Acclaimed author, podcast empire cornerstone, perceptive critic and Vanderbilt alumnus Alonso Duralde has been a fixture in cinema discourse for several decades now. As both a media personality (that’s him on your Valley of the Dolls DVD and Boom! Blu-ray and periodically on TCM) and a film critic, he’s helped queer cinema become a topic easily approachable from the mainstream, which doesn’t even get into his status as one of the foremost scholars and advocates for Christmas cinema. (He has authored several books on the subject, as well as being part of the podcast Deck the Hallmark.)

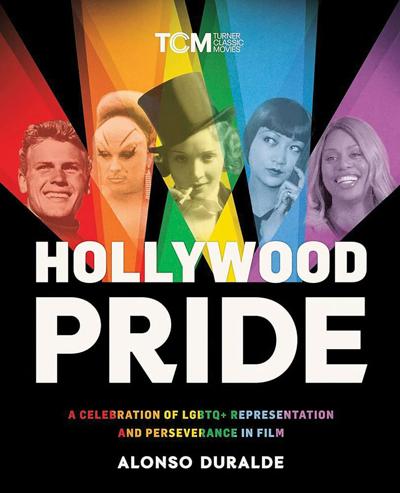

He recently released his book Hollywood Pride: A Celebration of LGBTQ+ Representation and Perseverance in Film (Running Press), and he was an absolute delight to talk with in advance of his upcoming appearance at the Belcourt.

How did the idea for, and structure of, this book come together?

Running Press brought it to me, they sort of pitched me the idea. This is of a piece with a couple of other books they’ve recently published — Donald Bogle’s Hollywood Black and Luis Reyes’ Viva Hollywood. So those books gave me a template as to how to incorporate the films themselves and the characters, but also the artists in a chronological framework. There was a lot to get to, so it had to be a lot of short essays and notes, because to encapsulate 130 years of cinema history into 95,000 words meant the reader was going to get a taste of everything along the way, but there just wouldn’t be enough real estate to go too deeply on any one topic.

It had to be a Whitman’s Sampler. Part of the journey of Hollywood Pride was encountering all these interesting facets that I’d never encountered before. I’ve got my theory background, I took cinema studies classes, and I know my sissy elders, but I’d never heard of J. Warren Kerrigan, “The Great Unwed,” before.

I absolutely have to tip my hat to William Mann’s Behind the Screen; he really found a lot of these folks and talked to so many of the survivors of that era who were still alive when he was writing the book, so he pointed me in a lot of the right directions.

What was the big discovery for you in the research phase?

As I was putting this book together, Tre’Vell Anderson’s book We See Each Other was coming out, and that was the first time I ever heard about Angela Morley, and I was shocked that I had never come across her before. She was the first openly trans person to be nominated for an Oscar — she worked as an arranger and a conductor for not just Lerner and Loewe and the Sherman Brothers, which she got her Oscar nominations for, but also John Williams. When you think of his major iconic scores — Star Wars, Superman, E.T. — she is part of his team, putting those scores together in a nuts-and-bolts kind of way. But she also won Emmys for doing music for shows of great interest to the queer community like Wonder Woman and Dynasty. So how I had never encountered her name before, heaven only knows. But I’m happy I was able to give her a bit of a spotlight in this book.

Similarly, Thomas Gomez was someone I’d never heard of before, despite having seen a lot of his work.

And I’m Spanish American — I should know this guy. He was the first Spanish American Oscar nominee. It’s a lot of history, and as the medium gets older, it becomes harder and harder to have a full grasp on things as one once might have. I remember reading an article about Peter Bogdanovich in the mid-’70s where they could actually quantify the number of Hollywood studio films that existed and the percentage of them that he had seen. And then a few decades later [there’s] this explosion of indie and international cinema, where we’re getting access to more titles than we ever have before. I think about my niece, who studied screenwriting at Emerson and is now working on scripts herself, and it all feels like too much. It’s like being someone who studies literature immediately after the invention of the printing press versus 200 or 300 years later. The scope of it all exceeds the ability of any one person to wrap their arms around.

There is no magical Bogdanovich ascot that can encompass the whole of Queer Cinema History. I very much appreciated the delicate but unapologetic approach you, and all queer historians, have to those moments when we have to dip a toe into the gossip mill.

This is something that queer historians in every realm have to deal with, whether you’re talking about history or literature or whatever. Henry James’ family kept his letters suppressed for a very long time. It’s only recently that we know about the correspondence between Bram Stoker and Walt Whitman.

And this is a suppression that exists throughout all the academic disciplines. I don’t know if you saw the documentary Queer Planet that just premiered on Peacock recently, but it’s a study of same-sex activity and transness as practiced in the animal kingdom. For a very long time, if you were a scientist or a naturalist and you were trying to explain that there were same-sex pairings among penguins or bighorn rams, that would be suppressed in official channels. You could lose your grants, or not be published, or just not taken seriously in the scientific community, because there was this effort to keep down the idea that queerness occurs in and is part of the natural world. So there are constantly these forces of censorship at play, and in this case you have the very real example of people living their lives in a society where they could lose their jobs or they could go to jail if their sexuality was public knowledge. So trying to put that together decades later, you sometimes do have to rely on word of mouth and hearsay for those examples where you don’t have letters or a diary or a late-in-life interview; this just isn’t the sort of information you can glean from birth certificates or land records.

Through the course of your research, who’s your favorite gay villain?

I’ll give you a recency bias because I just rewatched All About Eve, and Addison DeWitt is … [Laughs] But I would love to see him go toe to toe with Waldo Lydecker from Laura. That period of gay snake I find very fascinating.

That’s the steel-cage match where all of a sudden Mrs. Danvers swoops in from the side with a folding chair. Dare we dream of a Queer Cinema Mortal Kombat?

Bon mot at 10 paces.

One of the highest compliments I can pay this book is that on my library shelf, it’s right next to Raymond Murray’s Images in the Dark. For the longest time, and in a pre-internet context, it was the most comprehensive and entertaining guide out there, and I feel like what you’ve accomplished here explores and works within that milieu very well.

This book stands on the shoulders of William Mann and Vito Russo and B. Ruby Rich’s work, and my hope is that one day, for some future author, this is part of the foundation of books on this topic for the next step in this field of thought.

So what specifically made you choose The Last of Sheila as the film you wanted to present for Nashville audiences?

First of all, it’s fun. It’s funny, it’s a very bitchy comedy. I love Stephen Sondheim, and I can’t believe this is the only screenplay he ever wrote with his longtime pal Anthony Perkins. You have the production code period in Hollywood, the Hays Code, where officially queer characters do not exist, even though they’re still snuck in between the lines. And then that period ends in the ’60s, and you get a lot of not-great queer representation, because you’ve still got mostly white straight cis men making the movies, and you get a lot of villains and punchlines. But this movie takes the new freedom of post-code Hollywood and weaves queerness into an overall narrative, and because it’s set among Hollywood types, of course there’s going to be queerness there. You’ve got Herbert Ross directing, who has his own history off screen — ask Arthur Laurents. And you have this web of bitchiness and literal homicide and gossip and backstabbing — it’s tremendously entertaining. I love that Rian Johnson is always citing it as one of his major influences for the Knives Out films, and I’m always stunned when it comes up in conversations how many people have never heard of it. It’s always a delightful surprise.

Can you imagine what would have happened if Sondheim and Perkins had been able to make Clue work?

That is a timeline I would really love to see.