I spent the weekend at various activities put together to honor the 100th anniversary of the Dutchman’s Curve disaster. On Friday night there was a dinner and program at the Bellevue Church of Christ. On Sunday, I went to the commitment ceremony out at Mt. Ararat Cemetery, and then Monday morning, I went to the remembrance at the curve. There were also tours of the Richland greenway and graveside ceremonies at Calvary Cemetery and Mt. Olivet.

Mike Reicher at The Tennessean did a really great job covering the events and the history behind them:

On July 9, 1918, two passenger trains collided head-on at a horseshoe bend in the tracks near present-day Belle Meade, killing at least 68 African-Americans and 33 other passengers and railroad employees. The official death toll remains at 101, though historians consider that an under-count.

I got to watch Reicher work. He was there early, talked to seemingly everyone, and stayed late.

There were a lot of family members at the events — elderly people whose grandparents or grandparents’ siblings had died in the crash. They were there with their families. I spent a lot of time watching the people who were putting on the event or reporting on the event, because it felt intrusive to watch the grief of the families.

I also spent a lot of time thinking about Betsy Thorpe, the author of The Day the Whistles Cried, who spearheaded the weekend’s activities. Thorpe, known as The Other History Betsy in my house, is, like me, a deep lover of Nashville history.

I think, in general, when you study history and write about it, you’re hoping to make sure these people and events aren’t forgotten. And sometimes, you get to meet with family members of the people you’re writing about, and you get to hear firsthand how your writing has affected them, what they knew and didn’t know, what you got right and wrong. And sometimes, though more rarely, your research changes things. You work on something pertaining to history, and it causes something to happen — a marker goes up, a plot of land is saved, the importance of an artifact is remembered.

But it seems very rare that you get to do all three things — honor and preserve the history, allow some kind of public reckoning for the families, and make a change to the city.

With her work on Dutchman’s Curve, Thorpe has done all three. People came out. They heard what Betsy had learned. They saw the historical marker she helped erect. They grieved the fallen and remembered them in public. And the city took it in.

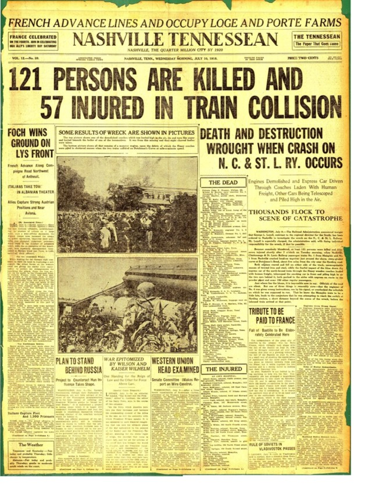

Mayor David Briley spoke briefly on Monday morning. He recalled how he had spent some time reading The Tennessean from July 10, 1918 — the day the details of the crash were recounted in the paper. And he mused on how much the city has changed since then, how even the very language we use to talk about events where so many victims are African-American has changed. Heck, even that we were having one communal event, and not segregated remembrances, shows the massive change.

As we all stood there on the bridge together, the literal white bridge of White Bridge Road, looking down onto the curve where the accident happened, I found myself feeling a deep love for the people of this city, who want to know their history and be changed by it, to honor it and be moved by it.