Mickey Guyton

Mickey Guyton is everywhere.

In February, the country singer-songwriter’s single “What Are You Gonna Tell Her?” called out country music’s long-standing misogyny and subsequently lit up the 2020 Country Radio Seminar. It was both a capital-M Moment for Guyton, who’s been trying to make a name for herself in Nashville for more than a decade, and a hopeful sign of things to come. What came next, however, was COVID-19, which sent the music industry and the rest of the global economy into uncharted waters.

It might have felt safer under these circumstances to back away from the social justice platform she’d recently built for herself. But following the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and the subsequent protests against police brutality and systemic racism, Guyton stepped up even stronger and spoke up even louder, releasing the heartbreakingly soulful “Black Like Me” in early June.

Buoyed by the runaway success of “Black Like Me” and the modern civil rights movement that is upon us, Guyton has been featured in Rolling Stone, Variety and The Washington Post. She’s been interviewed on CBS This Morning and was invited onto the Meditative Story podcast to discuss how and why she decided to finally embrace her uniqueness in an industry that rewards — practically demands — homogeneity. Through it all, Guyton has talked about sitting back in cutoff shorts and cowboy hats and trying to let the sideways glances and racial slurs roll off her back. She’s talked about her willingness to play the Nashville game even when she’s felt destined to lose.

When I speak to Guyton for this article, I ask about all of this. I ask her if she’s tired of having to work twice as hard to get half as much, tired of being Black in a white world, and tired of having to talk about it all the time. NPR called her “a poised and galvanizing country-pop conscience,” and I ask her about that, too. Why, I wonder, is a woman who’s yet to release a full album — a woman who is undoubtedly carrying the weight of being both Black and a woman in an industry as oppressive as country music — also being looked to as the genre’s voice of moral reason?

“Being country music’s conscience wasn’t my intention, for sure, but a lot of times things going on within the industry get brushed under a rug,” Guyton says. “If a Black woman is saying that white women are discriminated against in country music, how do you argue that, you know?”

To be clear, Guyton isn’t saying that she doesn’t want to talk about issues like racism and sexism in country music. What she’s saying is she feels she has no choice. Put differently, if a Black woman doesn’t scream at the top of her lungs about all that’s wrong in society, do her hurts and pains ever make a sound?

“I’ve seen people try to talk about it and get labeled angry and mad, and I have the ability to do that without sounding angry and mad,” Guyton says. “Did I want to just be like every other country girl and be able to sing a cute song? Yeah. But the standards are different. For some reason, when I am speaking on these issues, I’m listened to. If I speak about cute country songs, I’m not.”

Fall is fast approaching. We are six months into the coronavirus pandemic, and the racial reckonings rippling through every corner of society are showing no signs of slowing. Neither, as it turns out, is Guyton.

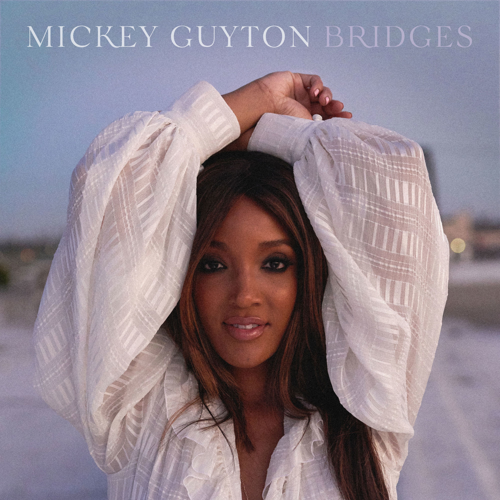

Despite some fans urging country music artists to stick to a benign, music-only script, Guyton’s new EP Bridges, released Sept. 11, doubles down on her desire to build a better world through her art. The record opens with “Heaven Down Here,” Guyton’s current single, in which she laments that “The world is turning upside down / I swear it feels like all we’ve got is problems,” and urges God to let his love rain down “Like pennies / In this wishing well of tears.” In the second track, “Bridges,” she places the onus for healing on mortals, asking: “What if we took these stones we’ve been throwing / What if we laid them down / What if we forget all that we know / And make some common ground?”

“I feel like ‘Bridges’ is the bridge between the songs,” Guyton says. “You have these songs that are speaking about such hard topics, but ‘Bridges’ is like, ‘What if, instead of being so divided, we build bridges?’ ”

This project is classic Guyton — big voice and wide range set to early-Aughts pop production — so the most remarkable thing is, by far, the content of her songs. The fact that a mainstream country artist can spend four tracks of six on an EP talking about anything other than breakups and beer is remarkable. Even “Rosé,” Guyton’s ode to the pink drink of choice for so many women, is less fluffy than it seems.

“I wrote that song two-and-a-half years ago because I couldn’t believe that nobody had written a song about rosé,” Guyton says. “If there’s a drink that’s for women, it would be that. So I brought this song to the label forever ago, and you know,” Guyton pauses, her voice trailing off. “Now they hear me, but they didn’t before.”

If you’ve followed Guyton’s career since, say, 2015, when she released her single “Better Than You Left Me,” or 2016, which brought “Heartbreak Song,” the idea that Guyton’s label Capitol Nashville is listening and letting her be creatively free is welcome and refreshing. The toeing of the line and remaking herself for Nashville’s sake wore heavy, and the intense machinations always seemed evident in her work, her demeanor. Finally, though, it seems Guyton has broken free of the rules and regulations that stifled her.

“This project is completely from me,” she says of Bridges. “I didn’t really have anybody guiding me, or choosing songs, or scrutinizing my work the way I did before. They’ve given me the opportunity to actually be an artist, and I’ve never had that. This is 100 percent from me, and I think the songs reflect that.”

The record also reflects the reality that there is still much work to be done if Nashville is going to build the bridges that Guyton sings about. Though she makes explicit pleas for social justice and reconciliation, each track on the EP, including the autobiographical “Black Like Me,” was co-written, produced and performed by white people.

The fact that Black Nashvillians in creative fields struggle to find opportunities even with successful Black artists in town is a familiar problem. It’s also one that Guyton hopes to address in the future. But first, there is Bridges. As an artist who has yet to break big, Guyton understands the expectations that accompany every project, including this EP composed of songs so close to her heart. The label needs it to do well. Her publisher needs it to do well. Her management needs it to do well.

It is Guyton’s hope, of course, that people relate to — and buy — her music. But the unyielding, self-imposed pressures that have accompanied her past releases are noticeably absent. Guyton is pregnant and due almost a year to the day following her career-defining performance at CRS 2020. That, coupled with an industry in upheaval and lots full of parked tour buses, has allowed Guyton to absolve herself of the worry that typically precedes public reception. For now, all that matters is that she’s created a project that she believes in, and that she feels good about.

“I feel really, really good about it,” Guyton says. “I really do.”