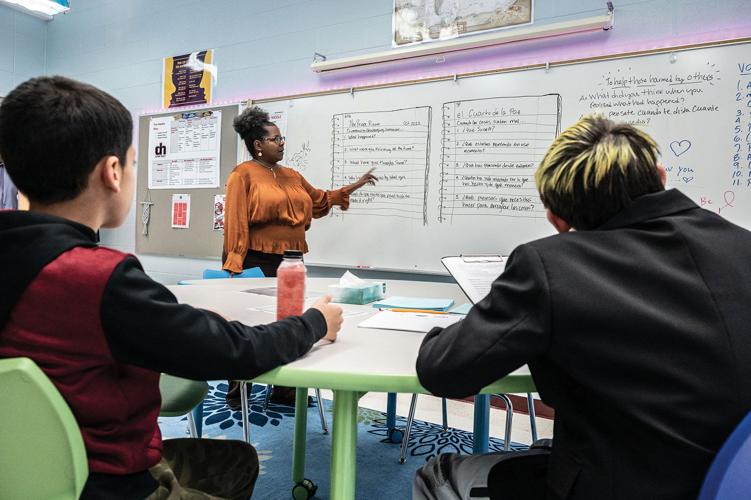

The peace center at DuPont Hadley Middle School feels like a kind of oasis. With its teal accent wall, pink string lights, lots of art and floor lamps that resemble fish tanks, it provides an atmosphere for students and even teachers to cool down and work through issues that arise at school. Posters on the wall raise questions like, “How can we make sure this doesn’t happen again?” and, “What’s needed to make things right?”

This is one of many peace centers throughout the district’s middle and high schools — similar spots in elementary schools are called advocacy centers — designed to administer restorative practice strategies that enhance students’ social and emotional learning while also reducing exclusionary forms of punishment like detention or suspension. Though behavioral approaches and spaces like these existed in Metro Nashville Public Schools before the COVID-19 pandemic, the district has been implementing a district-wide rollout of these spaces to continue addressing students’ mental health.

“Our primary focus is a lot of proactive work, dealing with things on the front end,” says MNPS coordinator of restorative practices Anthony Hall. “In this space … we can help kids to get regulated, help them to work through whatever conflict they might have [and] get them back in class, because the goal is to have them back in class.”

The peace center at DuPont Hadley Middle School

The approach is also intended to enhance academic performance and divert students from receiving more serious consequences for misbehavior, including arrests.

The possibility of student arrests has been on advocates’ and parents’ minds due to an increased police presence this school year, though it’s not a new conversation. School resource officers — MNPD-employed officers who are assigned to middle and high schools — have been around for years. But MNPD Chief John Drake announced in August that, alongside SROs, law enforcement presence surrounding schools would be at the “highest levels ever.”

The approach is a response to the Uvalde, Texas, shooting that left 19 Robb Elementary School students and two teachers dead in May. Chief Drake’s announcement also included the formation of a “safety ambassador” program, which will solicit retired police officers (and others) to return as unarmed, plainclothes security for elementary schools. MNPS Director of Schools Adrienne Battle has not given a specific date as to when we’ll start seeing safety ambassadors in schools, but she tells the Scene that they’re expected to start “as soon as possible.” Alongside the safety ambassador program, MNPD has created a new school safety division — though the department did not fulfill the Scene’s request to interview the new division’s director of training, Scott Byrd.

Increased school security has sparked community debate involving what’s known as the school-to-prison pipeline, or the disproportionate tendency of students of color and kids from disadvantaged backgrounds to end up incarcerated. Once a child comes into contact with the justice system, their chances of future run-ins increase significantly. Even before a student is ever arrested, factors like absenteeism, socioeconomic status, academic performance and disciplinary history create an increased likelihood that they will enter the justice system. And these factors disproportionately affect students of color and those with disabilities. So what is Nashville doing to address it?

