WXNA BOARD MEMBERS FROM LEFT: Jonathan Grigsby, Laura Powers, Randy Fox, Ashley Crownover, Pete Wilson, Roger Blanton, Heather Lose

IN THE WXNA STUDIO: Roger Blanton

"You can't put your arms around a memory

You can't put your arms around a memory

Don't try

Don't try"

And with that, on June 7, 2011, Johnny Thunders' band ground to a halt, the house engineer flipped a switch, and 91.1 FM, the frequency that had carried the terrestrial broadcast signal of Vanderbilt University student radio station WRVU for the previous six decades, fell silent.

In addition to student DJs, WRVU in its broadcast days was also home to a mind-boggling variety of shows hosted by non-student volunteers. Community radio is by no means unique to Nashville, but the oddball mix of sounds you could hear on the station — from punk, honky-tonk and bluegrass to indie rock, industrial dance and experimental music, all exquisitely curated by people with a deep knowledge of music and an abiding passion for sharing it — was a thread that stood out in the fabric of the community. No matter what your version of Music City looked and felt like, fandom of 91 Rock was a badge you could wear with pride. Even as the media landscape fragmented into a collection of ever-more-specific commercial niches, the station brought together some 30,000 listeners each week.

But WRVU's role in the community was a happy accident. Nowhere was it written that the station had any purpose beyond giving students practical experience with a broadcast medium that began to look increasingly old-fashioned. Changes at the station, beginning with a controversial 2009 cap on community volunteers, led a group of DJs and supporters to organize as a federally recognized 501(c)(3) nonprofit called WRVU Friends and Family. Much to their dismay, VSC Media, a separate company set up by the university to operate its student publications and WRVU, announced it was considering selling the station's broadcast license, relegating WRVU to a half-life of streaming online and to a significantly smaller audience on HD radio.

Under the easier-to-chant nom de guerre "Save WRVU," WRVUFAF attended meetings with VSC representatives and hosted a slew of events to raise awareness and voice their opposition. VSC remained unmoved, and in an agreement that it tried aggressively to keep private, it sold the license for $3.35 million to local NPR affiliate WPLN, which now uses the 91.1 FM frequency to broadcast WFCL, a 24-hour classical station.

The deal took effect on June 7, 2011, the afternoon that veteran community DJ Pete Wilson cued up Johnny Thunders, just as he was being ushered out of the studio during what he was told was a maintenance break. Through 2012, WRVU Friends and Family continued their fight, petitioning the Federal Communications Commission to block the sale of the license. But even had those efforts been successful, calling relations between Vanderbilt and those involved with Save WRVU strained would be a monumental understatement. The chances that the station could regain its former place in the hearts of locals were slim.

Over the next two years, the tide of "It" rolled in, bringing attention from the international press and the production of ABC's big-budget drama Nashville — as well as skyrocketing property values and a kind of identity crisis. The city has struggled to retain our cherished small-town feel while growing exponentially larger. One thing that no one was talking about, however, was local radio.

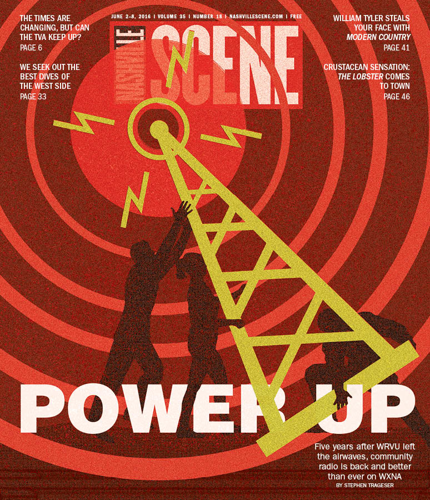

On Dec. 4, 2014, that changed. WRVU Friends and Family announced they had received a construction permit from the FCC for a low-power community radio station. The free-form, hundred-stations-in-one model of WRVU in its glory days was about to be reborn on 101.5 FM as WXNA. With community radio as the main focus rather than a beneficial byproduct, it would be better than ever — provided they could build a station from the ground up in 18 months.

