Lee Weidhaas

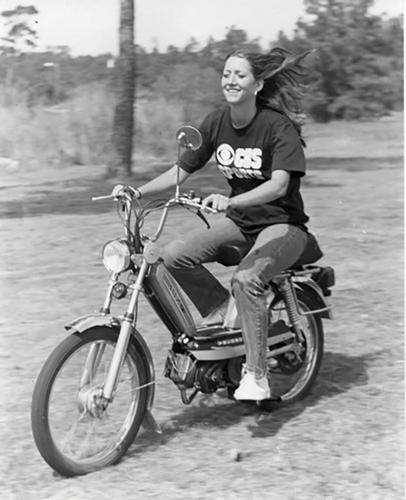

Lee Weidhaas

Art director, artist, manager of madness

Lee Tyler Weidhaas arrived at the first offices of the Nashville Scene, in Maryland Farms of all places, and asked for the editor — and at the time, that was me. In her hands were a stack of newspapers: copies of Richmond Style, a beautiful tabloid weekly. Weidhaas had been its art director, and had made it beautiful.

“I see you’ve put out a couple of issues,” she told me. “Take a look at what I’ve done at Style. You guys could use some help, I think.”

She was low-balling it by a country mile.

Over the next decade, Weidhaas set her imprint on the Scene in ways known and unknown, but in ways that focused her graphical high-beam on how the weekly paper looked. She was a magician of the typographic arts, knowing how a brittle serif headline spoke in utterly different tones than a bold Helvetica. She was a bracingly clean designer; give her a double-truck spread as the opener for a cover story, and she’d pull a reader right into her zone.

But it wasn’t just the artistry. Weidhaas, from day one, was the manager of the madness. As Tuesdays — deadline days — wore to their ragged and exhausted end, she was the glue that bound up the paper in one glorious, imperfect mass, and managed the send-off to the printer. She did not make friends with staff, but she earned their respect.

On top of it all, Weidhaas had an editorial awareness that to this day goes unrecognized. She came up with the idea for the Scene’s annual “You Are So Nashville If …” contest, which has now run for 34 years straight. She came up with “Nashvillian of the Year.” She came up with countless other story ideas and packages that remain to this day.

It was shocking to learn that Weidhaas had died so young, because she was so strong in the early days, so capable of pushing our heaving paper out the door every week. All I can say to Lee now is thanks for what you gave us. —Bruce Dobie

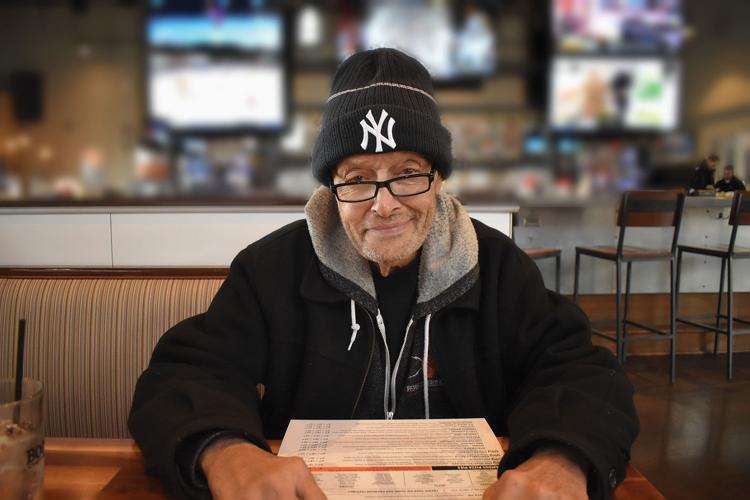

Mark Howard

Sports anchor, broadcast journalist

Mark Howard joined NewsChannel 5 in 1986 and spent 20 years as the station’s weekend sports anchor. After leaving NewsChannel 5, Howard joined 104.5-FM The Zone as a co-host of the popular morning-drive sports talk show The Wake Up Zone along with former Tennessee Titans tight end Frank Wycheck and Vanderbilt director of digital operations and broadcaster Kevin Ingram. The show quickly became the No. 1-rated sports talk show in the city, and Howard was a Zone employee for 21 years.