The heightened security presence around MNPS stems from the desire — and the responsibility — to protect students and staff while they’re in schools. Though the Uvalde shooting put that desire front and center, it was just one of more than 500 mass shootings that have taken place in the United States this year alone. Just last week, a gunman killed a student and a teacher at a school in St. Louis. Days before the Uvalde massacre, one teenager was killed and another injured during a shooting at Riverdale High School’s graduation ceremony in Murfreesboro. During the 2021-2022 school year, around 16 guns were recovered in MNPS. In the three months of this school year, at least seven guns have been recovered in schools, and several people — including students — have been arrested for threatening violence at schools.

Ask community members the best way to protect kids from internal and external threats, and you’ll receive a wide array of answers. While some would like to arm teachers (a move that Battle does not support), others prefer to rely on trained law enforcement professionals. Still others disagree with having cops in schools altogether.

The Nashville Organized for Action and Hope coalition states on its website that the organization is “campaigning to replace SROs with money for counselors, social workers, and positive discipline methods.” But that’s not something MNPS can fully control. While the SRO and safety ambassador program is a collaboration between the school system and the police department, Battle tells the Scene that “MNPD leads the hiring, the placement, the training and so on for the officers that are in our schools and are patrolling.” The safety ambassador program will rely on education-oriented federal COVID-19 relief money, though it’s not clear how it will be sustained after that funding runs out. The same is true for some of the district’s mental health initiatives.

“What has happened with the school shootings, I think that’s a no-brainer,” says elementary school teacher Wamon Buggs on having police in and around schools. Buggs currently works at Robert Churchwell Museum Magnet Elementary School, though he’s also worked as a court officer for a criminal court judge and as a teacher, coach and assistant principal at multiple schools in and outside the Metro system. He also played for the Green Bay Packers and in the United States Football League in the 1980s.

Elementary school teacher Wamon Buggs

“I would respect what a parent has to say, but at the end of the day, [it] may not be a good idea not to take that seriously,” says Buggs. “[Students] deserve to be given a quality education in a safe environment.”

Critics of SROs argue that they do more harm than good and aren’t always successful in protecting students from outside threats. Take the Uvalde shooting, when SROs and other law enforcement officials demonstrated failure on multiple levels. SROs have also been known to use excessive force on students. Recent body-cam footage from a Chattanooga SRO reveals the officer pulling the hair of a student and pepper-spraying him at school when he wouldn’t take off his backpack.

But SROs are not a monolith. While some mishandle student interactions, others have been successful in supporting them. A video made last year for an SRO who retired from Hillsboro High School includes 20 minutes of former students and colleagues thanking the officer for his service and sharing positive memories of him.

Officer Fredrico Pye, an SRO at Pearl-Cohn Entertainment Magnet High School, says he considers his job a calling.

“We have that rapport and that relationship with these young people, and we know their background, as opposed to sending [a case] out to persons that don’t have that hands-on experience with them, we’ll keep it in house,” says Pye. “A lot of times we deflect from enforcing, because I think that a lot of times [it can] be a very detrimental and traumatic experience for a young person. So yeah, we try to restore in-house.”

When asked by the Scene what he wishes critics understood, Pye responds: “Have an open mindset, be objective. Also, just as we as officers try to be community-oriented officers, I hope those individuals kind of become a part of the community. If they have a concern or an issue with that community, come in and watch and observe and … see the demeanor, see our interactions with our young people. So just [become] knowledgeable as opposed to judgmental.”

But Pye has indeed arrested students. Critics are concerned that police presence in schools leads to increased and disproportionate student arrests. While the Scene was able to obtain juvenile arrest data, neither the Davidson County Juvenile Court, MNPD or MNPS could provide exact numbers on how many arrests have been made at schools — it’s not something that is intentionally, specifically tracked. Additionally, the information that the juvenile court was able to provide came with a disclaimer that it may not exactly reflect MNPD’s data. The Scene was not able to obtain MNPD juvenile arrest data in time for the publication of this story. Even so, the numbers obtained by the Scene clearly indicate one thing — Black youth are being arrested at significantly higher rates than their white peers in Davidson County.

