Bobby Hebb was born in Nashville on July 26, 1938, and succumbed to lung cancer in the same city on Aug. 3, a very full 72 years later. The life he lived in the time between took in the depth and breadth of popular music as few others ever have.

Hebb played country music at the Grand Ole Opry and got songwriting advice from Hank Williams. He rocked out with Bo Diddley in Chicago and swung with Count Basie in New York City. He played jazz for the wife of Chiang Kai-shek in Hong Kong and warmed up crowds for The Beatles across America. Artists ranging from Frank Sinatra to Wilson Pickett recorded his best-known song, but none made it a bigger hit than he did. Bobby Hebb's was a life uniquely American, and indeed uniquely Nashvillian.

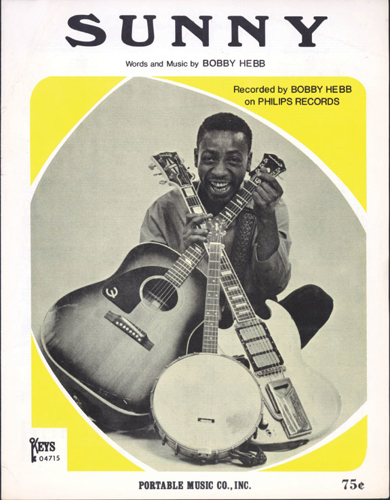

Hebb was onstage tapdancing by age 3, and he and his older brother Harold were soon veterans of the Nashville nightclub scene. He joined Roy Acuff's Smokey Mountain Boys in the early 1950s, only the third African American to grace the Opry stage. "It had nothing to do with an ethnic thing," he said. "Nashville has always been Nashville, and its music has always been its music. Every form of music." He later headed to Chicago, where he put in time at the venerated Chess Records recording studio before joining the Navy. There he played the trumpet with the U.S.S. Pine Island Pirates, demonstrating a talent for one of the many instruments in his arsenal (which also included guitar, piano, drums, banjo and spoons). He headed for New York City in 1961, where he briefly replaced Mickey "Guitar" Baker in the duo Mickey & Sylvia (promptly redubbed Bobby & Sylvia), but finally settled into a groove as a solo act.

In 1966, seasoned by his considerable geographic and musical travels, Hebb arrived at a moment that would define him in the public mind forever. The genesis of his trademark song, "Sunny," is murky. Many have traced its inspiration to a particularly tragic month for Hebb, November 1963: President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on one day, and Hebb's brother Harold was killed in a fight on the next. Hebb always downplayed the connection — but suffice to say that he'd been in a gloomy frame of mind when, under the influence of Tennessee sipping whiskey, he picked up his guitar and wrote the song. "I looked up and saw what looked like a purple sky," he later recalled. "I started writing because I'd never seen that before. And when I finished, I was sober."

"Sunny" came to Hebb like a stream of light through parting clouds. The lyric delivered a valentine of gratitude borne on the breeze of an airborne melody: "Sunny, thank you for the sunshine bouquet / Sunny, thank you for the love you brought my way." Hebb recorded the song in two takes during the last few minutes of a New York City recording session. Opening with a terse snare drum roll, Hebb's version is a model of restraint and taste. As a vocalist, he keeps a tight grip on his melody even as the band behind him gets swept up in the song's flood of optimism. Two minutes and 44 seconds later, the room is a little brighter. Hebb always maintained that the message of the song was a simple one. "Spread that type of news so that you can become a little more relaxed and not filled with chaos," he told the Scene in 2000. "Because chaos can become a killer."

"Sunny" was a nationwide smash, earning him a prominent spot on The Beatles' final tour. He followed it up with a soulful version of the country standard "A Satisfied Mind," and enjoyed a few minor hits over the next few years — but never again approached such heights as a solo star. He turned more to songwriting, winning a Grammy for the 1971 Lou Rawls hit "A Natural Man." Hebb earned the nickname "Song-a-Day Man," and claimed to have written more than 3,000 songs. But "Sunny" would remain his triumph, covered by hundreds of artists from around the world.

Hebb continued writing and touring for the rest of his life, and in 2005 released his first solo album in 35 years, That's All I Wanna Know. He was featured in the Country Music Hall of Fame's 2004 exhibit "Night Train to Nashville," which revived interest in Music City's long-ignored African-American R&B scene from which he first emerged. In his later years, Hebb moved back to Nashville. "When I'm on the plane and I look down, and I see how the Cumberland River bends and I see those hills," he said, "I know that I'm home." We can only thank him for the love he brought our way.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.