To talk about Los Angeles country-rock is to talk about community. The artists of that scene — which first emerged in the ’60s and saw a massive resurgence in the ’80s, albeit in an evolved form — found success through a wealth of artistic talent, to be sure. Their music drew from West Coast country like the Bakersfield sound as well as traditional bluegrass and early rock ’n’ roll, and they catapulted it from a niche scene to a vibrant, diverse assemblage of country music whose roots extend well into the present day. That’s thanks in large part to a concerted effort by the genre’s pioneers to come together, collaborate and lift each other up.

And what is L.A. country-rock? Take a good look at some of the artists involved: Linda Ronstadt, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Emmylou Harris, Ricky Nelson, The Byrds, Dwight Yoakam, The Blasters, Los Lobos and many more. The classification feels more nebulous with each name-drop, functioning more as an umbrella beneath which genre cross-pollination can thrive than as a fixed categorization. The closest current-day analog might be Americana, though the geographic constraints of Los Angeles country-rock make for a more cohesive movement than the now-international scope of what is currently considered Americana music.

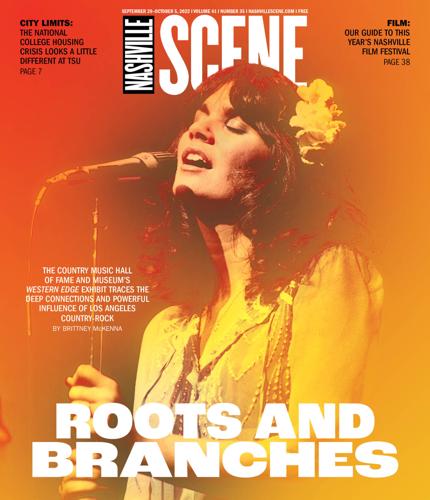

On Friday, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum will unveil Western Edge: The Roots and Reverberations of Los Angeles Country-Rock, which will open with a star-studded concert in the museum’s CMA Theater. Celebrating the heritage of this fertile music scene, the exhibit is the museum’s first new major installment since Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ’70s opened in mid-2018. It’s a deeply researched, decades-spanning collection that focuses primarily on the country-rock scenes of the ’60s and ’80s. It also charts the rise of country-rock-influenced commercial pop in the intervening decades, zooming in on acts like the Eagles and some of Emmylou Harris’ later work.

The co-curators of Western Edge are longtime museum staffers Michael Gray, whose title is executive senior director of editorial and interpretation, and onetime Scene staffer Michael McCall, who is senior editor-writer. They drew from hours of interviews with members of the scene, amassing more than 100 artifacts on loan for the three-year exhibition and sharing their own individual wealth of personal knowledge of and passion for the music in question.

“I graduated high school in 1975, so this was the music of my youth,” McCall tells the Scene. “At least it’s the beginning of it, especially as you get into Neil Young and Crosby, Stills and Nash, and Ronstadt. I had a lot of these albums on 8-track. [Laughs] Then I lived in San Francisco in the ’80s, so Los Lobos and The Blasters and Lone Justice — all those bands were coming up to play and playing in San Francisco.”

“The Blasters were a big part of my entry point into country music,” Gray adds. “Getting into The Blasters got me into rockabilly, which got me into country music, which led to my job [at the museum]. So, they were a good gateway for me into roots music and country music. I’d say right around that same time I was getting into Los Lobos. And when I discovered Sweetheart of the Rodeo in high school, it really opened me up to country music, and to The Byrds’ music.”

McCall and Gray began planning the exhibition in late 2019, following an artist-in-residence performance at the museum by Marty Stuart that included The Byrds’ Chris Hillman and Roger McGuinn as guest artists. Gray and McCall traveled to Los Angeles in early 2020 to secure artifacts, to visit key scene sites like long-running venue the Troubadour and to conduct interviews with artists like Hillman (who also played in The Flying Burrito Brothers, Stephen Stills’ supergroup Manassas and The Desert Rose Band) and pedal-steel guitarist JayDee Maness (whose résumé includes Gram Parsons, The Byrds and Vince Gill). As the familiar story goes, the COVID-19 pandemic quickly made further travel next to impossible for several months, leading the team to pivot to virtual research and conversations.

