Justin Townes Earle had a thing he called “the myth” — the name he gave to the pervasive, destructive idea that all good artists have to suffer. “I believed the myth for a long time,” he once said. “I believed that I had to destroy myself to make great art.”

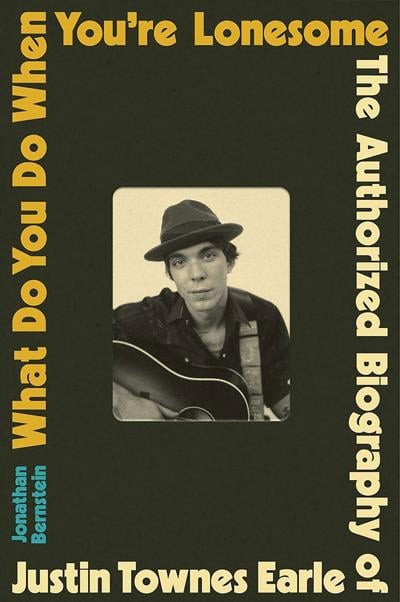

“The myth” is introduced early in What Do You Do When You’re Lonesome, the new authorized biography of the late, great roots musician by journalist and Rolling Stone senior research editor Jonathan Bernstein, out Jan. 13 via Da Capo Press. It recurs throughout: Justin wielded “the myth” as a persona, a self-aware story of redemption and recovery that played into his work. But Bernstein writes that he also “bore intimate witness to its curse.” It’s a fitting framework from which to consider an artist who wrestled with his relationship to addiction — as well as his own mythology, and that of his turbulent relationship with his father, fellow songwriter Steve Earle.

The elder Earle, who was often absent during his son’s childhood, was a frequent subject in Justin’s songwriting. The 2012 album Nothing’s Gonna Change the Way You Feel About Me Now opens with the line “Hear my father on the radio.” “Mama’s Eyes,” an addict’s confessional from 2009’s Midnight at the Movies, repeats the refrain “I am my father’s son” but reframes it for “I have my mama’s eyes.” Steve, for his own part, sang from afar to Justin in “Little Rock ’n’ Roller” from his 1986 breakthrough album Guitar Town — and after Justin’s fatal overdose at age 38, in “Last Words” from his 2021 tribute J.T. Behind the stories they told about each other, there was a dynamic as intertwined as it was complicated — a push and pull not just between father and son, but between artist and artist, in conversation and at odds.

What Do You Do When You’re Lonesome deftly considers the nuances of that relationship, dusting off the lore around it and eschewing easy descriptions to get to its heart. Bernstein does the same revelatory work with other legends whose lives intersected with Justin’s, painting a vivid portrait of an artist who until now has been shrouded in other people’s stories. There’s the mythology of Nashville, which changed drastically over the course of Justin’s lifetime, and where he started his career with the band the Swindlers — it’s also where he established fleeting friendships with Jason Isbell and David Berman. There’s the gospel of his namesake, Townes Van Zandt, which his father was instrumental in spreading, and the lives of musicians like Jimmie Cox who inspired Justin’s work.

And of course, there’s the cautionary tale of the music industry, which caught up with Justin’s lifelong fascination with folk and the blues during the 2000s’ “stomp-clap” movement and the rise of Americana, but left him empty. Justin’s work was buoyed by an online landscape of indie bloggers and CD sales, but both dried up with the rise of streaming and the decline of music media more broadly. By the end of his life, he was nearly constantly on tour. “Music has an ugly side,” he once wrote in his journal, “and it is the business.”

All addicts know the bottom exists, and they know someday they’ll slam against it. They just can’t predict when, where and how—or with how muc…

Bernstein writes with empathy and resolve, illuminating each mythos with intimate entries like these, as well as interviews, unpublished lyrics, unreleased recordings and careful research — including some from the Scene’s own pages. Thorny topics like Justin’s mental health and sobriety and his lineage in the history of white musicians taking inspiration from Black music are explored gently and with grace. Bernstein considers Justin’s place in Nashville’s history through the development of Belmont-Hillsboro, where he grew up alongside the children of Vanderbilt professors and songwriters, and of Lower Broadway, which Bernstein explains became a “country-music amusement park” around the time Justin moved back to the city in the 2010s. “What Nashville means to me isn’t here anymore,” he told the magazine Songwriting at the time. “It’s buried under a bunch of crap and trampled under the feet of a whole new population that has moved here from L.A.”

And isn’t that, after all, the project of biography after death: to bring to light someone who isn’t here anymore, and show us a new way to see them? With What Do You Do When You’re Lonesome, Bernstein doesn’t just reflect on Justin Townes Earle’s legacy — he excavates it, and asks us to look again.