See also: "Eight Commodores to Watch."

Vanderbilt University athletic director and vice chancellor Candice Storey Lee’s spacious office sits on the second floor of McGugin Center on Jess Neely Drive. It’s just across from Charles Hawkins Field — Vanderbilt’s storied baseball diamond — behind the John Rich Complex, which includes football practice fields. Every day she is surrounded by names. Some, like midcentury football star Jess Neely, served in the same role as Lee — athletic director — while others won significance in the world of Vanderbilt sports with standout athletic accolades and multimillion-dollar donations.

Down the block stands the recently named David Williams II Recreation and Wellness Center, the university’s catchall fitness facility for climbers and swimmers and stressed college students. Williams, a trailblazing Black athletic director like Lee, died abruptly, soon after formally retiring as Vanderbilt’s vice chancellor and AD. That was almost seven years to the day before the Scene’s conversation with Lee. Williams hired Lee, then captain of Vanderbilt’s SEC-championship women’s basketball team, as an intern more than 20 years ago.

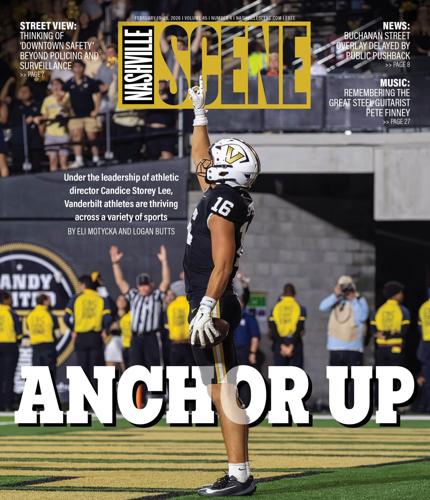

A year after Williams’ death, Lee succeeded him atop the university’s athletics program during a period of drastic change. After decades of streaky Commodore teams finding fleeting success, Vanderbilt now has national contenders in all four major college sports — football, women’s basketball, men’s basketball, baseball — at the same time, and all in the nation’s most competitive conference. Discus thrower Veronica Fraley represented the United States at the Paris Olympics in 2024 within months of completing her Vanderbilt education.

These Vanderbilt athletes are thriving across a variety of sports

New transfer rules and court cases brought by college athletes, including Vanderbilt football’s star quarterback Diego Pavia, helped usher in the NIL era (allowing these athletes to profit financially with their name, image and likeness). Universities have scrambled to build programs in this new legal and financial landscape, where athletes can sign six- and seven-figure contracts before going pro. (According to a source familiar with his NIL contract, Pavia earned a little more than $1 million this season.) Money has flowed from donors to athletes via intermediary entities like Vanderbilt’s third-party collective, the Anchor Impact Fund, which disbursed more than $3 million in 2023 and 2024 according to the most recent tax filings. Unlike many pro sports deals, NIL contracts are private. On Feb. 4 the university announced “Anchored for Her,” a $50 million fundraising effort to support Vanderbilt women’s sports. Vanderbilt announced on Feb. 12 that it would dissolve Anchor Impact and manage NIL via Anchor Advantage, a new in-house initiative.

Success has also brought more dollars and attention to Vanderbilt sports. The elite academic institution enjoys a wealthy alumni network, and fundraising and revenue generation have gotten even more creative, from gimmicks to entire reward systems. After scoring a major football upset against Alabama during the 2024 season, Vanderbilt auctioned off pieces of its goalposts, capitalizing on a fan frenzy. Also in 2024, the university launched a “Priority Points” system that resembles a new currency for donors hoping to get better access to games and tickets. Vanderbilt has upgraded football, basketball, tennis and baseball facilities with state-of-the-art amenities that rival professional sports complexes.

Lee can’t write down the winning formula, but she isn’t surprised by the school’s overwhelming athletic success either. She gives credit to Williams for building a culture of integrity that prizes the student-athlete experience. Resources, like money and new facilities, have helped Vanderbilt attract and retain talent.

Like the rest of Commodore Nation, she’s also taking time to enjoy the show.

Candice Storey Lee

What was it like going from working in David Williams’ athletic department to leading Vanderbilt athletics yourself?

David gave me an opportunity in 2002. I had just finished playing, and he said, “Hey, I’m starting an internship program and I want a former student-athlete.” I didn’t know him, someone had recommended me — I hope because I took great pride in the student-athlete experience and was heavily involved in the community. It was actually an internship not in athletics, but in student affairs, because David was vice chancellor for student life at the time too. From the time I was an intern to deputy athletic director, 18 years later, I always reported directly to David Williams. One of the greatest gifts he gave me — and he gave me a lot of gifts — was the gift of just exposure. To meetings, to people, to his thought process. He gave me his time so I could ask questions, and he was unusually vulnerable. He would say to me, “Have you ever thought about being an athletic director?” It didn’t occur to me. Other than him, I had not seen a lot of African Americans in the role, and certainly had not seen women in the role. Sometimes people have to see things in you before you see it in yourself. A couple times I was thinking about leaving Vanderbilt for the chance to have new role, new responsibilities, but I was getting that here.

What are some specific philosophies or lessons, influenced by David or otherwise, for finding success here?

I often wish that I could just sit with David now, having been in the role for almost six years. I did not realize how many balls he was juggling, and that’s coming from someone who saw him every day. He was purposeful in everything and fiercely believed in the things he believed in. I believe fiercely, deeply, in the student-athlete experience and what sport can do for young people. If you can take that and also take a Vanderbilt degree, you can change the trajectory of your life. Yes, we have to modernize our approach all the time, there’s NIL and much more money in it, but every decision that I make is values-based, every single time. I’ve learned that part of being a leader is, your comfort comes last. I also believe in the importance of showing up. I try to be a lot of places, I try to make sure our student-athletes know who I am, I try to make sure our coaches know that I care about what they’re doing, I try to give my attention to as many alums as I can. I laugh a lot — you can hear me laugh all the way down the hall. We’re gonna approach a job with joy and work really hard.