Following a crash course in setting up a radio enterprise and an intense period of fundraising — during which ecstatic supporters raised more than $55,000 in 45 days — WXNA is tantalizingly close to its official sign-on. After a nail-biting six weeks of waiting for an Internet provider to install the hook-up at their broadcast tower and a week of on-air testing, the seven members of the board will convene at the studio at 10 a.m. Saturday, June 4, to kick off a two-day opening ceremony. On Monday, June 6, they'll fire up a debut schedule featuring more than 80 volunteer DJs who will contribute 16 to 17 hours of original programming each day, seven days a week.

"In the beginning," says Heather Lose, longtime host of The Honky-Tonk Jukebox on WRVU and now president of WXNA, "it was a bunch of old punk rockers sitting around in our Chuck Taylors going 'Well, OK, let's throw this up against the wall and see if it sticks.' "

Save WRVU may not have accomplished its intended mission, but it did its part to ensure the spirit of the station would live on. It kept former DJs banded together, and it also kept Lose in contact with Sharon Scott, president of WRVU Friends and Family.

Even before the petition to block the sale of WRVU's license failed, Scott was investigating new developments related to low-power FM community radio stations, which had effectively been kept confined to the outermost parts of metropolitan areas. Radio Free Nashville — which went live in 2005 from its tower out off Highway 100 — strained to reach further east than the Belle Meade Kroger for most of its first decade on the air, until the FCC approved an FM translator that duplicates its signal on a tower closer to the city.

The Local Community Radio Act of 2010 eased restrictions that previously hamstrung low-power FM, opening up opportunities for community stations to take root in urban areas. Scott, who moved to Louisville, Ky., to help start arts-focused LPFM station WXOX, met with Lose and her fellow former WRVU DJ (and Scene contributor) Randy Fox in March 2012 to tip them off that the FCC would soon open another window to file for an LPFM license.

Lose has a long history with local radio, from growing up with a boom box tuned to WKDF and WRVU to working at Lightning 100 and Thunder 94. Five years at WDBX in Carbondale, Ill., a community station on the campus of Southern Illinois University with one full-time employee, convinced her that the Save WRVU crew was up to the job of running a station that would be more than just a vehicle for them to get back on the air. For Lose, it would help give Nashville the thing it needs most in this time of rapid change: a sense of community.

"This may sound all highfalutin, but music changes people," Lose says, with a confident and conspiratorial grin. "It's a cultural art form. It helps you find your tribe. Sometimes it helps you find yourself. When you can't find your own words to express how you feel about something, you can let someone else do it for you.

"Radio is not just about the music — it's about the personality of the person who is curating this experience," Lose continues. "You can do so much with a pause, with the tone of your voice, how you set up a song, how you make these connections between songs. And it's through the enthusiasm of the person who's playing this stuff for you that you can find your way into something that you might have turned your back on."

And then there's the zing of pleasure the DJ gets from making those connections.

"When I was at WRVU, I got to turn some people on to Merle Haggard — in Nashville!" Lose recalls. "I would get calls saying, 'Who is that?' 'That is Merle Haggard. You oughta know who Merle Haggard is.' Because WRVU was on the air, someone got to hear 'Swingin' Doors,' and got to call in and go, 'This is so clever and awesome. Who is this?' Well, this is a name you've heard a million times. Maybe you think you don't like country. Maybe you think you don't understand the line between Merle Haggard and X or Social Distortion. But stations like this can help draw those lines. That's what I get off on. That's what I want."

Over roundtable meetings at the Gerst Haus, Lose, Fox and fellow WRVU veterans Ashley Crownover, Pete Wilson and Roger Blanton laid out plans for the new station and began the Tetris-like process of filing the necessary documents with the FCC. Besides naming themselves as the board of directors, writing a mission statement and making up a sample schedule, they had to propose a location for their studio within 10 miles of each of their home addresses, plus a site for the transmitter no further than 10 miles from the studio — all while speculating on a nonexistent budget.

They knew that if their application was granted, they would have to rally support from the community with lightning speed. From Lose's and Fox's work in advertising, they knew having an emblem that immediately communicated what they stood for would go a long way, so "WXNA" was the natural choice among the available combinations of call letters. The "NA" refers to Nashville, and the "X" taps a vein of nostalgia for the idealism of the '50s and '60s with a nod to Mexican radio station XERF, the 250,000-watt "border blaster" that broadcast the howls and growls of Wolfman Jack across most of the continental U.S.

