On Tuesday, June 5, 2001, Margot Café & Bar welcomed its first diners into a restaurant created in the shell of a 70-year-old building at the corner of 10th and Woodland in the wilds of East Nashville. The original exposed-brick walls were dressed up with copper cookware and vintage pottery, the tall windows hung with drapes pulled back to the wooden frames, and gleaming tables set with fresh flowers or herbs placed against banquettes on either side of the polished concrete floor. That night, chef-owner Margot McCormack and her staff — visible through the pass into the tiny kitchen — cooked for 120 people, each of whom reserved one of 75 seats in the main dining room, at the petite comma of a bar or on the mezzanine.

That figure will undoubtedly be eclipsed on Friday, June 5, 2026, when — after 25 years and multitudes of cheese plates, bottles of bubbles, buckets of Provençal olives, acres and acres of locally grown produce, and untold multitudes of roast chickens and seasonal fruit tarts — the final service will take place.

The momentous decision to close Margot and list the property for sale came in the wake of what McCormack describes as her hardest five years in business. Margot’s Five Points neighborhood was hit by a deadly tornado just past midnight on March 3, 2020, almost immediately followed by COVID chaos — a double whammy that delivered a knockout blow to Margot’s sister restaurant Marché. Then there were personal health issues, head-spinning changes in the Nashville restaurant industry, and the evolution of a quirky, artsy, creative, fiercely independent neighborhood that both nurtured and benefited from Margot.

After the back-to-back blows of the tornado that damaged both of her Five Points restaurant properties and the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, chef M…

McCormack ruefully observes that opening Margot would be impossible in today’s Nashville, but she delights in telling the tale of its scrappy start.

A West Nashville native, McCormack landed her first kitchen job at the legendary — and deservedly infamous — Faison’s in Hillsboro Village, where she was paid $4 an hour. Naturally, that inspired her to make a career of cooking, which led her to the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, N.Y. She then built her résumé in Manhattan and upstate New York restaurants, where she met her future wife Heather Parsons.

In 1995, McCormack returned to Nashville, intent on opening her own restaurant. Step one was reestablishing Nashville connections, starting with taking the chef job at F. Scott’s restaurant. Noting the emergence of independent, chef-owned restaurants in underserved urban neighborhoods (Sasso in East Nashville in 1998, Caffé Nonna in Sylvan Park in 1999, Mirror on pre-12South 12th Avenue in 2000), she moved to step two. Over coffee one morning at nearby Bongo Java Roasting Company with Fred Grgich — who had helped open Nonna — McCormack spied the available building in Five Points; landlord March Egerton gave them a look.

“It was a mess,” McCormack recalls. “The roof had a really big hole in it, and the space was so raw. But I could see it. The first time we walked in, I said, ‘There’s the kitchen, here’s the dining room, there’s the bar, there’s the bathrooms.’ If I can see it, I can do it. I saw Margot.”

McCormack and Grgich persuaded Egerton to renovate the second floor so they could have enough seats to serve alcohol. They brought in Jay Frein, and each of the three put $25,000 in the pot and gave their credit cards a workout. “It cost us about $150,000 to open Margot,” McCormack says. “No one could do that today.”

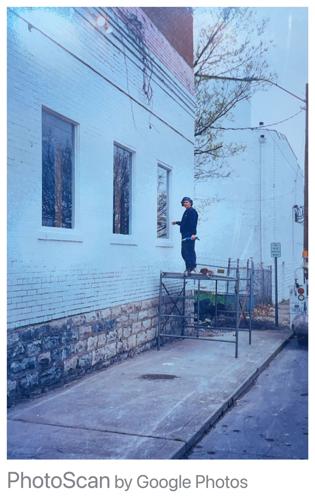

They did a lot of physical labor themselves. Parsons dove into demo and built the bar. As it became clear that something was happening in the former service station, which had been vacant for 10 years, neighborhood residents began poking their heads in, saying hello and bringing welcome gifts.

Margot McCormack

McCormack sought out local farmers to support her intent to change the menu daily. Margot has neither a freezer nor a walk-in, so everything has an extremely short shelf life — what comes in must all go out. Tana Comer of Eaton’s Creek Organics was first. “She came in one day with a basket of her beautiful vegetables that she had picked and washed that morning,” says McCormack. “Everything she brought me through all the years was perfect, and she set the bar for everyone else.”

In the days before social media, the Margot team had to get the word out old-school style, calling contacts on the phone. Once opening night was set, they began taking reservations — also by phone, written down by hand. McCormack had to tell her mother to stop telling her friends, because they were full.

Margot quickly established itself as a culinary destination, neighborhood landmark and growth catalyst. The kitchen was an academy for young cooks, and the front-of-house set the standard for warm and professional service. The bar became known for its unpretentious approach to wine. The restaurant was the site for countless birthdays, first dates, engagements, baby showers and anniversaries, conventional holidays, East Nashville-centric events, Bastille Day and the annual release of Beaujolais nouveau. Plus celebrations of Julia Child’s birthday.

McCormack and Parsons had a commitment ceremony in 2006 — the same year they opened Marché Artisan Foods — had a son, Jacob, in January 2011, and legally married in Cape Cod in 2013.

Key to Margot’s sustainability and McCormack’s physical and emotional health was the arrival in 2011 of young Hadley Long, then a student at a Washington, D.C., culinary school who applied for an externship with Margot. She put him at Marché with chefs Matt Davidson and Kat Britt for a year, before “poaching him” for herself. “He had a burning desire to learn and was just a breath of fresh air,” she says. “He and Kat were just the best, and we had so much fun.”

The 2020 tornado destroyed homes and buildings in the neighborhood and damaged Margot; one of the most enduring images of the days following was the outdoor cookout the restaurant threw for 500 of its closest friends — a beacon of light in the dark. COVID was even more debilitating, prompting layoffs, service pivots, severe financial strain and exhaustion. It was also when McCormack’s wife delivered an observation that broke through. “One day she said, ‘You spend all your good energy at the restaurant, and when you get home, you don’t have anything left for Jacob and me.’ That cut right to my heart.”

An outdoor cookout thrown by Margot following East Nashville's March 2020 tornado

McCormack went in that night and told Long it was her last night shift — that she would work lunch, but he was the guy. In July, 2022, he took over the Margot kitchen as executive chef.

As the restaurant approached another milestone, she again took personal and professional stock. “I’ve spent 24 years in the restaurant looking out the kitchen window at that corner, and I love it, but I’m done,” she tells the Scene. “It’s time. Time for something new, for the building and for us.”

The announcement of Margot’s final service nearly seven months before it actually happens was influenced by the abrupt closure of Marché. “It didn’t get the fanfare it deserved — people didn’t get their last order of French toast or say goodbye to their favorite server. Margot and all our people deserve that.”

So consider the next seven months the Margot Farewell Tour — a last glorious hurrah of one of the best, most meaningful, most generous, impactful and beloved restaurants to ever take residence in Nashville, and act accordingly.

“We’re going to have plenty of celebrations,” McCormack promises. “It’s going to be fun.”