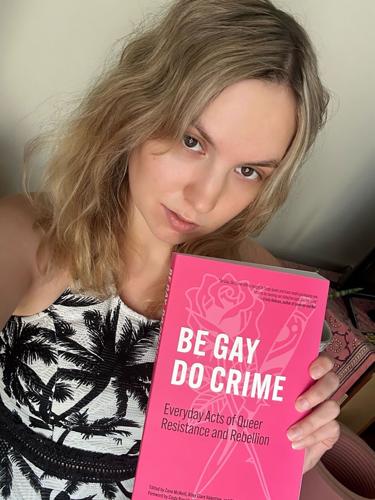

Zane McNeill

The LGBTQ community has long struggled for respect, acceptance and safety in the face of a hostile society, but the struggle has been marked by courageous — even joyful — resistance and resilience. Be Gay, Do Crime surveys the history of that resistance through a daily catalog of notable events.

In this carefully annotated volume, editors Zane McNeill, Riley Clare Valentine and Blu Buchanan take us from Jan. 1 (the date in 1962 when Illinois became the first state to repeal its “crimes against nature” statute) to Dec. 31 (when, in 1918, openly lesbian labor activist Marie Equi was convicted of sedition for criticizing corporate profiteering from the U.S. war effort).

McNeill, whose previous books include Y’all Means All and Deviant Hollers, answered questions about Be Gay, Do Crime by email.

This book required a massive data-gathering effort. What did you learn that surprised you?

I was surprised by how much of gay history is difficult to organize and verify by specific dates. This makes sense though, because “gay history,” like much of history, is often represented by the wealthy and elite — those most likely to make it into the archive and have their history written down. We tried our best to include as much counter and radical queer history as possible, while still ensuring the information could be verified.

Which of the book’s entries do you find especially fascinating or empowering?

I hadn’t realized how much of the labor victories we usually credit to Franklin D. Roosevelt were in fact shaped by Eleanor Roosevelt and her circle of lesbian friends. This is just one example of many in the book that show how queer history has been eclipsed and, in many ways, rewritten from a cisgender and patriarchal perspective. By recovering and reexamining these histories, we gain a profoundly different understanding of the past — as well as a better understanding of our current political moment.

You urge readers not to read the book alone but to share it in community with others. Do you have particular suggestions for what that might look like?

There is an increasing risk in being openly queer, reading queer books and creating queer spaces. But that is why it is so important to do just that. Learning from our history in community with others terrifies the far right. Fascists get power from making us small and scared — too scared to read, to dream, to live. But they are the ones who are so scared of us and our power and our joy. Refusing to be silent and invisible greatly weakens them. That is why I ask y’all to read this book together in book clubs, bring it to your local outdoor library, and leave it at queer coffeeshops and LGBTQ centers.

The LGBTQ community has long been targeted by the political right, but you also point to tensions or conflicts between different segments of the community. How can Be Gay, Do Crime help people better understand and navigate those conflicts?

We try to highlight the many different visions of what liberation has meant. For example, the Mattachine Society began in the 1950s with a radical critique of mainstream society, but soon shifted toward a politics of respectability and acceptance within dominant culture. Frustration with these assimilationist tactics helped give rise to more radical groups such as the Gay Liberation Front and the Queens Liberation Front, which demanded broader structural change and greater inclusion of drag and trans communities.

These tensions over tactics and goals — particularly over who is included in a group’s vision of liberation and who is left behind — have continued to surface within LGBTQ spaces. Queer activists have at times directly challenged other LGBTQ organizations, as seen with the Black Pride 4 at Columbus Pride in 2017, No Justice No Pride at D.C. Pride in 2017, and Black Lives Matter—Toronto organizers who halted Toronto Pride in 2016.

We sought to include as many of these groups, protests and conflicts as possible so that readers can learn from the past — both from tactics that proved successful and from those that fell short.

The stakes for LGBTQ people have always been high and are likely to remain so in the foreseeable future. How do folks hang onto joy?

Joy itself is an act of resistance, demonstrating the resilience and ungovernability of queer and trans people despite state surveillance, criminalization and pathologization. Many entries in this book document the state’s attempts to crush queer and trans joy.

Police raids of William Dorsey Swann’s birthday drag ball in 1888, Eve’s Hangout in 1926, the Tay-Bush Inn in 1961, The Patch Bar in 1968, The Snake Pit in 1970, “Operation Soap” in 1981, the Glad Day Bookshop in 1982, Club Toronto’s Pussy Palace in 2000, and raids on gay leather bars in Seattle in 2024 show the state has long been threatened by queer and trans joy.

Yet despite such targeting, queer and trans people continue to carve out community and resist police violence. They protested each of these raids and the arrests that followed, showing up to confront the state in defense of their communities. This act of standing together is an expression of love. Every moment of protest documented in this book is also a moment of joy — because queer and trans people organizing, engaging in community defense, and fighting for liberation embody joy itself.

To read an uncut version of this interview — and more local book coverage — please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.