Once a month, reporter and resident historian J.R. Lind will pick an area in the city to examine while accompanied by a photographer. With his column Walk a Mile, he’ll walk a one-mile stretch of that area, exploring the neighborhood’s history and character, its developments, its current homes and businesses, and what makes it a unique part of Nashville. If you have a suggestion for a future Walk a Mile, email editor@nashvillescene.com.

The Route: From Columbine Park, south on Columbine Place, then right on Heather Place, then right on Bransford Avenue. Turn into Woodlawn Memorial Gardens at Bransford’s intersection with Melrose Avenue and walk about 800 feet to the cabins.

Cranes: 0

Abandoned Scooters: 0

Even on a muggy, overcast June morning when the air hangs like a thicket of cobwebs before the sun has burned off the humidity that settles on warm nights in Middle Tennessee, Berry Hill’s Columbine Park is a pleasant splash of green. Set between two one-way stretches of an eponymous road, the park is open but for a few benches and some strong-looking ancient trees. It’s a park for the sake of having a park, which is a fine reason to have a park. On its northern end, Columbine is overlooked by the House of Blues Studios, owned by Universal Music Group since 2019. It’s a multi-building complex that includes Studio D, which was moved whole-cloth from Memphis about a decade back. Murals along the walls and fences nearby feature faces of the legion of artists of all genres (from Ralph Stanley to Lady Gaga) who have laid down tracks in the studio.

Moving south on Columbine Place, the character of Berry Hill becomes apparent. Homes, restaurants, offices and businesses are neighbors in the quaint World War II houses, unseparated by the vagaries of a zoning code that would keep them apart. The mishmash would horrify the midcentury ultra-rationalist planners who would see all cities become barely connected clutches of commerce and entertainment and home life, none infringing on the other. But in Berry Hill, planning seems to have been conducted simply by happenstance.

Berry Hill, of course, handles its own planning and zoning, among other municipal duties, having survived 1965’s consolidation of Nashville and Davidson County (along with Belle Meade, Forest Hills, Oak Hill, Goodlettsville, a smattering of Ridgetop and the now-evaporated Lakewood). These areas are usually called “satellite cities,” though the Metro Charter simply designates them “smaller cities” and allowed those existing prior to consolidation to continue doing so, unless — as Lakewood did — the residents choose to surrender the charter. Thus freed from those bounds, Berry Hill chugs along, a quirky little pocket where someone’s house is next to the Nashville Jam Company, itself next to a facility offering high colonics and reflexology.

Pseudoscientific health seems to be a bit of a cottage industry in Berry Hill, with a statistically significant number of herbalists and crystal purveyors alongside an alarming number of dentists (and the home of the surely-more-powerful-than-we-know lobbying group, the Tennessee Association of Optometric Physicians).

Sidewalks are scarce, but so is automobile traffic, on Columbine Place as it curves southwest into Heather Place, which runs along the backside of two of Berry Hill’s most visible and well-known businesses: Baja Burrito and Sam & Zoe’s. The latter — with its multilingual sign advising wrong-way drivers to stop lest they cause a slow-speed head-on collision in the modest drive-thru coffee line — is the destination of a handful of joggers seeking their morning jolt.

Turning north on Bransford — more or less the main drag in Berry Hill proper, with Thompson Lane a more well-traveled road but lacking the character of its perpendicular sister — more beloved small and local restaurants are readying for the day. The bread for the banh mi and the broth for the pho are no doubt in the works at Vui’s Kitchen, the lunch specials are being prepped at The Yellow Porch and Sunflower Cafe, and folks are grabbing a quick breakfast at Cafe Monell’s.

The restaurants match the wood-siding/clapboard cottage look of the neighborhood. While consistent zoning isn’t much of a concern in Berry Hill, aesthetic consistency surely is. An exception is at the prosthodontist’s office (sadly, a prosthodontist is not a dinosaur — they are dentists specializing in prosthetic devices) just south of Monell’s: It’s a vaguely Spanish Colonial building by way of fast-service restaurant at EPCOT. A few doors north is what is probably the only plaid building in all of Davidson County. This stretch of Bransford is a smorgasbord of niche businesses: tattoo artists next to specialty dentists next to a bead shop next to a scuba store. A video-production house shares a block with The Pfunky Griddle, from whence the seductive scent of bacon is wafting in the heavy June air, as well as a vaguely named consulting shop.