Officer Fredrico Pye

Just as young people of color are arrested at higher rates than their white peers, they are also disciplined at higher rates in schools. Once a student is suspended, the likelihood of coming into contact with the juvenile justice system increases. Should that happen, their likelihood of being arrested in the future also increases.

“There’s a stigma that’s put on them,” says Juvenile Court Clerk Lonnell Matthews. “When they go back in class, their peers are looking at them [like] they’re the bad student. … The other teachers are responding in a way that the child becomes stigmatized and labeled. And eventually, that becomes affirming to the way that that child carries themself and behaves.”

In 2014, the city received funding from the Annenberg Institute at Brown University for a program called Positive and Safe Schools Advancing Greater Equity — or PASSAGE. The goal of the program was to connect city leaders in hopes of identifying and eliminating discipline disparities. Nashville was one of four cities that received this funding, along with Chicago, Los Angeles and New York.

“The only reason we got the grant was [because] we were one of the top school systems in the nation on the disparity in discipline,” says Juvenile Court Judge Sheila Calloway.

Though PASSAGE was able to facilitate citywide conversations on discipline, “the data has kind of faded into the black again,” says Juvenile Court Administrator Jennifer Wade.

“It would be my hope that, whether it’s the [school] board or whether it’s Metro Council, that there’s a push to reactivate it and get it back to intentionally following data and making sure that people [are] reporting what they need to report,” says Calloway.

With an increased police presence at MNPS and the lingering trauma of the ongoing pandemic, one could argue that the need to review data and set specific goals around disciplinary equity is greater than ever. Students have not been immune to the tragedies of the pandemic — some lost family members, while others had to stay home in potentially dangerous situations or take care of siblings while their parents worked. That trauma — compounded by the nationwide conversation about racial injustice, increased attention on police killings and constant news of mass shootings — is something that students carry into schools with them.

A 2019 investigation by The Tennessean found that, even with the work of PASSAGE, MNPS’ disciplinary disparities remained. While school district discipline data is more accessible than juvenile arrest data — you can access it instantly via MNPS’ open data portal — it’s not entirely reliable either. The Open Data Portal Behavior Data Guide states: “The district is not liable for any deficiencies in the completeness, accuracy, content, or fitness for any particular purpose or use of any public data set, or application utilizing such data set, provided by any third party. Data may be updated, corrected and/or refreshed at any time.”

The latest behavioral data set from January 2022 indicates that, throughout the district, the highest rates of suspension are attributed to students with disabilities, African American students and economically disadvantaged students.

It’s not a coincidence that disparities in discipline data are similar to those of youth arrest data. There are many factors in a child’s life that can quickly compound and lead to suspensions and possible arrests, and they’re present long before the child enters a school building.