Fortunately, many of the exhibition’s featured artists now live in or frequently visit Nashville, allowing the team time and access to interview Emmylou Harris, Taj Mahal, Graham Nash, J.D. Souther, Rosie Flores and many more artists key to the formation of country-rock. Many of these extensive interviews — a total of 23 as of press time — will be available in video form as you navigate the exhibition, adding intimate firsthand context to an already impressive collection of physical artifacts. Among those are instruments, stage clothing (Nudie Suit fans, get ready to be dazzled, pun intended), original show posters, handwritten lyrics and previously unseen photographs.

It’s hard to choose a handful of highlights from the truly astounding collection of artifacts, but lay country fans and genre obsessives alike are sure to find pieces from country-rock history that speak to their interests. The late Gram Parsons’ famed Nudie Suit from the cover of the Burritos’ 1969 debut The Gilded Palace of Sin — the white one with the marijuana leaves, pills, naked woman and enormous cross — is on display next to Hillman’s brilliant blue suit and the black one that belonged to “Sneaky Pete” Kleinow. They showcase the craftsmanship of creator Manuel Cuevas as well as the personality of each band member. (For the completists, Chris Ethridge’s suit, white and decorated with roses, is unfortunately lost to history.)

A signature look from Dwight Yoakam — a Manuel-designed, rhinestone-studded bolero jacket and a Stetson hat — connects the style of the ’60s to that of the ’80s, with instruments like Yoakam’s 1989 Martin HD-28P guitar on display, too. Each member of Los Lobos has an instrument featured, like the custom jarana jarocha built for Louie Pérez by Candelario “Candelas” Delgado, whose son Manuel Delgado operates Delgado Guitars in East Nashville.

“That guitar just reeks of history,” says Pérez. “Candelas Guitars was a fixture in East Los Angeles. It served mostly mariachi musicians. We were rock ’n’ roll kids and we knew it was there, but when we had our own renaissance and discovered the music of our culture, we were looking everywhere for these instruments that we would see on the cover of these old records. So where did we go? We went to Candelas Guitars and talked to Candelario. We said, ‘Hey, we’re local rock ’n’ roll guys. We’re not the type of people you would usually work with. But we’re really interested in this.’ He was impressed by that and helped us out. … Because of him, we were able to get through those early years of learning the traditional music of Mexico.”

While assisting in the creation of the exhibition, Hillman told the museum that he viewed the term “country-rock” as “a device to sort of pigeonhole you into a more descriptive place. It’s country music to me, you know. It’s all country music to me — or music.” It was a bit of a revolutionary term at the time of its coining in the early ’60s, as rock ’n’ roll was still relatively new — several artists featured in the exhibition, including Hillman, cite Elvis Presley’s 1956 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show as a critical influence — and hadn’t yet made its way into stricter scenes like bluegrass and folk.

That would soon change as artists like Hillman, Parsons, Ronstadt and Ricky Nelson began experimenting with the boundaries of country and bluegrass, eventually deciding to eschew those boundaries altogether. This spirit of innovation spread like a virus, and soon aspiring artists were flocking to Los Angeles, hoping to be part of a musical movement unlike anything they had seen before.

Country-rock’s bluegrass roots can’t be ignored, as pivotal figures like Hillman and Clarence White cut their teeth playing traditional bluegrass. Many artists especially cite The Dillards — the bluegrass project of Doug Dillard, Rodney Dillard, Mitch Jayne and Dean Webb — as integral to bringing bluegrass into country-rock. This is particularly due to the band’s dynamic live shows, which bucked the traditional bluegrass performance style in favor of movement and interaction. They’d soon land a role as family band The Darlings on The Andy Griffith Show and bring their influence to a broader audience.

“Before it was full-blown country-rock, it’s these young bluegrass bands, like The Kentucky Colonels and The Dillards and The Scottsville Squirrel Barkers,” Gray explains. “And Chris Hillman is just right there as a teenager, playing mandolin in these bands. Next thing you know, he’s in The Byrds, and ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ is, in some ways, the big bang of folk-rock, bringing rock and folk music together like that.”

Another pivotal force of the ’60s scene was Parsons, whose Boston-born International Submarine Band relocated to Los Angeles later in the decade, not realizing the massive impact that move would soon have. Parsons met Hillman soon after landing in L.A., a connection that led Parsons to joining The Byrds, to whose country-rock landmark Sweetheart of the Rodeo he contributed; for this, the exhibition features Parsons’ 1963 Martin 00-21. His tenure with The Byrds lasted only for a couple years, and Parsons’ next project, The Flying Burrito Brothers, also involved Hillman and continued the sonic evolution of country-rock. Since Parsons’ death at age 26 in 1973, California’s Joshua Tree National Park — the site of Parsons’ impromptu cremation, overseen by friend, road manager and longtime East Nashvillian Phil “The Road Mangler” Kaufman — has become something of a spiritual site for music fans, still attracting artists and country lovers to this day.

