.” Panels featuring the phrase “TRANSFORMING MINDS” bookend Bryant’s mural with a vertigo-inducing swirl. That’s the artist’s goal: to use his art to infiltrate the world, twist its inhabitants around, and reorient them. —LHH

XPayne

XPayne

The art of XPayne — the nom de graffeur of Xavier Payne — references everything from Grace Jones to Andy Warhol to Living Single, but is always unmistakably the artist’s own. A Watkins graduate, XPayne uses a style that is flat and graphic, sharp and comical, and always strengthened by specificity — Payne is an astute observer of pop culture, which often places importance on the most mundane aspects of everyday life. Payne has lived in Nashville since he was 5, and growing up he relied on his older sister, who was a teenager in the 1990s, to inform his worldview. He filled his mental Rolodex with work by John Singleton and Matt Groening from an early age.

“Adaptation”

XPayne’s “Adaptation” mural includes African American caricature-like versions of Mickey Mouse and Batman, a swirl of a green dragon encircling them, and a burning, off-kilter cityscape. Underneath those pop-cultural references, Payne has a familiar story to tell: a stranger is ripped from the world he loves, dropped into chaos, and enlisted to combat evil capitalist forces. It’s an epic piece, and luckily Payne has the chops to make it sing. “The idea,” Payne explains in an email to the Scene, “is that Mickey is nervous and scared about combat in the first panel, but has adjusted to his environment by engaging in this battle with the dragon.” The city is contemporary and American, but the weaponry evokes 19th-century Africa. “While the style of the shield is inspired by Zulu shields of Southern Africa, the spear is intentionally broken to use like a sword to fight face to face. This comes from the military tactics of Chief Shaka Zulu, one of my earliest introductions to black male masculinity in pop culture.” —LHH

“Unmask ‘Em,” Elisheba Israel Mrozik.

Elisheba Israel Mrozik

Elisheba Israel Mrozik

Elisheba Israel Mrozik came to Nashville after receiving a fine arts degree from Memphis College of Art. Her work often depicts black women as matriarchs, goddesses and warriors, and is frequently charged with messaging about systemic inequity, racism and sexism. Mrozik opened One Drop Ink Tattoo Parlour and Gallery in a one-room studio above the NAACP office on Jefferson Street in 2011. She wanted to create a tattoo shop that served the community, with artists who were skilled at tattooing on brown skin. The shop is still located on Jefferson Street, but in an expanded space, and it’s become a creative hub in the neighborhood as well as a stop on the Jefferson Street Art Crawl.

“Unmask ’Em”

Mrozik says participating in the exhibition gives her the chance to reveal an honest, from-the-source message of dissent. Dissent in visual art is nothing new. But as a black woman, Mrozik hasn’t felt welcome to voice her own dissent in arts institutions. “Unmask ’Em” borrows from Michelangelo’s “Pietà,” centering a black woman as the Virgin Mary or mother figure. In one arm, she cradles a cherubic baby. In the other, a slain man. They’re surrounded by other figures with symbolic meaning — one in a red hood points an accusatory finger at the trio, blaming them for their own hardship; another burns the pages of a history book. Behind them, African ancestors threaten to unmask these threatening figures. The mother is unflappable, her blank eyes reveal nothing about the emotional turmoil she must be feeling. She has the demeanor of a woman who knows justice will eventually be served. —EC

“The Writing’s on the Walls,” Omari Booker.

Omari Booker

Omari Booker

Omari Booker works as a framer and gallery curator at Woodcuts Gallery & Framing, a 30-year-old institution that has long been a haven for black artists. From this Jefferson Street vantage point, Booker has seen the physical transformation of the neighborhood up close. He paints with a rich palette that infuses his subjects with warmth, particularly in his 2017 series I Live Here. It’s a collection of portraits of people living and working on both sides of Rosa L. Parks Boulevard: in the Germantown neighborhood, which is home to the restaurants of award-winning chefs, high-end boutiques and luxury lofts, and along the Jefferson Street corridor, which is home to Fisk University, black-owned businesses like Woodcuts and Ooh Wee Bar-B-Q, and a rapidly changing housing landscape. Booker renders no judgment in the portraits; he doesn’t indicate where he met the subjects. They affirm the existence of people from both sides of the boulevard.