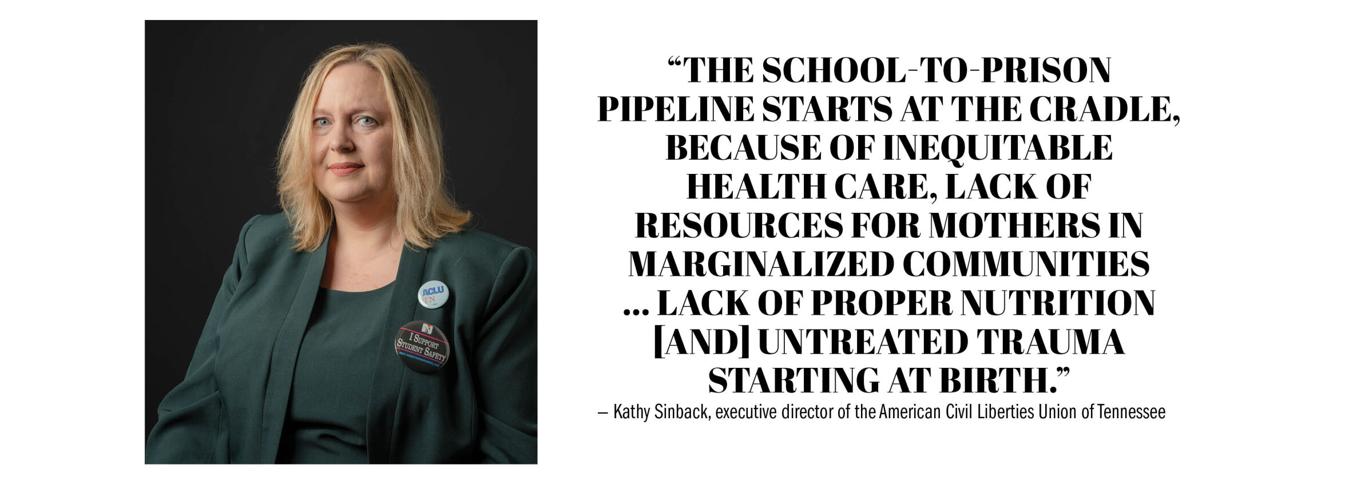

“The school-to-prison pipeline starts at the cradle, because of inequitable health care, lack of resources for mothers in marginalized communities … lack of proper nutrition [and] untreated trauma starting at birth,” says Kathy Sinback, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Tennessee. “So even prior to being school age, we see kids who are not getting the resources that they need. And the neurological development between 0 to 3 is really the most critical time in a child’s life. And then what we see is those inequities that are happening between the cradle and preschool continue on and actually get exacerbated once the child enters the educational system. Then they are already at a disadvantage when they walk in, and then that disadvantage is not effectively addressed in the school system.”

Sinback has decades of experience in this realm. She’s worked as a juvenile public defender, a juvenile court administrator and an attorney for both MNPD and MNPS. “We know what we need to do,” says Sinback. “I think everyone who’s working in this space of the school-to-prison pipeline — whether it’s educational administrators, police, courts, mental health providers, community organizations — we all know what kids need, but we continue to not provide them with what they need. And I think that’s where the disconnect is.”

Addressing inequities that contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline is work that extends beyond education. It means equitable access to health care, housing, nutrition, mental health support, enrichment opportunities and more. Those needs apply not just to students, but also their families. Wamon Buggs connects it all back to funding.

“You don’t put [in] the resources, you’re going to have the issues of people not being able to really do anything to take care of themselves and be successful,” he says. “It costs a lot of money to live in Nashville. It may be, what, 80-plus-thousand dollars for an individual to survive and thrive living in Davidson County? When you look at the population of kids that we serve in the 37208 ZIP code and look at their incomes and you do the math, it’s almost impossible to do what you need to do to experience what life has to offer, or what Nashville has to offer, for that matter.”

According to unitedstateszipcodes.org, the median household income in 37208 is $22,409. Research from the Brookings Institute states that this ZIP code, which is in a predominantly Black area in North Nashville, as of 2018 had the highest incarceration rate in the country for those born between 1980 and 1986. It also listed the childhood poverty rate at 42 percent, and the college attendance rate at 30 percent.

Pearl-Cohn High School is located in the 37208 ZIP code. Ninety-one percent of its students are Black, and 14.2 percent of its African American students have been suspended, according to MNPS data from January 2022.

Statistics such as these are the result of multigenerational socioeconomic factors and long-standing racist practices like redlining and the construction of I-40, which tore through North Nashville a half-century ago with devastating economic consequences — consequences planners wanted to forego in whiter parts of the city. Throw in Nashville’s rising cost of living and the gentrification that is displacing many families, and you can begin to understand how students could act out in school and face subsequent punishment. While these factors are prevalent in North Nashville, they are not isolated there.

Leaders at both MNPS and the juvenile court are aware of this, and working to prevent compounding disciplinary implications by employing community supports, social and emotional development, youth-led courts that handle disciplinary matters, and other restorative justice practices. Just as peace centers exist to prevent exclusionary consequences in schools, Wade tells the Scene that the juvenile court tries to divert low-risk cases to other community partners that can provide mental health support or family conflict resolution.