Parsons’ collaborations with Emmylou Harris, as on his albums GP and Grievous Angel, helped launch her solo career, and she found commercial success in the mid-’70s backed by a group called The Hot Band. Several of Harris’ items are featured prominently in the exhibition, including her 1955 Gibson J-200 and a Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors cowgirl outfit that was originally made for Annie Oakley television show actress Gail Davis.

“Emmylou has had such an influence on so many musicians, within country music and beyond,” McCall says. “I wasn’t buying country music when I was a teenager, but I bought Emmylou Harris records. Then she ends up living in Nashville and leading this outstanding band that went on to have great impact in Nashville, from Ricky Skaggs to Rodney Crowell to Tony Brown.”

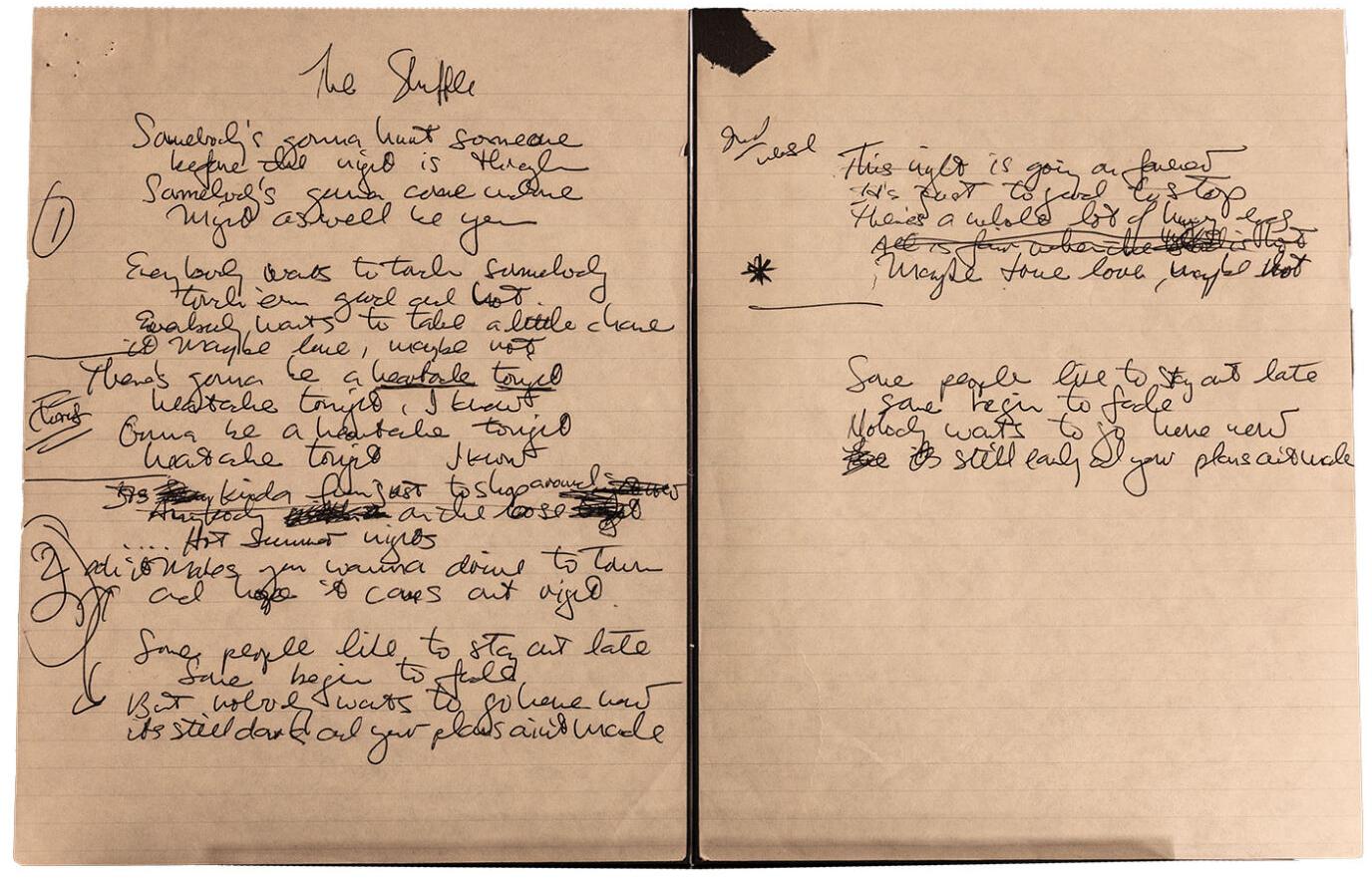

Harris was not the only artist to find commercial success within country-rock, as acts like the Eagles brought the genre’s sounds — albeit often slicker versions of them, and, depending who you ask, somewhat watered-down — to mainstream audiences through hits like “Take It Easy,” “Tequila Sunrise” and “Peaceful Easy Feeling.” The exhibition includes handwritten lyrics for songs like “Best of My Love,” a co-write between J.D. Souther and the band’s Glenn Frey and Don Henley, and “New Kid in Town.” One of the most fascinating instruments on display is Eagles co-founder Bernie Leadon’s modified 1962 Fender Telecaster, which he played on the studio recordings of the Eagles’ “Take It Easy,” among other hits. Its hollowed-out body makes space for a B-bender mechanism that mimics the sound of a pedal-steel guitar — a modification pioneered by another Byrds member, Clarence White.

Lyrics to the Eagles’ “Heartache Tonight,” originally titled “The Shuffle”

Though country and roots music found welcoming homes in places like Nashville and Austin, Texas, Los Angeles was, surprisingly to some, uniquely suited to become a crucial hub for country-rock. Hollywood’s establishment of L.A. as an entertainment-minded city made space and resources for creators of all kinds, with its artistic reputation drawing not just actors but musicians, writers and industry hopefuls.

And California’s own long-established country music scene was anchored not just in Bakersfield to the north but within Hollywood itself — Gene Autry, after all, found success as a “musical Western” star following his cameo in the 1934 film In Old Santa Fe. Following an influx of post-WWII transplants to California, many of whom were country fans if not artists themselves, Hollywood’s Capitol Records began signing country and Western artists. Among the first were Tex Ritter, Merle Travis and Tennessee Ernie Ford; nearly a decade later, Buck Owens and Merle Haggard would follow.