LPFM stations don't have the luxury of transmitting with XERF's paint-peeling power. They're limited to 100 watts, miniscule compared to most commercial stations and a staggering one-hundredth of WRVU's former 10,000-watt signal, but such stations can reach surprising distances when unobstructed. As an alternative to the curated playlists that saturate our listening culture, they have a unique power to bring people together. The tattoo of a firecracker on Heather Lose's wrist — something small but loud, which draws a crowd, and even has a little local flavor if you count the fireworks stands that dot Tennessee's interstates — inspired Roger Blanton, who makes his living in graphic design, to create the station's crossed-fireworks logo.

After a marathon session of assembling their application in Lose's home office, the group filed with the FCC on Nov. 11, 2013. Their timing was perfect. It was right at the end of the most recent LPFM filing window the FCC has offered in Tennessee. According to REC Networks' Michelle Bradley, a radio analyst and LPFM advocate who lobbied loudly in Washington for the Local Community Radio Act (and who has helped WXNA and dozens of other stations navigate the FCC application process), the FCC may not open windows to consider additional LPFM applications until at least 2019.

But after WXNA's filing came a long wait. The FCC posts notices of new permits on its website as they are granted, but communication with the applicants moves at the speed of federal bureaucracy. On Dec. 4, 2014, Fox began to get phone calls from unfamiliar numbers that turned out to be radio equipment dealers. A routine check of the FCC postings by Lose was the confirmation: WXNA had been granted a construction permit.

Lose describes the board's mood as it shifted from giddy jubilation to a sobering realization of the task ahead.

"Holy shit! We've got 18 months to build a fucking radio station from scratch."

Following the road from receiving the permit to going on air was going to take substantial amounts of both community engagement and an understanding of finance. Multiple simultaneous tasks remained on the table, from raising the money to pay for the equipment they'd need to locking in the studio and transmitter site to training the volunteer DJs and arranging the programming schedule.

To share the load, the board enlisted two new members, also former WRVU DJs whose careers made them a perfect fit for the nascent station: Laura Powers is an award-winning ad copywriter, and Jonathan Grigsby is in charge of IT at an accounting firm.

Though the response to WXNA's permit announcement was enthusiastic, it required plenty of effort to turn that into financial backing. First, the board took turns staffing DJ booths at events around town, spinning records to elicit donations and selling swag emblazoned with the logo Blanton designed. That helped build up a fund for paying the bills once the studio was up and running, but WXNA still lacked a studio. For that, crowdfunding appeared an attractive option.

"I don't think any of us knew how much work we were in for with the Kickstarter campaign," says Powers. "I was kind of naive, like, 'Well, we'll just put it up, and people click on the thing and give you money.' It's not exactly that easy. We had to go out and beat the bushes and work to get the word out about that. We've been living and breathing this for so long, and we feel like we've been talking to everyone about it, so it's hard for us to imagine that there are people out there who don't know."

The six-week campaign exceeded its goal by 10 percent, pulling in $55,310 from individuals as well as local businesses that claimed sponsorships as their premium. Per the FCC's rules for noncommercial radio, WXNA can mention that an entity is sponsor, as long as the station doesn't endorse the entity's product or service. A few individuals have also reached out directly with contributions, but Grigsby says the majority of the costs to start the station and run it for six months came from the Kickstarter campaign. After that, it'll be time for on-air pledge drives — but luckily there are plenty of DJs to call on.

And there was still a studio to consider. Conveniently, artist management group Thirty Tigers outgrew its perch at the top of 1604 Eighth Ave. S., the 106-year-old building that also houses Grimey's and The Basement, and announced a move the same week that WXNA was looking for space. The station struck a deal with building owner Steve West, and volunteers got busy transforming two offices on the top floor into a broadcast suite and recording room where DJs can pre-record a show or a band can perform, as long as they don't mind schlepping their gear up four flights of stairs.

Typical of this project — "The world just keeps almost ending," laughs Crownover — once WXNA's studio was firmed up, the search for a broadcast location hit a snag when their first-choice site, a piece of industrial property in Germantown, was sold. Paul Williams, their FCC-rated consulting engineer, had already done the mandatory study certifying that their broadcast from that location wouldn't interfere with any other signal. Now they needed his help to find another site within three-and-a-half miles of the place specified on their application.

The site they found — a rented space on a broadcast tower on Jefferson Street just east of the Cumberland — turned out to be even better. Because of interference from the nearby bridge where I-65 and I-24 split to circle downtown, the FCC allowed them to raise their antenna to almost double its original height.