At Bransford’s intersection with Iris Drive is a windowless abandoned building that looks vaguely like an old roadhouse. A secret government facility? Probably not. It was most recently an art gallery. At various times in the 1960s and 1980s, the property was owned by Woodlawn Memorial Park, the cemetery it neighbors, which used it as a source of revenue for the perpetual care fund.

One of the city’s largest burial grounds, Woodlawn is the final home of a number of music figures and regular Nashvillians. It dominates the southeast quadrant of Berry Hill, extending beyond Thompson Lane and thus stretching into Nashville proper, or what demographers and statisticians call “Nashville-Davidson (balance).” Like cemeteries should be, it is quiet and well-maintained with a relaxing park-like atmosphere and a grid of paved roads, essential because the sidewalk narrows and then disappears at Bransford and Melrose.

It’s little more than a week since Memorial Day, thus many of the headstones are still decorated in the patriotic colors, the wind whistling through the bunting and blooms being the only sound other than the rumble of traffic on Interstate 65. But beyond the remains and the memories of Nashvillians since passed and their families, Woodlawn also holds a curious secret.

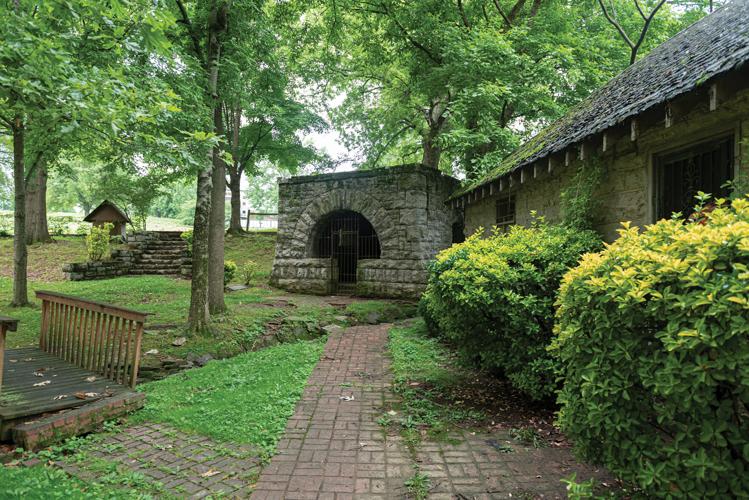

Close to the midpoint of its northern edge, facing a bland industrial park, is what looks like a small village of historic homes, a sort of outdoor museum of early Nashville life with pleasant ponds and bubbling streams and a rowdy flock of Muscovy ducks. The crimson bulbs on their heads contrast with the black and white of their feathers as they swim around squawking at a school of koi. The main house in this little campus is Melrose, once the home of Gov. Aaron Brown. Brown, one of many one-term governors in the 19th century, succeeded the delightfully named James Chamberlain “Lean Jimmy” Jones in the governor’s mansion, and in his 64 years he always circled on the fringe of the powerful. Brown served in the U.S. House and the state Senate, was future President James K. Polk’s law partner and was postmaster general under President James Buchanan.

In the 1960s, the house was purchased by the Forehand family, who expanded it and modernized it — the still-extant window air conditioning units were not original to the home, nor was the stubborn artificial poinsettia that’s hung on the door for who knows how long. The Forehands, obviously interested in history, took the time to erect plaques explaining each of the buildings, though their particular interpretation thereof is certainly a product of their time. For example, a Confederate cannon (no longer present) is described as having participated in the valiant defense of the city against the Union attack in the “War Between the States.” (There’s a lot wrong with that description, not the least of which is that the defense of Nashville was more “completely ineffective” than “valiant.”)

One small building is described as “servants’ quarters,” as if a well-paid butler lived there and not someone enslaved by the Brown family. Its plaque tells the harrowing tale of a child, asleep in the cabin (it also served as the Browns’ nursery), who was nearly shot in the head by a bullet fired from a Union troop train. That seems unlikely given that the nearest railroad tracks then, as now, are more than a half-mile away and the range of a Civil War-era musket was about half that distance. There is a springhouse that provides the water for the ponds and stream; its regular and reliable flow led to a field hospital being set up in what is now the cemetery.

There is one building not original to the site: the Carper homestead, which was built in what is now Cane Ridge shortly after James Robertson et al. founded Nashville. It was broken down and moved piece by piece to Woodlawn in the late 1960s. Connecting this old piece of Nashville with what it has become is a red Solo cup that sits empty outside the front door, which is open, the heavy lock ripped off by ne’er-do-wells. Inside, a few family photographs sit on the mantle. Even more creepily: One of those faceless articulated-wooden-human-body drawing figures lies on the cabin floor.