As the country-rock scene began to grow, venues increasingly became crucial meeting points for both aspiring artists and industry executives hoping to find the next big star. One venue that became pivotal to the development of artists from both eras was The Ash Grove, a folk-music club in what is now considered West Hollywood. Los Angeles native Ed Pearl opened the club in 1958, naming the venue after a traditional Welsh folk song. The club was badly damaged in a series of fires, acts Pearl believed were arson in retaliation for his unabashed activism in the face of the Vietnam War. It closed soon after one such fire in 1973; on the site today is the L.A. outpost of comedy club The Improv.

“The first musicians I saw live in Los Angeles were Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder — together in a band called the Rising Sons — at The Ash Grove,” Ronstadt writes in her foreword to the exhibition’s official catalog. “They had the Grove in their pocket. At that point I had never heard anything of quite that quality.”

The Troubadour, still going strong on West Hollywood’s Santa Monica Boulevard to this day, was a crucial hub for the burgeoning country-rock scene in the ’60s. The club’s Hootenanny open-mic on Monday nights drew throngs of musicians, fans and industry types, with each participating artist performing three songs — that is, if they weren’t booed offstage first. If an open-mic set went well, performers caught the eye of record executives and more established artists, making connections that on several occasions led to real success.

Linda Ronstadt at New Victoria Theatre, London, England. Nov. 13, 1976.

For Linda Ronstadt, the Troubadour played a major role in her decision to pursue music at all. When the now-icon was just 18 years old, she traveled to Los Angeles to visit a friend and found herself at this buzzed-about club in Hollywood. The Byrds played that night and Ronstadt was mesmerized; soon after, she dropped out of the University of Arizona and made her way back to L.A. The support of the community and its commitment to pushing the musical envelope greatly informed the sound she would develop as an artist.

“I recorded ‘Everybody Loves a Winner’ back in those early days,” Ronstadt writes, in the same essay. “The record had pedal steel guitar and bluegrass harmonies on top of an R&B rhythm section. That kind of approach came out of the routine creative exchanges we had going on in L.A. We all hung out at the Troubadour and jammed together, united by our mutual desire to weld country music songs and harmonies to an R&B — or rock and roll — rhythm section.”

