Really, it’s astounding to think about.

Every day, before the first rays of the sun tickle the eastern edges of the county, scores of trucks rumble to a start and fan across the county, dutifully picking up canfuls of refuse. On a rotating schedule all throughout Davidson County, every home and business gets its trash picked up every week. Once a truck is full, it goes to Republic Services’ transfer facility off Lebanon Road near Fesslers Lane, and from there, it heads to a landfill.

Garbage collection is such a part of the routine that we seldom think much about it. It’s like any other utility in that way. Hardly anyone ever thinks about where the water from the tap comes from and how it gets to the faucet, or where it goes once it goes down the drain. The same is true with garbage collection. As long as it gets picked up, most everyone is more than happy to haul their cans out to the roadside once a week.

Nashville makes a lot of trash. Metro Public Works and its contractors collected 228,000 tons of it in fiscal year 2019 — nearly two pounds per person per day. That doesn’t count garbage picked up by private haulers — utilized by many businesses, apartment complexes and condominiums, for example — or construction waste. Add that in, and the overall tonnage pushes up into the millions, according to a 2016 study.

Only one-quarter is recycled or composted — a low number compared even to the paltry 35 percent national average — so that means the rest goes to a landfill.

Burying trash isn’t a new idea. It’s as old as civilization itself, in fact. Without buried trash, archaeologists and anthropologists would have very little information about the everyday lives of those who came before. What’s perhaps most concerning is that in 3,000 centuries of human civilization, no one’s come up with anything better than digging a hole and dumping trash into it, and the existential question of how much the species has really advanced in all that time is a troubling one to consider.

Let’s leave that question to the socialists and philosophers, because there’s a bigger, more immediate problem for Nashvillians: In as little as five years, all that trash may have nowhere to go.

U.S. Route 231 stretches 912 miles between St. John, Ind., and Panama City, Fla. Twenty-six of those miles connect Lebanon and Murfreesboro. It’s a two-lane ribbon of asphalt through rural Wilson and Rutherford counties, almost wholly unincorporated and pockmarked with hardscrabble farm land. Much of Middle Tennessee sits in a basin, and this is, more or less, the nadir of it. The limestone that undergirds us all — in many places, mere centimeters below the dusty soil — creates the unique cedar-glade biome found in this part of Tennessee and hardly anywhere else on earth. In fact, the ubiquity of the cedars (which, a dendrologist would point out, are actually junipers) inspires Lebanon’s name.

Ranching is far more common than crops are on that stretch of U.S. 231, the rocky and paltry soil making it difficult to grow much of anything. But something does grow there, just outside Walterhill in Rutherford County, near the Wilson County line.

It’s a big mound of trash.

Middle Point Landfill is the largest landfill in Tennessee. More than 4,000 tons of trash per day from 34 counties winds its way from homes, down highways, fated ultimately for a long life under the hill known to generations of MTSU students as Mount Trashmore.

Republic Services, which owns Middle Point, says the landfill will be full in eight to nine years. However, the rapid growth of the region — particularly in Metro Nashville and Rutherford County, which combine for 70 percent of the waste that goes into Middle Point — could tighten that window. What’s more, a tornado outbreak or another flood would create a lot of waste quickly, squeezing it further. Given those variables, it could be as little as five years.

Whenever the landfill reaches capacity, the trash will have to go somewhere — but it won’t be Middle Point, and it won’t be in Rutherford County, as the commission there has already decided not to issue a new permit to the existing landfill. Neither will the county approve any permits for a new landfill.

Understandably, landfills are basically the reason the acronym NIMBY exists. Communities aren’t lining up, clamoring to be the site of the next big landfill.

Of course, Middle Point isn’t the only nearby landfill, nor is Republic the only landfill operator. But Metro’s contract with the company runs to 2022 with two five-year extensions, meaning its likely Metro will still be tied to the company when Middle Point hits capacity. The company does operate another landfill in Madison County, outside Jackson, but that’s 100 miles longer than the trip to Middle Point. Technically, the Metro-Republic contract only stipulates Republic accept residential waste at the transfer station, so some Metro trash may already go to Jackson, but the vast majority goes to Middle Point.

Waste Management — Metro’s recycling vendor — operates a landfill outside Camden in Benton County (95 miles west of Nashville) that has plenty of room to grow. But that would require a new round of negotiation with a new company, an eventuality Metro Public Works is at least considering.

“While we will focus more on diverting waste from landfills in the future, we will still need a landfill option for Nashville and Davidson County, and will likely need to put out a competitive solicitation in the future to all waste-disposal companies for future options,” says Sharon Smith, assistant director at Metro Public Works.

C&D Landfill in Bordeaux

Nashvillians are not big recyclers, for whatever reason.

Only about one-sixth of total residential waste is recycled (another 8 percent or so is composted, which solid-waste statistical types combine with recyclables as “diverted” waste), between what is collected once monthly from the Curby bins and taken in at convenience centers. Nationally, the diverted figure is closer to 35 percent.