Howard also had stints hosting the Nashville Predators pregame and post-game shows on then-Fox Sports South, the Titans post-game show, and as an occasional fill-in host for 102.5-FM The Game this year. Howard was referred to by many as a walking sports encyclopedia, and there wasn’t a sport or local team he didn’t know or wouldn’t talk about. Howard will be fondly remembered for his wisdom and ability to connect and interact with fans.

“Mark was a respected colleague, a kind heart and a good friend,” Nashville Predators play-by-play broadcaster and former colleague Willy Daunic says. “He was always prepared and extremely knowledgeable. Most important … nobody was more encouraging to his peers.”

Howard was 65. —Michael Gallagher

Beth Foley

Artist, master of the macabre

Beth Foley was a master at painting the dark and macabre, but always with a lightness that transcended her subject matter, which included everything from the Holocaust to grim fairy tales.

The Philadelphia native moved to Nashville in 1998, and she lived here until her death in March at age 71. She exhibited locally at David Lusk Gallery, in addition to galleries and museums across the country. Her final show, 2020’s Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory, was hosted at Gallery Victor Armendariz in Chicago. The exhibition used Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” as its inspiration — Foley updated the iconic American couple with new iterations, such as “Muslim American Gothic,” “Gay American Gothic” and “Hillbilly American Gothic,” to better reflect the diversity of American life.

She is survived by her husband Robert Doerschuk, and her children Jessica Foley and Ivan Doerschuk. —Laura Hutson Hunter

Margaret Keane

Artist, inspiration

Margaret Keane, the artist who became famous for her paintings of big-eyed children, was born Margaret Doris Hawkins in Nashville in 1927.

The doe-eyed waifs in her paintings were admired by everyone from Andy Warhol to Tim Burton, whose 2014 film Big Eyes cast Amy Adams as Keane. Keane’s formal training began when she was 10 years old, when she took art classes at the Watkins Institute — now known as the Watkins College of Art at Belmont University. At the height of her popularity, her paintings were ubiquitous — like the fine-art version of a Peanuts cartoon. However, her success as an artist came at a price — her second husband, Walter Keane, passed off the paintings as his own. Margaret received authorship of her works after a long legal battle that culminated in a kind of courtroom painting competition in 1986 — Margaret completed a painting in less than an hour, while Walter complained that his arm was too sore to lift a brush.

She resided in Hawaii for 25 years, then moved to California and settled in Napa Valley, where she lived with her daughter, Jane Swigert. —Laura Hutson Hunter

Gardner Orr Smith

Volunteer, socialite, Betty Banner

You are so Old Nashville if you were born here and went to Parmer School, Ward Belmont, Harpeth Hall, then Randolph Macon College for Women. Gardner Orr Smith’s path through life follows a prescribed timeline for women of her status in that era. She was a June bride to her high school sweetheart, joined the Junior League, had three children, volunteered for their schools, worked on the Swan Ball, played bridge and mahjong, and had a cottage in Beersheba Springs. She was a member of the blue-blooded, fastidiously guarded Centennia l Club, and treasured her inclusion in The Study Club, which it is noted was founded in 1914. (The closest thing a web search finds more than a century later is The Study, an upscale cocktail bar in The Register, a private social club with “onsite experience specialists.” So very New Nashville.)

Smith, as her obituary revealed, also belonged to a small, select and not-very-secret club of women who for decades covered society for the Nashville Banner, writing under the pseudonym Betty Banner. She wasn’t the first Betty, or the last Betty, but Gardner Orr Smith was the quintessential Betty. —Kay West

Joe Biddle

Sports reporter, veteran

When Gannett bought and closed the Nashville Banner in 1998, there were many things that lived on beyond the scrappy afternoon daily’s last edition, but none more visible than the bumper stickers.

“I BEAT BIDDLE” was what readers who outpicked sports editor Joe Biddle in a weekly pick ’em contest would win. For years, the stickers were found on cars throughout Middle Tennessee, proud displays of pigskin prognostication for the owners and a genius bit of guerrilla marketing for the Banner to promote both the paper and its star columnist.