From 240 feet in the air, just below the aircraft warning flashers, Williams expects WXNA's broadcast to come in loud and clear everywhere inside the loop created by Briley Parkway and I-440, from North Nashville to 12South to the East Side, though listening to the test broadcast suggests the signal could reach as far south as Antioch. Right from the start, the station has the potential to be a gift for the whole city.

WXNA had plenty of proof of concept — a successful Kickstarter, generous donations at Record Store Day DJ booths from newcomers who'd never even heard of WRVU — but if they needed anything further, they had only to look at the response to their call for volunteer DJs.

More than a hundred people were eager to give up an hour or two each week — and volunteer for studio chores, future pledge drives and more — just to play records for other people. With preference given to those who had previous experience, the final cut still includes more than 80 DJs, plus several trainees who will get a shot on the next schedule.

"[I was] pleased by how many people got what we were wanting to do rather than just submitting shows that seemed too obvious or mainstream," says Randy Fox, WXNA's programming director (or Programming Hepcat, according to his business card).

Count among them masterfully nuanced musicians like Paul Burch, Fats Kaplin and Kristi Rose, Tommy Womack, David Olney and Sam Smith, playing everything from pan-American roots music to film soundtracks. Look for music industry lifers like veteran interview host Peter Rodman and Sundazed label chief Bob Irwin, as well as DIY venue manager and concert booker Kathryn Edwards and up-and-coming rocker Asher Horton. There are surveys of jazz from swing to contemporary, along with experimental music, Celtic tunes and flavors of electronic dance from darkwave to Hi-NRG to house.

You can hear a smattering of talk, too, from comedians Mary Jay Berger and Chad Riden covering the stand-up scene to Dawn and Gene Kote's food show Yum Yum Eat 'Em Up! and Laurel Creech's All About Nashville, which promises Friday lunchtime chats with "unsung heroes improving our city every day."

Fox says he'd like to see more of this kind of programming in the next schedule, especially focusing on arts, culture and public affairs, as well as some more late-night shows. (Currently, their computerized autorotation system, dubbed Bender the Bopper, is scheduled to conduct his Robot Overlord Dance Party most nights from midnight to 7 a.m.) Fox is also mulling a concept he calls "Ken Burns" shows — short-run miniseries on a specific genre or topic. If you have an idea for something cool or weird, he says, let him know.

There's a slate of Aughts-era WRVU classics, too, like Janet Timmons' music discovery showcase Out the Other, Grimey's co-owner Doyle Davis' hip-dipping power hour D-Funk, and Hipbilly Jamboree!, the rockabilly and country odyssey that Fox and his co-host Kels Koch took over from Davis in 1997.

As the sign-on date nears, conversations with WXNA's board members resemble talks with expectant parents who are pacing the floor. Each reacts a little differently — Grigsby with implacable calm, Crownover with infectious and barely contained effervescence.

Pete Wilson, who along with his duties as music librarian will be bringing back his deep-dive proto-rock 'n' roll program Nashville Jumps (as well as hosting three other shows), is quietly excited about getting back on the air. His explanation why highlights exactly what community radio has to offer that — even more than the music — you just can't find anywhere else.

"Less so now, but right after they shut down WRVU, it just felt kind of weird listening to music because I had no purpose for it," he says. "Before, I'd be listening to music and thinking, 'What am I going to be playing on the air?' ... Then when I had nothing to put it on, it kind of felt weird. Like, 'What am I doing this for? Why am I listening to this music?' It's kind of silly, but it really was like that for a while. Eventually, I got so I could sort of enjoy it for the fact of listening to it and keeping it for myself, but I was really wanting to share it and literally broadcast it — to get it out to a wide range of people and say, 'Isn't this great?' "

Though the community station's grassroots gestation is distinctly different from that of WRVU, the first song to play on WXNA will be something to mark the continuity between the two. Since Wilson was the last DJ to broadcast on WRVU's signal, he has the honor of throwing out the first pitch. He has a candidate in mind for the first song, and he's given a hint as to what it'll be.

"I can tell you what it says. It's about making connections with people, and even if it's just for a moment, it's a good thing. It's about getting something off the ground. See if you can figure it out."

Email editor@nashvillescene.com