By the time artists in the ’80s began revisiting this music — and rejecting the heavily commercial country-rock taking over radio charts — the venue landscape had changed, but the deeply rooted sense of community had not. The Ash Grove was gone, but the Troubadour remained, and venues like Whisky a Go Go and the Starwood created alternate spaces for artists to meet, collaborate and grow their followings.

The ’80s country-rock scene greatly benefited from cross-pollination with L.A.’s thriving punk scene. Punk groups like L.A.’s own X and London’s Public Image Ltd (aka PiL, fronted by former Sex Pistols singer John Lydon) became friends and collaborators of many country-rock acts, like the delightfully unclassifiable The Blasters. Their guitarist Dave Alvin especially found community in the punk scene and used the success of The Blasters to lift up artists like Los Lobos.

Los Lobos, Dwight Yoakam and his band in Palo Alto, 1984

“In the ’80s, there was a second community that came out of the Hollywood punk clubs,” Gray explains. “We have these wonderful pictures of The Blasters and Los Lobos, just hanging out together. The pictures are just so alive with, like, you know, Dave Alvin and Phil Alvin hanging out with David [Hidalgo] or Cesar [Rosas] of Los Lobos, and they’re showing each other their instruments and they’re sharing stages.”

Pérez shares that he was playing a traditional instrument, though not the jarana in this exhibit, at what he calls the band’s “coming out” show at the Olympic Auditorium, opening for PiL. “They had to pick a venue where no one could break anything,” he explains, laughing. The punk fans in the crowd didn’t take kindly to Los Lobos’ traditional sound, and Pérez says he “could feel the air moving from some thousands of middle fingers going up at the same time,” and that the crowd “threw everything they could get their hands on at us.”

Contemporaries of Los Lobos, The Blasters experienced similar reactions from punk fans at the outset of their career. The Fender Mustang that Dave Alvin lent to the exhibition is still studded with shards of glass from beer bottles flung by angry punks. Soon, though, the country-rock and punk scenes found common ground, and even began helping one another navigate the crowded musical landscape. Alvin played briefly with X, and also started country-schooled outfit The Knitters with X’s Exene Cervenka, John Doe and D.J. Bonebrake; bassist Jonny Ray Bartel of The Red Devils rounded out the lineup.

“With The Knitters, we were doing things like ‘Silver Wings,’ though granted, perhaps, we weren’t doing it as well as Merle Haggard,” says Alvin. “But we were enthusiastic. And what happened, I think, for a lot of punk rock kids was, ‘Hey, this is pretty cool. I like this.’ Or, ‘My granddad listened to this, my sister listened to this. This is cool.’ We made it cool for certain people of a certain age group in the early ’80s to experience country music positively for the first time.”

It wasn’t long before ’80s country-rock found its way to the mainstream too, particularly through the success of artists like Yoakam, Ronstadt and Hillman. Hillman and The Desert Rose Band even traveled out to Nashville to perform on the Grand Ole Opry. After that performance, Opry staff guitarist Jimmy Capps told the band’s Herb Pederson, “It’s funny that it would take two guys from California to show Nashville what country music is supposed to sound like.”

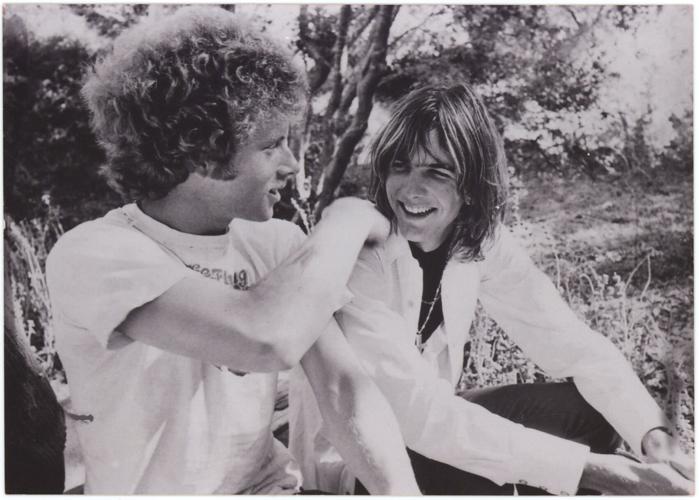

Chris Hillman and Gram Parsons, 1969

If it sounds like Chris Hillman runs through the entire exhibition, it’s because he does. The official catalog for Western Edge calls the San Diego-born multi-instrumentalist “the linchpin,” and it’s hard to argue with that assessment given his omnipresence through the scene.