Says Calloway, “When you look at recidivism rates — the rate that youth come back into the system after they’ve been arrested or they’ve been brought into the system — those youth that we divert from the system, the recidivism rate [is] around 6 percent, versus those youth that we keep in the system, that we keep on some type of supervised probation or send to the Department of Children’s Services … those recidivism rates are at least 20 percent and above.”

The Davidson County Juvenile Detention Center tends to hold youths who are deemed a high to medium risk to the community. After their trial, they may be routed to the Department of Children’s Services, which is currently understaffed and overwhelmed. Some youth sleep in offices because there aren’t places for them to be housed.

Juvenile Court Judge Sheila Calloway

“Decades of poor policies by politicians have led to this crisis,” reads a statement from a DCS worker via a recent press release. “Bill Lee has only made it worse. All of the problems with the department fall on the shoulders of frontline staff. You’re not going to see anyone from ‘leadership’ helping to sit with these kids. There are no beds, no showers, no nothing for these kids except what staff purchase for them out of our own pockets.”

Gov. Lee has been vocal about culture-war scenarios like the Pediatric Transgender Clinic at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital following unfounded claims of child mutilation by right-wing activist Matt Walsh — but he hasn’t been vocal when it comes to the DCS situation. When asked for a statement from the governor, a spokesperson redirected the Scene to a statement from DCS Commissioner Margie Quin: “Like many employers across the country, DCS has been impacted by workforce shortages. We have addressed the issue through consistent pay raises for case workers and will continue to deliver the resources DCS needs to protect children.”

Lee’s response to school safety has been lukewarm. Following the Uvalde shooting, he signed a school safety executive order featuring guidelines on security and support from the state. Last week he released a “Safety Toolkit” designed to get families engaged with school safety. Lee has not, however, addressed gun access — in 2021, his administration loosened gun laws despite opposition from law enforcement agencies.

“We’re kind of accustomed to doing what’s necessary for Metro Nashville Public Schools,” says Battle. “We don’t wait for an executive order. … We have a larger city issue, state issue, national issue with regards to the safety in our communities, and the [gun] access that our young people have.”

Preventing young people from entering the school-to-prison pipeline requires a holistic community approach. This starts with recognizing students’ trauma and emotions rather than seeing young people merely as data points. Calloway notes that she’s “very careful about calling them children. They’re all our children — I think ‘juvenile’ gives it a very negative connotation.”

It also means making sure young people have access to food, safe schools and support from caring adults who are willing to address the root causes that lead to misbehavior and disciplinary actions. However, these ideas can’t be fully addressed without proper support — a matter that MNPS, DCS and other entities are struggling with.

“[Restorative justice] really doesn’t help,” says one teacher who wishes to remain anonymous due to fear of retaliation. “It’s good in theory, but in practicality, it’s really not.” This teacher agrees, however, that the approach would be more effective if schools were fully staffed with enough counselors.

While research by groups like the Justice Research and Statistics Association supports the effectiveness of restorative justice practices, the approach needs resources and community buy-in before it can be fully realized. Addressing students’ mental health is also a form of addressing school safety. In the absence of full, proper funding and staffing for MNPS and other organizations in Nashville, community members can step up to support the city’s children. This can include volunteering with or donating to organizations that work with youth, tutoring or mentoring students, and advocating for change from city leaders.

“We have had the conversation about the school-to-prison pipeline for a very long time, even when I was a young person in school,” says Matthews. “Acknowledging and being aware that the pipeline exists is one thing. Working on ways to dismantle it is another task that is really going to take the will of everyone. It’s going to take a push from community, but it’s also going to take leaders to be able to just have the wherewithal to say, ‘Hey, we want to fix this. And we want to get it right.’ ”

Update: This article initially noted that arrests of Hispanic minors increased from 11 percent in 2012 to 18.75 percent in 2021. The correct numbers are 12.6 and 20.9 percent, respectively. We regret the error.