Recycling isn’t just the green-minded thing to do. As Smith notes, Nashville needs to recycle more because of dwindling landfill capacity. That’s why Metro applied for — and won — grants from the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation and The Recycling Project with the goal of moving from monthly recycling pickup to a biweekly schedule.

But Metro’s budget troubles, combined with factors beyond its control, put the brakes on that plan, which had been set to begin this month.

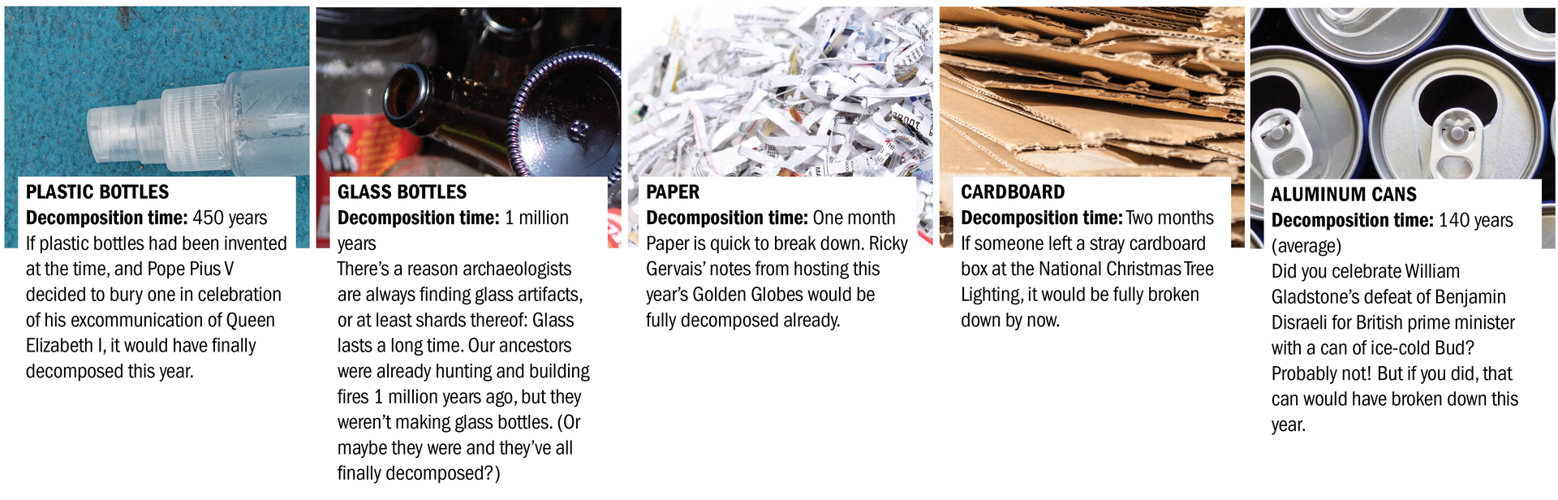

In January 2018, China — which for a quarter-century imported more than half of the world’s recyclables — announced an import ban on 24 different types of recyclable waste, including plastic, as part of its “National Sword” program. The scheme also imposed much stricter standards on handling contaminated waste — which for recyclable goods includes even caked-on food detritus, for example. As a result, plastic imports to China dropped 99.4 percent in less than one year.

During the years of heavy Chinese imports, prices for scrap plastic, paper and metal skyrocketed due to the demand, as the Chinese attempted rapid industrialization of the vast country. As a result, U.S. municipal recycling programs broke even, with some even making a profit. But with China’s about-face, prices are at rock bottom, and Waste Management is reportedly bleeding money.

Until biweekly recycling becomes a reality — the hope is that Metro will be able to fund it in the fiscal year 2021 budget — Public Works is trying to bump recycling in other ways, mainly by making sure people are recycling the right things in the right way. More than 30 percent of what Nashvillians try to recycle isn’t recycled in the end because of contamination.

Yep, that peanut bar jar is recyclable, but only if all the peanut butter is scraped out before it goes in the bin. Cardboard pizza box? Sure, it can be recycled, but there can’t be any cheese stuck to it, or a stray pepperoni, and they can’t be greasy (good luck with that last one, especially). Lots of well-intentioned would-be recyclers collect their bottles and cans in plastic grocery bags. Those aren’t recyclable through your Curby at all (grocery stores will recycle them, however), because they get wound around the sorting equipment. Public Works is putting “Oops!” tags on bins with contamination because education is really the only way to combat the problem.

Metro’s policy is basically this: If you aren’t sure, put it with the trash — but still, seriously, try recycling as much as you can.

While both regular trash pickup and recycling pickup are net losses for the city, on a per-ton basis, recycling is more cost-effective, to the tune of about $25 to $35 per ton.