Born in East Tennessee, Biddle was a high school classmate and friend of Steve Spurrier. He came to the Banner in 1979 after a decade in Daytona Beach writing sports and a tour in Vietnam. Biddle was a gifted features writer, and his true calling was revealed when he was promoted to sports editor in 1981 and he assumed a thrice-weekly sports column anchored down the left side of the sports page. He could be glib or serious, but Biddle found a huge following with well-reported opinion pieces that forced sports readers to think. One of the first print columnists in Nashville to embrace sports-talk radio, he had a partnership with George Plaster that was, for a time, appointment listening.

Biddle loved a scoop and he loved a good laugh, as evidenced by the time someone took a knife to the famed bumper stickers and removed the “AT” from the second word. Joe proudly displayed the new one on his bumper: “I BE BIDDLE.” —Steve Cavendish

Ralph Emery

Country music broadcast legend

On Jan. 15, beloved country music personality Ralph Emery died at age 88 following a short illness. A New York Times obituary referred to Emery by his long-lived nickname, “the Dick Clark of Country Music.” It was a fitting moniker, as Emery employed his many talents across radio, television and live events for more than six decades.

Emery launched his broadcasting career at Paris, Tenn.’s WTPR and took on radio jobs at a variety of other stations, including Nashville’s WSIX; this brought him on-camera work for the ABC affiliate’s television arm, something that grew to be a staple of his career. His lengthy tenure as an overnight DJ on WSM brought him greater fame. He was beloved by fans and musicians alike, including early interview subjects like Loretta Lynn and Willie Nelson — his minor kerfuffle with The Byrds notwithstanding. Emery appeared as an announcer on Opry Almanac, which was broadcast on WSMV and eventually evolved into his best-loved TV work: The Ralph Emery Show, a morning variety program that aired from 1972 to 1991 and became a showcase for up-and-coming talent.

Emery continued his broadcast career right into the 2010s, with programs like TNN’s Nashville Now in the 1980s and early ’90s and the weekly show Ralph Emery Live on the RFD network in the Aughts and 2010s. A member of the Country Music Hall of Fame and the National Radio Hall of Fame, Emery left behind his wife of 54 years, Joy Kott Emery, as well as three sons and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. —Brittney McKenna

John Conlon in 2020

John Conlon

Visionary with the booming baritone

John Conlon, who is probably best known for his role in the rise of independent radio station Lightning 100 in the early to mid-1990s, died on March 28 after a lengthy struggle with a number of health issues.

A native of New York City, Conlon was a Vietnam veteran who took a job with a political consulting firm after leaving the Army. That led to four years in Washington working with the Jimmy Carter administration, where he began to develop the marketing expertise that he brought into play at WRLT. Conlon joined the station shortly after it moved to Second Avenue in the early ’90s.

As creative director of WRLT, Conlon played a key role in the revitalization of the downtown area. He embraced the concept of “The District” and promoted it on air. He also was instrumental in the successful launch of Dancin’ in the District, serving as entertainment producer for the long-running free weekly live music series.

“Much to our surprise, at one point we were doing as many as 15,000 people on the river downtown, where nobody ever came,” he recalled in a 2019 interview with WXNA radio host Peter Rodman. —Daryl Sanders

Bill Verdier

Bill Verdier

Community radio champion, flame-keeper for Irish music in Nashville

Growing up in New England, Bill Verdier developed a love for music early on, beginning his studies on the violin as a preteen and continuing through the university level. Experiences like watching eminent Irish fiddler Kevin Burke perform and hosting a show on Bridgeport, Conn.’s community radio station WPKN — which boasted a vast collection of music from different folk traditions — sparked a lifelong passion in Verdier for Celtic music in general and Irish music in particular. In 1994, he moved to Nashville, where he recorded and performed with a variety of Irish and Celtic groups like The Rogues and Isla, and hosted jam sessions that have cultivated the tradition in our area for future generations.

When a crew of enthusiastic volunteers set about organizing community radio station WXNA ahead of its launch in 2016, Verdier was right at the vanguard. Down the Back Lane, a two-hour celebration of Celtic music and a hub for news on the local scene, has aired from 4 to 6 p.m. on Sundays since the station went on the air. While he was home in Bridgeport for a visit with family, Verdier died on Feb. 25. He was 64 years old. Among those who survive him are his partner Anne Hoos, many family members, friends and bandmates, and his Down the Back Lane co-host Kevin Donovan, who continues the show. —Stephen Trageser

Eliud Treviño

Pioneer, pillar, patron

Born in Texas to Mexican parents on Jan. 10, 1945 — the same day as Rod Stewart — Eliud Treviño was his own kind of local rock star.