When Ronstadt saw Hillman playing with The Byrds, she recognized him from his earlier gigs with ’grassers The Scottsville Squirrel Barkers. As she writes: “I thought one day, ‘Well, if he can change from mandolin to electric bass and be folk-rock, then [my band] the Stone Poneys can do that, too. ”

Hillman’s musical talent was immediately apparent to anyone who encountered him, including Bill Smith, a custodian at San Dieguito High School who was also a musician and became one of his first mentors. When Hillman was just 16 years old, his father died by suicide, giving the mentor relationship new layers of meaning. Hillman and Smith remained in touch until Smith passed from complications due to Parkinson’s disease in 2017. Then, Smith’s wife presented Hillman with his 1958 Martin D-28, a particularly meaningful piece of Hillman’s on view in the Western Edge exhibition.

“He started taking me under his wing, and showing me guitar stuff and guitar styles,” Hillman says. “And he knew that I really liked bluegrass. And that was cool, because he was basically a country singer. … I hadn’t seen him for years, and one night The Desert Rose Band is playing. It was 1986 or ’87, and we’d had some success on the radio. And out in the audience is Bill and his wife Darlene. And I said, ‘Bill!’ And he said, ‘I’ve been watching you. I’m really proud of you.’ … I went to see him a week before he died and sang some songs … and I told him, ‘If I hadn’t met you, and you hadn’t helped me out when my dad died, I don’t know what would have happened to me.’ ”

The full scope of Hillman’s influence is difficult to sum up. Dwight Yoakam, writing in the foreword to Hillman’s excellent 2020 memoir Time Between, gives it a try. “In spite of Chris’s varying degrees of chagrin through the years at being given the title,” Yoakam writes, “to me and millions of other fans, he will remain forever immortal as one of the principal architects and a founding father of country-rock.”

Whether Hillman would agree with this sentiment is another story. “I give great credit to Ricky Nelson,” he says. “He was doing country-rock in the sense of ‘Hello Mary Lou.’ That’s pretty straight-on, if you want to label it as country-rock. So he was ahead of all of us. And he stayed true to his guns. His stuff was just brilliant.”

In the exhibition catalog, an essay defining country-rock concludes thusly: “The first country-rock song according to Hillman and Yoakam? Rick Nelson’s 1961 hit ‘Hello Mary Lou.’ ” Artifacts of Nelson’s in the exhibition include handwritten lyrics to his 1972 song “Garden Party” and his 1969 Gibson Les Paul Custom.

Accordingly, Hillman is not just a throughline within the exhibition but also helped to bookend it. He was one of the first artists interviewed for the project; his wife, Connie Pappas Hillman, was invaluable in gathering artifacts and information for the exhibition. As the museum sought a natural ending point for the display, which proved difficult in light of the scene’s many meandering paths outward, Gray and McCall landed on Hillman’s late-’80s commercial country success as a marker for the end of this era and the start of a new one.

Several veterans of this scene see similarly exciting invention happening among today’s roots and country artists. Billy Strings in particular stands out to Hillman, who says of the rowdy young singer-songwriter-guitarist, “I think he’s really drawing on old bluegrass, but he also is very well aware of all kinds of music, and incorporates heavy metal, all this kind of stuff is good.” Pérez cites bluegrass guitarist Molly Tuttle as an especially exciting young act, saying of her, “She is something else. Listening to the stuff she’s playing, it’s like, ‘My goodness, who can pick like that?’ And she’s also writing these intensely personal songs.” Alvin was reluctant to name any specific artists for fear of leaving anyone out, but noted that today’s batch of up-and-comers has him feeling as optimistic as ever.

The exhibition itself makes Alvin feel hopeful for country music, too.

“In the past, there was a sort of rivalry between the West Coast scene and Nashville,” he says. “And to me, music is all about connections. So an exhibition about the connection between Tennessee and California, between rock and roll and country, between the Pacific Ocean and the Cumberland River — they may be 2,000 miles apart, but there’s certainly cultural connections that I think have been overlooked.”

It feels only fitting to let Hillman have the last word. Sharing his thoughts on the state of country and roots rock today, he offers a simple, emphatic answer: “This music is alive and well.”

Linda Ronstadt at New Victoria Theatre, London, England. Nov. 13, 1976.