“The Most Known, Unknown,” LeXander Bryant

This article is part of a two-part cover story on LeXander Bryant's current show at the Frist Art Museum. See also: "I Want You to Remember: LeXander Bryant on Memory, Childhood, God and Everything."

Memories fade. This is a truism. We find, by imperceptible degrees, the edges of what we can remember about our early years disintegrating like brittle paper. Sometimes the more we try to probe our minds for details, the more elusive those particulars become.

But memories can also take on new acuities. We buy perfume or cologne because it brings us back to a bed, or a hand, or a bench. Spurred on by the smell of leather, we remember names and faces. Fuller scenes of sunsets, valleys, malls light up the cinemas of our minds. In the Old Testament, Lot’s wife looked back to remember a valley where she had eaten and loved. And for her sin of refusing to forget, she was turned into a pillar of salt. Lest we find ourselves on the wrong side of that story, it would do us Americans good to recall that we are no better than the salt-making Divine. For all of our private acts of reminiscence, we often criticize revisiting the sweetness of the past; we call this nostalgia, and have instilled in it a negative connotation.

LeXander Bryant’s debut solo museum exhibition, Forget Me Nots — currently on display at the Frist’s Gordon Contemporary Artists Project Gallery — is a visual and ethical resistance to the act of forgetting. On display through May 1, the multimedia show features Bryant’s photography, wheatpaste posters, a concrete sculpture centerpiece and a documentary. With this multifaceted approach, Bryant hopes to enhance the visual identity of the South — a noble and necessary effort, since Black people are largely being forgotten amid the boom of the New South. Bryant’s creative process is all about feeling, a spiritual act of creation, investing his art with the communal laughter, pain and luxury that he remembers.

In the photography room, a full-scale image demands immediate attention. This is not due to its crisp detail, but because it is entirely blurred. “The Most Known, Unknown” depicts a Black man against a cinder-block wall. But you can’t appreciate this figure up close. You must back up, give him space. And then, the texture of his Aegean-blue fedora can be absorbed. Around his neck is a dagger of a cross, representing, it seems, both piety and protection. The structure of the photograph evokes the paintings of Kerry James Marshall, who often renders his Black subjects as shadow people, as if hollowed out by American fear.

The uniform blurriness of the photograph is disconcerting on two levels. White people socialized into white supremacy may experience a visceral fright at this enigma. Without clarity of features, they cannot assess the potential threat level. And for Black viewers, we feel fear for him because we know the corporal danger of being mysterious in white America. The Most Known — which is also to say, “the devil you think you know,” the devil about which you have written your miles of monographs, conducted your multitude of studies — has rendered himself unknown; the blurriness is an act of defiance. A removal of labels. It is to say, “You won’t see me, until perhaps by some divine act, your vision is righted” — like in the New Testament’s Book of Mark, when Christ spits into the eyes of a man three times before he finally stops seeing “men as trees.” There are times, in the inferno of national violence, in which Black Americans must want to ask their white counterparts, “Why is it that you see people as trees, to use or cut down or campaign for or save?”

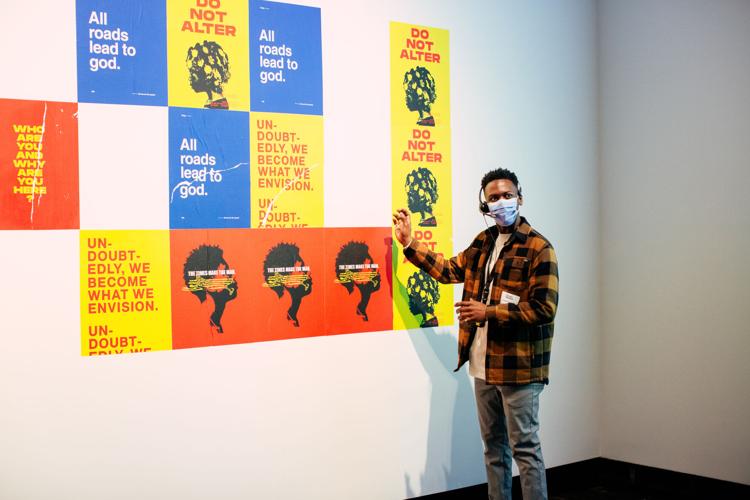

This line of questioning follows in Bryant’s room of wheatpaste posters. Emblazoned in red and yellow, the posters conjure up a dilapidated McDonald’s in the hood. It is quixotic and clownish, as though we are asking each other one of the poster’s questions over hamburgers and fries: “Who are you and why are you here?” reads one. In Nashville, Black folks are asking this of the white people who jog through our neighborhoods. In America, white people are asking this of whomever they decide is breaking the status quo. This question is asked of that sole Black woman living in a white neighborhood who thinks she has made it. At social gatherings with her white liberal peers, the questions wear new clothes. What do you do? How long have you had that car? Are you married? How did you hear about this neighborhood? These, she discovers, are all variations on that ancient and loaded query: Why are you here?

LeXander Bryant with his wheatpaste poster installation

Hanging in the same room is a poster that seems to depict Christ as a Black boy. On his face is the sheen of shea butter, like his mother has generously anointed his whole body. Beneath this image, the moniker “baby jesus” explodes in black-letter font — echoing both the King James Bible and a certain hip-hop Négritude.

For us Black viewers, we must accept our identity with this Black baby Jesus. We must remember our mothers or grandmothers, who became like God when they created luxury in the manger. They protected us from the Herod-like police, offering us trust funds of laughter and full bellies. This inheritance is what Bryant admonishes us to remember; the smoke of onions and meat during a days-long power outage — how our Black parents alchemized jeopardy into jubilee. We know, by the texture of our experience, that in no thesaurus are wealth and love synonyms. Remembering the rich childhoods that our working- and middle-class families stitched together is to resist overarching narratives about Black parenting in this country. We too were baby Jesus; our parents put their hope in us.

LeXander Bryant at Frist Art Museum

“Forget me not” is the groan of the memories. Those communal recollections are the buds that push up through the concrete in Bryant’s centerpiece. They cry out, not to developers, who have bottomless ideas for what to do with other people’s land in Nashville. Not to the scores of newcomers setting up homes in formerly Black neighborhoods. They cry out in blue and white wisps like spirits. To those of us who were there, like they used to say in the Black church, as a cloud of witnesses. Our ears still ring with the good noise of tambourines, still burn from the sizzle of the hot comb. The waves of the river that washed away our fears, yet lap against our waists. Our attempts at freestyling boomerang in the red-brick corners where we left them.

Bryant’s Forget Me Nots is a visual testimony to the South. Each work is a breadcrumb back to the people and the hours. When we are lost, we find a way. Back to Black Nashville. Back past the many thousands gone. Maybe all the way back to 1619, to the hush harbors where enslaved Blacks met in secret to have church. There, we may find our families, eating good dark fruit that will stain our fingers as indelible reminders of home.

Speaking with the Nashville artist about Forget Me Nots, now on display at the Frist