What have been the hardest decisions you’ve made here?

Every time I’ve made a coaching change. Some people may think that’s easy. You look at the record and you make a decision. Winning is a part of it, but it’s not all of it. Your job as the athletic director, of course, is leading the department, but it’s more than that. From a head-coach standpoint, I want to create a vision, unlock the resources and remove the impediments to give our coaches a chance to take their vision, marry it with mine, and we go. If you’re gonna do that well, you’re investing in people. We’re cultivating real trust and relationships here.

Let’s use women’s basketball as an example. It’s a historic program — you were even a part of it — that has recently, quickly, gone from the bottom of the SEC to a top-five program in the country. What happened there?

Women’s basketball team took down No. 4 Texas Thursday night, elevating the program as a title contender

I’ve hired seven head coaches in six years: football, men’s basketball, women’s basketball, men’s tennis, women’s tennis, volleyball and track. With women’s basketball, people always ask, because I came from that program, was it more meaningful? I wouldn’t say that my responsibility is for everybody, but emotionally, it runs deep on a personal level. I am an alum of the program, and we were very good. We won an SEC championship, we went to two Elite Eights, we were number one in the NCAA tournament one year. When I go on a coach search I think, “I’m gonna know it when I see it.” I talked to [women’s basketball coach] Shea Ralph the very first day that I began my search. She and I are the exact same year, and she was the best player in the country. I immediately felt like this is somebody that’s gonna be easy to lock arms with and to not just meet what we used to have, but surpass it. To be honest with you, I have felt that with every coach I’ve hired and with every coach we’ve been able to retain here.

Shea’s one of the best to ever do it. She’s got high basketball IQ, an incredible relationship-builder, a great ambassador. She checks every box. Then, unlocking the resources is about facilities, ensuring that she has what she needs operationally. The recruiting had to catch up, but her vision was always very clear. I was proud of her when she was in the [Women’s National Invitation Tournament] just like I’m proud of her now.

Is it not a surprise to you that so much success has come so quickly?

Everybody that’s here, I brought them here to win. I want to win. They want to win. The fact that we have aspirational visions, that’s not surprising. I can never predict how long it might take us to turn a corner, because breakthroughs are dependent on so many things. Some that are within your control and some that are not. But I’m really not surprised. I’m excited. I’m delighted when we have big games — I’ll be watching the women’s game against Oklahoma during some SEC meetings tonight, we’ll all be watching. Part of it is having great players like Mikayla Blakes, Aubrey Galvan and Sacha Washington.

Do you have similar stories about football coach Clark Lea and men’s basketball coach Mark Byington? It seems like you flipped a switch and men’s basketball came back in the top 15 and football took a huge stride. Baseball continues to be an exceptional program.

Yep. It’s the same thing. The template is the same. We’re trying to create conditions for success — and yes, sometimes you lose. I can’t guarantee you win every game. You need the right leaders. Support from the chancellor, myself, great coaches. Full alignment to unlock resources. Fundraising and also facilities, operational support, time and access. And a culture of clear communication and young people who deeply believe — stubborn enough to believe when no one else believes and yet humble enough to say, “Maybe we gotta do something a little different.”

Your tenure has completely overlapped with the NIL era, a massive shift in college sports. How does that factor into the way a top-tier athletic department is run?

You still have to be able to identify people who fit your system, but roster development and roster acquisition is a new muscle for a lot of coaches. NIL is very much tied to how you build your roster, so we had to put resources into that. People can build and rebuild rosters in the blink of an eye now. Earl Bennett, he’s our executive GM, he leads a new division for us called the Roster and Finance Division, which is responsible for making sure that we’re staying within the revenue share cap from the House settlement, and oversees all of our revenue share agreements, oversees NIL, is directly connected to the sports that are sharing revenue.

It sounds like your success has come from constant experimentation.

We have had to embrace NIL. It’s the only way. The job of AD is changing — it’s always been to fundraise and hire coaches, but now you gotta think about revenue generation differently. Really, since COVID, we’ve been building the bridge while we cross it. We are not professional sports. You can take elements from professional sports and infuse them into a higher-education landscape — that’s what we’re doing — but I’m really careful with my language there because we don’t consider our student-athletes employees, and we don’t want to be professional sports.

Does that mean higher-revenue sports, like football and basketball, become more important to the university?

We might be talking about more money being infused into the system now, but that allocation is not a new problem. David Williams had to do the same thing as AD. There’s not limitless resources, and we invest where we can get the biggest return, but that’s not always financial returns. It could be supporting our core mission, or values. The biggest change is that we have to be much more diverse in our revenue now — you can’t meet the need by just relying on philanthropy or media rights.

Even five or 10 years ago, Vanderbilt was bottom of the table in the SEC. What do you credit for the athletics turnaround?

Clark Lea says all the time: “We’re one of one.” It is objectively true that we are the only school that has this type of academic distinction in the SEC. I want the high academics. I was drawn to Vanderbilt for that reason. I’ve always believed we could do what we’re doing. We under-invested in athletics for a long time, it’s true. There might’ve been a fear that if you invested in athletics, it might take away from the academic distinction. I’d love to sit with David Williams and say, “Can you believe this?” I know he wanted it, and I don’t know what he was dealing with, why the resources weren’t unlocked for him. You gotta believe it when no one else believes it. Not only did we have believability, but we actually had tangible resources and the courage to try some stuff. But man, it’s not magic. We want to be great at everything.