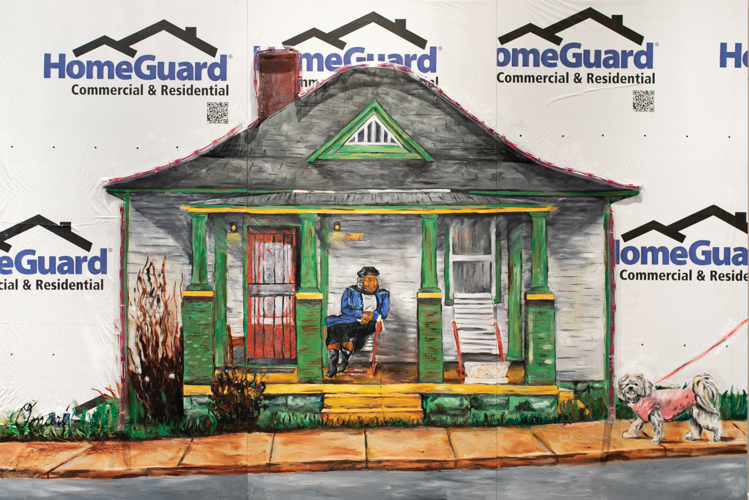

“The Writing’s on the Walls”

Booker’s mural depicts the home of Eloise Freeman on the 2500 block of Jefferson Street. The home has been in the Freeman family for nearly 100 years. When I-40 was built in the late ’60s, the family lost their front yard, but they were lucky — hundreds of houses and businesses along the corridor were demolished. Today, the black population of the 37208 zip code is rapidly declining. In the painting, the house wrap covering the Freeman home draws attention to the encroaching development, and a red wire mounted around the house references redlining. As the property value of the neighborhood rises, who gets to live there? “The Writing’s on the Walls” is an uneasy portrait of a neighborhood in flux. —EC

“Where we were, Where we are, Where we are going,” Nuveen Barwari, Marlos E’van, and Courtney Adair Johnson, with Opportunity NOW and International Teen Outreach Program participants.

McGruder Social Practice Artist Residency

From left: Nuveen Barwari, Marlos E'van, Courtney Adair Johnson

Teaching artists at Oasis Center and the McGruder Social Practice Artist Residency play big roles in their communities. Both programs use art and creativity as a means to engage Nashvillians at an extremely impressionable time — their teenage years. For this project, M-SPAR’s Nuveen Barwari, Courtney Adair Johnson and Marlos E’van asked a group of participants from McGruder’s Opportunity NOW internship and Oasis Center’s International Teen Outreach Program to consider their place in Nashville’s cultural landscape. The talented young artists who helped create the collaborative piece are Jesua Aguilar, Saira Aguilar, Kam’Ron Allen, Melodi Leiva Arreola, Ashanti J. Chatman, Isaiah M. Crouch, Nadia Cruz, Kimora Cunningham, Navaeh Flowers, Joy Ibrahim, Maximos Ibrahim, Makyia L. Lacy, Mainer Maldenado, Randy Mancia, Angel McElrath, Aryan Phuyal and Samari LaSha Sims.

“Where We Were, Where We Are, Where We Are Going”

The three panels in the collaborative mural by Nashville’s youth work like a timeline of the city. To create the multimedia piece, McGruder’s teaching artists led tours of important North Nashville spots, including the ephemera-laden music studio and museum Jefferson Street Sound and the storied art galleries of Fisk University. In the left panel, a bruised and tattered black figure is crying, and quotes about civil rights and racism litter the cartographical composition. On the right panel, people with smiling faces stand together in a kind of human chain surrounded by flags representing America, Brazil and Mexico. If you’ve ever been curious about what Nashville’s youth want from their city, take note: Across the panel in bold letters, they have written, “We are the future generation” and “Keep Nashville diverse.” —LHH

Detail from “Adaptation” by XPayne