Near the end of the 20th century, when he was 15 years old, Joey Brown stood by his brother’s grave and struggled to breathe.

Joey’s childhood, if you didn’t dig deeper, might’ve seemed like a Tom Petty song. Fair-haired, blue-eyed, good-looking, he grew up poor, raised in the Nazarene Church, working the fields in and around Clarksville for extra money, growing strong as he chopped tobacco in the Tennessee heat. He was the youngest of four, his parents divorced when he was 6, and his mother Brenda remarried when he was 8. Brenda had another child with Joey’s stepfather, and then they opened McCoy’s Market, a bait shop and grocery store out in the country.

In his early teens, Joey was summoned to court. He learned that his father had abused his three older siblings, and that once he remarried, he’d abused his new wife’s children. Junior, Joey’s 25-year-old brother, took the stand and talked about what their father had done to him. For the first time, Joey learned that his older brother was gay. Junior was HIV-positive. And he was dying.

After the trial, in the middle of his ninth-grade year at Northwest High, Joey began to dread cross-country practice. Each day, during long runs with the team, Joey would fall behind and drag himself over the finish line. He used Junior as an excuse to skip practice.

“He’s sick,” Joey told his coaches. “My brother’s sick.”

At Junior’s funeral, and throughout the years that followed, guilt threatened to swallow Joey whole. His chest tightened, his breathing came fast and shallow. When he could no longer stare at Junior’s grave, Joey looked up at a nearby tree. A red-tailed hawk rested among its branches, staring back at him.

Joey watched the hawk for a few moments. Then it flew away.

Three years after burying his brother, Joey lay broken on a mattress in a psych ward.

He was just 18, halfway through his freshman year of a nursing program at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville. The hours Joey had spent in the hospital with Junior left a scar, and he wanted to help people in similar situations. Getting away from home, if only a few miles up the road, might’ve offered an escape. But freshman year morphed into one of the worst periods of Joey’s life. He didn’t know how to process what had happened with his family, and he’d begun to question his upbringing in the Nazarene Church. Above all, he knew he was gay, and he had no idea how to tell his mom, who’d watched Joey’s older brother die of AIDS.

Joey couldn’t picture a solution. At his lowest point, he tried to take his own life. He ended up in that psych ward for a week. Once Joey was allowed to see visitors, Brenda showed up at his bedside along with John, Joey’s baby brother.

“Why’d you do it?” Brenda asked Joey.

He paused for a second. This, he knew, was the moment.

“Because I’m gay,” he said. “And I can’t deal with this.”

John started to cry. Joey felt awful. John was 8 years old, and he was just happy to see his big brother alive.

Brenda didn’t hesitate. “I don’t care,” she told Joey. Her words were alchemy. The weight he carried began to lighten.

Around the same time, a friend from Clarksville brought Joey to Nashville to visit a gay bar called The Connection, which operated at Fifth and Demonbreun. Joey felt queasy when he walked in. He couldn’t grasp what he was seeing — drag queens, the thrum beneath the party, flashing lights, waves of uninhibited humanity. He saw men kissing each other, in public, without fear. He was shocked. He was euphoric. Two-thirty in the morning arrived, and he found himself still dancing, hooked on a feeling.

Before long, Joey was the one moshing on the raised platform, shirtless, sweaty, having the time of his life. The queasy feeling hadn’t entirely vanished. On several nights out, he saw Junior’s ex at The Connection. But Joey felt whole when he was in the bar. One night, he walked over to ask a bartender for a glass of water. Only, he didn’t really ask — it was more of a demand. He stated, in a flat tone and without preamble, “Water.”

Todd Roman grabbed Joey Brown by the back of his neck. Todd was manager at The Connection, and had been named Best Bartender in the Scene’s Best of Nashville issue. He prided himself on his handshake — he grew up on a farm, so his grip wasn’t gentle. He pulled Joey toward his face, until they were nose to nose.

“You should always say please and thank you,” Todd whispered.

Joey was shocked, and also a little chastened. He apologized. From then on, whenever Joey came to the bar, he and Todd always talked. A friendship began, and briefly, a relationship. Before long, Joey got a job waiting tables at The Connection. He began to realize that he didn’t love nursing, that what he felt out at the bar was a feeling worth chasing.

Over time, Joey and Todd both grew frustrated with The Connection’s ownership, who they didn’t think paid their employees well. If Joey and Todd wanted any sort of future, something needed to change. The breaking point arrived on a holiday, when ownership decided to raise the door cover. Todd argued that they should at least hire some entertainers, since the customers would expect something special if they paid extra.

“Fuck ’em,” the owner said. “Where else are they gonna go?”

Todd despised this attitude, and he said so.

