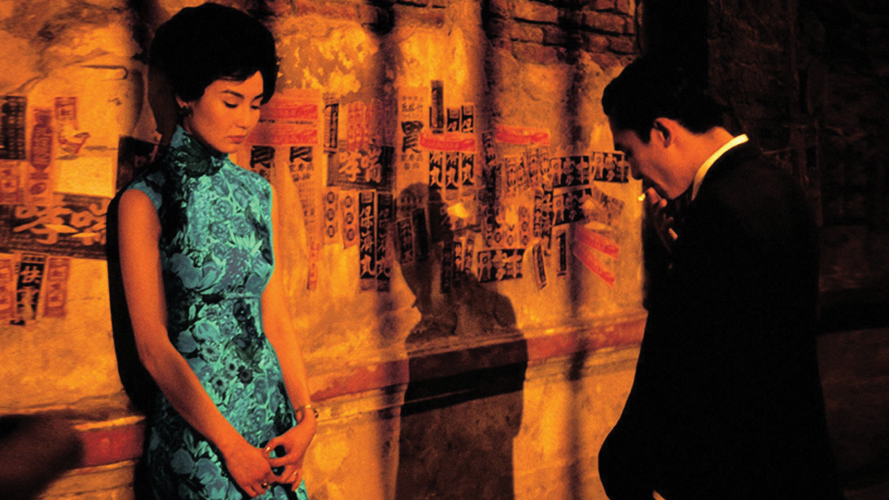

In the Mood for Love

Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar-wai is often spoken of as a supremely sensuous and romantic filmmaker. And it’s true. But more than sensuosity itself, his films study the transient and fleeting nature of romantic experience. A Wong Kar-wai film is even more about the memory of love — unstable and impermanent like a lingering touch or a taste in your mouth that inevitably fades — than the active sensation of love.

Though Wong’s films have not necessarily been impossible to see, previous physical releases of his work are, for the most part, either prohibitively expensive or lacking in quality. The Belcourt’s partial-career retrospective, World of Wong Kar-wai, includes 4K updates of all of his features, from 1988’s As Tears Go By to 2000’s In the Mood for Love (with the exception of Ashes of Time, his adventurous revisionist take on China’s wuxia genre). Also included is an extended director’s cut of “The Hand,” Wong’s segment from the international anthology film Eros, with Steven Soderbergh and the late Michelangelo Antonioni.

These new restorations stand apart in particular because of the extensive, hands-on involvement of Wong Kar-wai himself, who has taken the preservation of his work as an opportunity to execute a few new changes that weren’t feasible at the time of release. Most notable — and perhaps a little controversial to certain hardcore cinephiles — are the tweaks he has made to Fallen Angels, now presented in an entirely new aspect ratio with additional frame-by-frame alteration to the coloring of the film. At the core, of course, it is still fundamentally the same film, and if you’re encountering it for the first time, its vivid passions and kinetic style will be just as striking as they were years ago.

I was surprised — and honestly a little thrown off guard — the first time I saw In the Mood for Love and discovered not a story of a heated and illicit affair, but rather something much more elusive and guarded. But maybe that’s what the title really refers to — being “in the mood for love” is not synonymous with being in love. It is, instead, a knotted swarm of feelings, an atmosphere of anxiety as much as eroticism, as possible lovers dance around an emotion, daring each other to collide. Wong’s true subject matter is not romance but hesitation: secretive whispers, unrequited loves, chance encounters, cosmic coincidences and repressed yearnings. Lovers recollect and recall memories that once felt potent and overpowering, but now seem so much more distant.

Wong is undeniably given the most praise as a visual stylist — his palette has been widely imitated and absorbed by filmmakers over the past 30 years, but there’s no mistaking the genuine article. His camera often feels possessed of a mind of its own, sometimes careful and precise, but just as often jagged and canted. There are the occasional stuttering slow-motion frames, which pull moments out of linear time and briefly take us into a dimension purely defined by emotional experience. Wong’s films are unapologetically beautiful in their cinematography, and they unsurprisingly star some of the most beautiful faces ever put on screen, the finest of a generation of Hong Kong acting talent — Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Maggie Cheung, Leslie Cheung, Faye Wong.

Chungking Express

But what remains with me about the cinema of Wong Kar-wai, long after the memories have dimmed and the images dissolved, is the rapturous sound of it all. Through his soundtracks, Wong truly embodies Hong Kong’s unique historical position at a geographical and political crossroads, a city that absorbs and transforms the many cultures that have passed through it. Almost every Wong film is a living jukebox, each track hand-picked and personally felt by the audiophile auteur. You get the sense that the songs Wong highlights in his films aren’t just needle-drops, or tracks a music supervisor turned him onto; these are songs he has lived with, like the shopgirl who obsessively plays “California Dreamin’ ” in Chungking Express.

The often iconic musical cues in Wong’s films form a wide-ranging songbook — everything from Laurie Anderson (Fallen Angels) to Nat King Cole (In the Mood for Love) to Spanish boleros and tangos (in the Argentina-set Happy Together). But maybe the music that speaks most to Wong’s artistic tendencies are the Cantonese-language covers of Western pop songs that appear in several of his films, like “Take My Breath Away” in As Tears Go By and The Cranberries’ “Dreams” in Chungking Express. His movies are suffused with the melodramatic gloss of a pop song, but reinterpreted and reimagined, familiar and aching yet also uncanny and new.

Because of its highly industrial and technical nature, cinema rarely ever reaches the direct expressive capabilities of music, but Wong Kar-wai plays the camera like a pianist putting his heart on the keys, with only the slightest of barriers between the soul of the artist and the emotions of the audience.