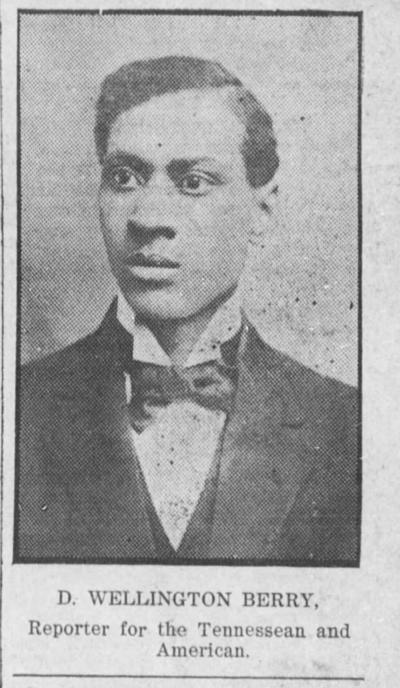

Duke Wellington Berry

OK, you know Robert Churchwell, pioneering Black Nashville journalist? First Black writer for a Southern white newspaper? He wrote for the Nashville Banner starting in the 1950s? That dude?

No? Well, here’s what The Tennessean has to say about him:

Robert Churchwell Sr. was the first black journalist employed at a white-owned metropolitan newspaper in the South.

…

After serving in the Army during World War II, Churchwell earned a bachelor's degree from Fisk University. He joined the Nashville Banner in 1950 but had to work from home. Executives excluded him from meetings and barred him from the newsroom until 1955.

Y’all, this first sentence is not true. I hardly know what to say. It’s what I’ve always been told. It’s probably what you’ve always been told. Hell, I think it’s very likely this is what Churchwell himself was told.

I kind of think the most genuine response I could have to this discovery is to put up a picture of the guy who probably deserves that honor (though, honestly, who even knows?) with me looking gobsmacked and baffled right next to it, and just let that be the column.

Scene readers, this story has it all. A dude named Trout. A poolroom. Mail fraud. Handsomeness. Getting the hell out of Hopkinsville. Reporting for both The Tennessean and the Banner. An illness that required going to Denver to die. And then vanishing from the historical record. Trout is barely in the story, but I feel like you know it’s going to be good when someone with a wild nickname is in it at all.

Sherrod Bryant was a free person of color and probably the richest Black man in Davidson County during his lifetime

Think about it. You hear that George and Bud get into a fight in a pool room in Hopkinsville, that barely registers. Trout and Bud get into a fight? Yeah, someone’s getting shot.

Duke Wellington Berry was born in Hopkinsville, Ky., in 1880 or 1881. He married Mabel Rogers in 1900 when he was working as a coal miner. Like many miners before and after him, he got out of the ground as soon as he could. He opened a pool hall. In May 1906, he was arrested by U.S. Marshals. You’d think this might have something to do with the aforementioned pool hall, likely a den of sin and inequity, gambling and close dancing, but no! He was arrested for mail fraud for advertising a hair product that would “take the kinks out of negro hair.” (That’s according to the Louisville Courier-Journal from May 4, 1906.)

In November 1909, someone named Trout shot someone named Bud and then disappeared. The Hopkinsville Kentuckian reported, “'Trout' is a tough citizen, and spends a great part of his time working on the streets to pay fines for misdemeanors of almost every kind known to the calendar.” The next February, the mayor closed down Duke’s pool room. Immediately after, Duke announced to the paper that he was gong to Nashville.

By 1910, he and his family were living on Jackson Street, and he was, according to the Census, working for the newspaper, though it doesn’t say which one. His byline appeared in the Banner, on an article titled, “Understanding between Races: Declared by Speaker at Colored Conference to Be the Crying Need.” He really hit his stride when he got his column at The Tennessean: “General News of the Colored People.” The news therein included things like, “My cousin is coming to town,” and, “Here’s a bunch of stuff I did.” So that does stretch the meaning of “General” a little bit, but his columns weren’t only about him, and frankly, it did provide a window in to the ordinary, boring things Black people in Nashville got up to, which was quite a contrast to how white papers usually wrote about Black people.

He got sick in 1918, and physicians insisted he go to Denver for the better air. The Tennessean featured updates on how he was doing. In 1922, he died out there.

For nearly a decade, Duke Wellington Berry wrote for the white papers — 40 years before Robert Churchwell. And the very paper that employed him for the longest forgot about him.

This is theft. Berry was stolen from the city. He was erased and forgotten.

Can you imagine how much it might have meant to Churchwell to know that he wasn’t alone? That someone had done this before him, done it well, and thrived?

And think about how the white supremacist narrative is basically that Black people were enslaved, then they did nothing worth talking about for decades, and then the civil rights movement. But Berry’s parents were enslaved at birth. He was in that first generation to be born free, and he was able to start a couple of businesses (albeit shady businesses) in Kentucky and have this grand second act here in Nashville. The children of enslaved people built successful lives and made space for themselves in the broader society.

And then the 1920s hit, and white people lost their goddamn minds. Back came the Ku Klux Klan and anti-Catholic sentiment and the massive pushback to white women’s suffrage, and all kinds of progress was lost. Achievements were forgotten. We had to have a second Black reporter pioneer, because the path didn’t stay cleared after the first one.

It’s hard for me to think too hard on this, considering that we’re all trying to live through this moment of grand recoil here in the 2020s, knowing that Berry was lost due to the grand recoil against post-Emancipation progress. What stories will we lose? What figures will vanish from common knowledge? Will they be found again?

Trump's cuts could kill off the ecosystem of writers, historians, museums and libraries that sustains us

I wasn’t looking for Berry. I didn’t even know he existed. I was just flipping through old copies of the Nashville Globe and I came across the picture you see here. Last week.

And I’m sorry to end on the same note I ended my column on last week, except I still feel the same way. It’s depressing that a man like Duke Wellington Berry existed and left a paper trail and still got erased. It’s depressing that this country is doing that same bullshit today. But here he is, and I feel lucky to get to tell you about him, and I hope you feel lucky to know about him. Maybe we can bring him back into the story where he should be.

The first two decades of the 20th century in the South were full of people like Berry. Who knows if he was the first Black guy to work at a white paper in the South? I don’t even know that I feel confident that he was the first Black guy to do so in Nashville. No one knew to look for folks back that far before. He might be one of many. And maybe we’ll get to find out.