“If you think you can do it better,” the owner replied, “then go do it. Until then, you’ll do what I say.”

Todd Roman and Joey Brown

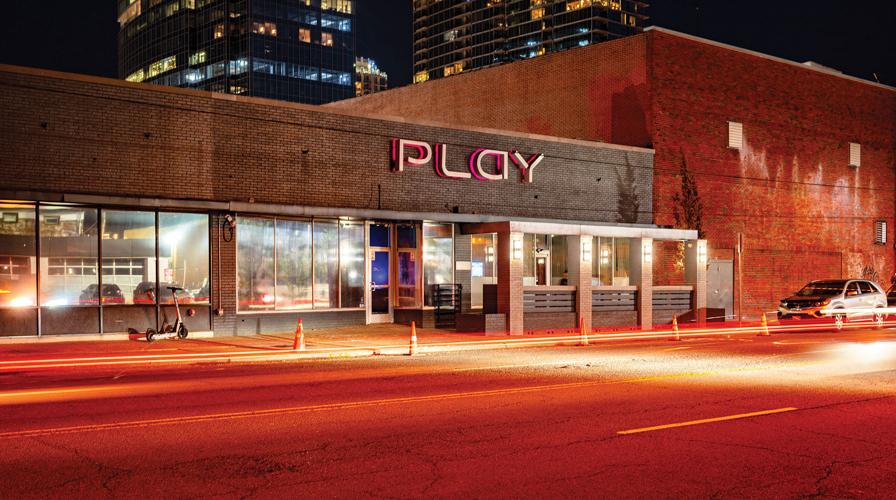

The night before they opened Play, their very own club on Church Street, Joey and Todd lay on their shiny, spotless dance floor and stared up at the ceiling. They’d just finished the sound system, so they turned on the dance lights and the music. It was just the two of them.

After arguing with The Connection’s owners, Todd realized that he could, in fact, do it better. He talked to Joey about opening their own club, knowing that Joey — who’d grown up buying and reselling candy, watching his parents run McCoy’s Market — would make a great entrepreneur. Their first step was leaving The Connection. Through a mutual friend, Todd met David Taylor and Keith Blaydes, who’d just opened a bar called Tribe on Church Street. Todd tended bar for them and helped them launch the business. They knew he wanted to start his own bar, and that eventuality was part of their initial agreement. Soon after, Joey left The Connection and joined Tribe.

Meanwhile, Joey and Todd saved every penny they could. Todd sold his Acura NSX, but they still couldn’t quite get over the finish line. In the end, Todd went to his father, who was supportive, and took out a $100,000 loan.

On opening night in 2004, Play was packed. Joey and Todd watched it all from the elevated DJ booth, working the lights, looking down at smiling faces. They’d managed to bottle that first-time feeling — the queasiness and euphoria, the exhilaration cut with a hint of fear, that anticipation that makes you shiver. Show up any night, two decades later, and you’ll feel it still.

A few months after Play opened, The Connection went out of business. By the time Joey turned 28, Todd says, he was a millionaire.

“I still think about my brother,” he says, years later, sitting in his club’s lounge.

“I think he’d be really proud.”

One night at a party, Joey’s friend Lana told him she wanted to run a marathon.

“Yeah,” he told Lana. “I’d like to do one, too.”

As they began training, Lana thrived while Joey struggled. He hadn’t run since he was a freshman skipping cross-country practice, grieving Junior.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” Lana asked him.

“I’m going to run a marathon,” Joey assured her. For his brother’s sake, he wouldn’t quit.

Two months out, during a 16-mile run, Lana got injured. She wouldn’t be able to race. Joey’s confidence began to trickle away. Lana had been the one to push him, and now, he’d have to finish training on his own. One day, on Percy Warner’s 11-mile paved loop, weaving through trees and fighting up hills, Joey could go no further. He was so mad at himself that he started to cry.

I’m gonna quit, he realized. I’m just gonna quit.

Twenty feet from where he’d stopped, a red-tailed hawk swooped down and landed on a tree branch. For a moment, the world went silent. Time froze. No one else was around. Just Joey and Junior.

On the day of the Country Music Marathon, as he raced across Nashville, Joey scanned the skies. It felt written, preordained. He was so ready for the moment, so primed for that huge emotional payoff, but it never arrived. When he crossed the finish line, he knew he’d accomplished something big. And yet, in spite of what he’d just done, he couldn’t help but feel let down.

When he got back to the house he and Todd shared, Todd and Lana waited outside. “Why don’t you come upstairs?” they asked him. “We got something for you.”

Joey climbed the stairs and opened the door to his bedroom.

There, lying on his bed, was a statue.

It looked just like a red-tailed hawk.

Plus we chat with hometown queen Aura Mayari and delve into the history of Play