However, despite Metro’s growth, curbside recycling has actually gone down. And that’s not just per capita, but in real numbers. In fact, tonnage has declined in four of the past five fiscal years, has been on a downward trend since the peak in 2007-08, and is on pace to slide below 11,000 tons for the first time in more than 15 years this fiscal year. Meanwhile, landfill-bound trash is likely to hit a new high-water mark.

recycling at East Convenience Center

So what does the future of Nashville’s trash look like?

China is showing no signs of loosening its restrictions anytime soon, so recycling is likely to be a losing proposition for a little while. Even if China does change its policy, recycling isn’t necessarily a net positive for the environment. Though recycling certainly cuts down on the amount of trash heading to landfills, without a major domestic user, it’s shipped on barges. And barges aren’t exactly the most green solution, particularly if a shipping container goes overboard and dumps its load into the sea. Which happens from time to time.

All that said, Public Works’ master plan aims for “zero waste” in the next 20 to 30 years. “Zero waste” doesn’t mean totally getting out of the landfill game — it’s not that ambitious. It means 90 percent landfill diversion. Though, given the current rate of 25 percent, that’s a moonshot. Recommendations in the master plan are formidable.

First is the creation of an overarching solid-waste authority. Despite consolidated Metro government, solid waste in Nashville is still a patchwork operation, with Public Works itself serving the urban services district, and contractors serving the general services district and the satellite cities. There are different rates for collection tucked into taxes, and ultimately, waste disposal relies on the Metro general fund. Proponents of the master plan say an overarching authority would have the power to bring the entire county under one umbrella, with consistent rate structures and the ability to set countywide regulations.

Ultimately, those regulations would include mandatory recycling and a ban on food scraps in the trash. Food scraps and other compostables like yard waste still make up the largest portion (28 percent) of the landfill-bound trash stream, despite most of it being completely compostable. Metro encourages composting and takes food scraps at its convenience centers. Private businesses now exist to pick up scraps, and Public Works provides compost bins for the asking, but food scraps can still go in the regular trash can with no penalty.

Another point in the long-term plan is “save-as-you-throw,” which seems almost comically simple. The proposed solid-waste authority would provide trash, recycling and compost bins to residents, with the trash bins priced on a sliding scale: the smaller the bin, the less it costs. The idea is that if homeowners have smaller trash bins, they won’t throw away as much.

Save-as-you-throw has been in place in numerous cities, particularly in New England, for years. Worcester, Mass., has been using the plan for decades, and estimates it’s saved the city some $10 million over the past 20 years. Trash volume in Waterville, Maine, decreased by more than half in the first year of SAYT.

Granted, these are small cities, and small cities tend to be more nimble in executing big changes — Worcester, for example, is about a quarter the size of Nashville. Even so, both New York City and Washington, D.C., are considering the program as they strive for zero waste.

That three-pronged, forward-looking approach, according to the Public Works plan, would increase the landfill diversion rate to nearly 60 percent on its own.

But there’s one more step that’s desperately needed, the plan shows, and it seems like a major case of trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube — if the toothpaste was a thousand-year flood of minty freshness, that is.

Nashville’s explosive postdiluvian growth doesn’t amount to simply throwing up towers where nothing used to be, or blocking sidewalks, or causing heretofore unforeseen traffic snarls. It’s putting a lot of trash in landfills, particularly at Waste Management’s Southern Services Construction and Demolition landfill, easily spottable by anyone traveling Briley Parkway west of town.

Metro has virtually no requirements for its construction and demolition waste, other than it can’t be buried or burned on site (boilerplate language in every building permit), so it’s trucked away. The master plan calls for revolutionary changes in the way Metro does business with building contractors.

Many cities already require developers to file a deposit when applying for a building permit, which is remitted once they prove they recycled a certain amount — usually 50 percent — of construction and demolition waste. These programs have dramatically increased landfill diversion, particularly when coupled with a total landfill ban on certain materials. The master plan predicts that implementing a 50 percent threshold in Nashville would increase landfill diversion by another 14 percent.

All told, the top-line recommendations would get Nashville to a diversion rate of 75 percent or so, making that “zero waste” figure not so pie-in-the-sky.

Short of this trash revolution occurring in the short term, Nashville’s best hope is residents and institutions alike committing to reducing waste without the cudgel of government.

Vanderbilt University, for example, announced in January that it is accelerating its zero-waste program to achieve the 90 percent benchmark by 2030, banning single-use plastic bottles (except for laboratory use) and setting up food-waste collection at all dining halls and residential facilities by 2025. Vanderbilt, to its credit, has had an on-campus recycling program since 1990 and is already diverting 47 percent of its solid waste, so it’s playing from ahead.

For now, Nashvillians will have to wait for twice-monthly recycling until the budget firms up, and those who recycle more than the bin will hold are still left dropping their extra off at convenience centers. Composters will have to tend their own bins. Middle Point landfill will still get fuller.

But policy changes, mandates and bans can only go so far. Changing human nature is a tougher undertaking.

Nashville’s future likely involves more recycling, more composting and more tax dollars to fix our garbage problem