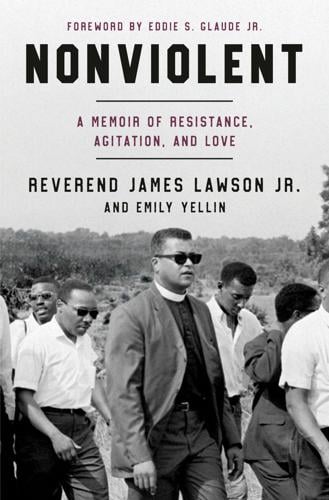

In his last and greatest sermon, on April 3, 1968, at Mason Temple in Memphis, Martin Luther King Jr. applauded his fellow minister James Lawson. “He’s been to jail for struggling,” said King. “He’s been kicked out of Vanderbilt University for this struggle. But he’s still going on, fighting for the rights of his people.” In Nonviolent: A Memoir of Resistance, Agitation, and Love, Lawson recounts a life fighting for civil rights. He shaped many of the movement’s key struggles, from Little Rock to Nashville to Birmingham to Memphis.

Before he died in 2024, Lawson collaborated on the book with Emily Yellin, a longtime contributor to The New York Times and other national publications. Yellin is also the author of books including Our Mothers’ War: American Women at Home and on the Front During World War II and the producer of Striking Voices, a 10-part video series about the 1968 Memphis sanitation strike. Yellin answered questions via email.

You called the Rev. Lawson one day in 2020 and asked about working together on his memoir. How did you know him, and why did you want to tell his story?

I have known Rev. Lawson since I was 5 years old, when his oldest son John and I were in elementary school together. My parents and he and Mrs. Lawson became friends while working together in the movement in Memphis. At various times in my life since, our paths have crossed.

When the pandemic came, I thought working with him on his memoir was something we could do, even though we were stuck at home for a year. His family had wanted him to do it for decades. And our family connection meant we had a trust that served us well. He said our working together was providential. I said it was a secular parable about being nice to your friends’ kids and your kid’s friends, because you never know which one might help you write your memoir one day.

The ethic of nonviolence defined Lawson’s approach to politics and society. How did he come to adopt this philosophy?

He found nonviolence first through his mother’s wisdom and then through studying the teachings of Jesus and Gandhi. It evolved during his time in federal prison for resisting the Korean War draft, his time in India and Africa in the mid-1950s, and his early work in the South with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a group committed to nonviolent social change.

How would you describe Lawson’s role in the civil rights movement over the course of the 1960s? He was somehow both a significant, controversial public figure and a quiet, behind-the-scenes force.

Dr. King said Rev. Lawson was the leading strategist and teacher of nonviolent direct action in the world. And John Lewis called him the architect of the nonviolent movement in America. The behind-the-scenes part was by design. He and Dr. King agreed that he would be the one to operate under the radar in many of the campaigns he helped lead. That way, in Birmingham for instance, when everyone else was in jail, he could still strategize and organize on the outside to move the cause forward. In Nashville, he recruited and trained college students like John Lewis, Bernard Lafayette and Diane Nash to join in a campaign to end segregation in the city. But he was very adamant that the students, not him, would be the ones out front at press conferences and during demonstrations.

The civil rights leader died June 9 at age 95

You devote one of the four major sections in Nonviolent to Memphis in 1968, a period defined by the sanitation strike and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Witnessed through the eyes of Lawson, how did this turbulent moment look?

Just about everything ever written about 1968 in Memphis has been written by white, male historians. Much of it is very good. But we saw the need to dig deep into his account, partly because it would be the first major work written in first person by a Black person directly involved in that moment. It felt vital to get his perspective into the historical record. Also, it was such an amazing story of nonviolent resistance overcoming what Rev. Lawson came to call “plantation capitalism.”

Lawson writes of Donald Trump: “He has an emptiness — a vast hole in his soul.” How did Lawson interpret the politics of our time?

He also said that publicly about Tennessee’s governor, Bill Lee, when Lee enacted some of Trump’s health care and economic policies that hurt vulnerable people in the state. Rev. Lawson said the health of a nation, a state or a city should be measured by things like its infant mortality rate, its rate of people living in poverty, and the ability of all its citizens to make a living wage.

To read an uncut version of this interview — and more local book coverage — please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.