On April 17, 1975, the victors of the Cambodian Civil War occupied Phnom Penh, the country’s capital, and marched its 2 million inhabitants into the countryside. While Saigon fell in neighboring Vietnam, Khmer Rouge revolutionaries cut off Cambodia from the outside world and began to implement their fanatical vision: resetting their civilization’s history to “Year Zero” and transforming a modern nation into a brutal agricultural slave-labor collective. They abandoned the cities, schools, hospitals, temples and businesses; killed a generation of leaders, monks and professionals; and forced the entire population into camps to work the land, to be starved and terrorized, in an attempt to make them forget who they had been.

By the time Vietnamese troops ousted Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge in 1979, an estimated 2 million Cambodians had died by execution, hunger, torture or disease. The country was in ruins. Hundreds of thousands of sick and starved Cambodians braved battle zones, banditry and minefields to reach the U.N. refugee agency’s overflowing camps in Thailand. More than 150,000 Cambodian refugees, many with the help of the United States Catholic Conference (USCC), were resettled in the United States, with the largest diasporas gathering in Long Beach, Calif., and Lowell, Mass.

Nashville’s Cambodian community, by comparison, is relatively small. A 1989 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report estimated that beginning in 1978, around 100 families — or 500 people — had settled here. Many lived on Archer Street in Edgehill and along Shelby Avenue in East Nashville. They found work in factories, an African violet greenhouse and the Gaylord Opryland Resort. They resisted their own erasure by living, and by refusing to forget who they had been.

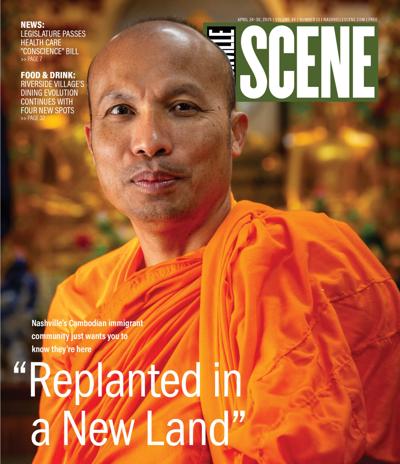

On the 50th anniversary of “Year Zero,” the Scene checked in with our city’s Cambodian community to find out how they’ve built new lives as Americans, Southerners and Nashvillians. They recalled coming here with nothing, and the support they received — from USCC, ESL teachers, YMCA counselors, public assistance and the Belmont Baptist Church. They told us with pride about converting a modest house off Dickerson Pike into a Buddhist temple and community anchor. They discussed businesses they’ve launched, children they’ve sent to school, homes they’ve saved up for. They also spoke of genocide’s ghosts: shattered aspirations and the buried fear and pain that emerge as anxiety, haunted silences, anger — and occasionally, mental illness or violence. And they defined the ingredients of their extraordinary resilience: hard work and gratitude; commitment to family, faith and their close-knit community; and awestruck thankfulness for the miracle of being alive at all.

Here are a few stories of who the Cambodian Nashvillians were, who they are now, and who they’re still becoming.

The temple’s annual community memorial blessing took place March 23

The longtime Nashvillian wants to celebrate Cambodian joy

The Cambodian monk teaches compassion

Sok sees Nashville’s Khmer diaspora as a success story of transcending hardship

The pair found each other decades after chaos forced them to become refugees