A pioneer of Spanish-language media in Tennessee, Eliud began by renting a gospel station, WNQM-AM 1300, for a few hours at night. That was the launch of Radio Melodias and of his vast legacy that positively touched the lives of thousands of people in the local Latine community, including mine. For almost five years starting in 1997, I would drive up Ashland City Highway every Tuesday night to get to WNQM. Eliud would open the door while offering his signature big smile, beaming upbeat vibes thanks to the music he loved and shared through the airwaves. I was there to co-host the talk show El Café de Las Siete, a volunteer project he enthusiastically supported in order to bring essential information to his growing audience of recent immigrants trying to make Nashville home. That resolve to serve our community led him later to found a newspaper, El Crucero de Tennessee, and an online streaming show.

Always wearing a suit and tie, Eliud used his microphone and pen as forces for good for almost 30 years. He became a pillar of Nashville’s Latine community. However, it was the individual acts of kindness that he offered — like his friendly smile — to every person he met that made him a true patron of our comunidad. In January of last year, news spread that COVID-19 had taken the life of our beloved friend Eliud, and an avalanche of social media posts told the story of a genuinely kind man with a generous heart who opened doors, mentored, gave financial support, kept in touch, cared, and shared his warm humanity.

As he was for so many people, Eliud was a witness and a friend during a very important stage in my life, my first years in Nashville and my first professional steps. The story of how Conexión Américas was born is not only mine, but in the little bit of my story, of the route that made me take that path, there is undoubtedly that weekly drive to WNQM and Eliud’s long-lasting legacy. —Renata Soto

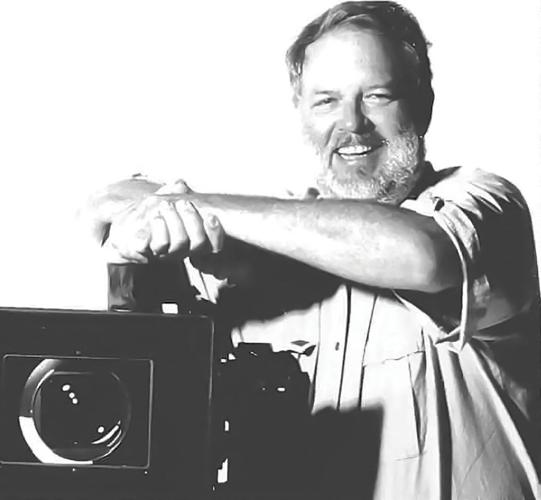

John Cherry

John Cherry

Filmmaker, local innovator

John Cherry, a longtime resident of Williamson County, helped create the lovable good ol’ boy Ernest P. Worrell character alongside then-rising stand-up comic Jim Varney, who starred in the role that would wind up defining both of their careers. The character was created for his ad agency Carden and Cherry to help advertise a then-rundown Beech Bend Raceway Park in Bowling Green, Ky.

In a 1990 interview with Entertainment Weekly, Cherry described the appeal that Ernest had during the advertising days. “Every time we do a study on who Ernest appeals to, it’s the under-13 and over-35 age groups,” Cherry said at the time. “If you’re under 13, it’s OK, and when you’re over 35, you know it doesn’t count anymore — you don’t have to be cool.”

The Ernest character first was used in regional advertisements (including an eight-year run with Nashville’s Purity Dairies) and in short comedy skits before he hosted a direct-to-video special, Knowhutimean? Hey Vern, It’s My Family Album, in 1983. He made his theatrical debut in 1985’s subversive cult film Dr. Otto and the Riddle of the Gloom Beam, which saw Varney play seven roles, including Ernest, the titular Dr. Otto and his recurring character Auntie Nelda. That film started Cherry’s longtime practice of mainly shooting the Ernest films in and around Nashville.

After long contending with Parkinson’s disease, the filmmaker died in May at age 73. Cherry is survived by his children Josh, Emilie and Chapman. —Cory Woodroof