Cast your mind back with me to that long-ago time of 2020, when — on the 60th anniversary of the bombing of civil rights attorney and sitting city Councilmember Z. Alexander Looby’s home — I thought I would have the FBI file on the bombing shortly, after waiting two years for it. Three years after that — meaning five years after I requested it for the second time, which was a year after I’d received a letter from the FBI telling me, “Records that may have been responsive to your request were destroyed in September 1996” in response to me asking the first time in the spring of 2017, meaning six years in total from the first time I requested this file until now — I finally received the file.

The good news is that I can finally finish my book, Dynamite Nashville: Unmasking the FBI, the KKK, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control, which will be out in July. The bad news is that I didn’t have to rewrite anything in the book, but rather just slap an epilogue on it and call it good. If that isn’t just like the FBI — to lie about having destroyed a file that, when you see it, isn’t worth all the subterfuge. The funny thing is, if I’d gotten the file back when I asked for it, I probably would have taken it at face value, but now I know enough about the bombing that I can pretty easily spot the things that should be in the file and aren’t.

My general belief is that, in the 1950s and 1960s, to have a successful racist terror campaign, you needed three things: 1. Pissed-off local racists who were frustrated that the Ku Klux Klan was taking what they felt were only measured responses to local integration efforts. 2. Dynamite and someone who knew how to use it. 3. Local law enforcement that was either unwilling or unable to solve these crimes. Item one we had plenty of. Two we had because of our local racists’ ties to J.B. Stoner and Asa Carter. Three we had thanks to the FBI keeping information and witnesses from the Nashville police. And let me be clear: I’m not suggesting that the Nashville police in 1960 weren’t just as racist as police everywhere, but they were determined to solve the three bombings I’m looking at in my book, because the first bombing was of a white elementary school, and that was shocking and offensive to Nashville’s conscience.

OK, so, backstory on J.B. Stoner. He was a virulent racist from Chattanooga who lived in Atlanta. He and his buddies had been blowing up Black and Jewish homes and community buildings throughout the South. The FBI refused to step in and head up an investigation into him and his group, which made solving any of these bombings very difficult for local law enforcement, since Stoner often crossed state lines to make catching him difficult. In the spring of 1958, Southern cities headed up by Nashville held the Southern Conference on Bombings, where they shared information and swapped lists of known racist terrorists in their states. Circumstantial evidence suggests they identified Stoner as a lead suspect in these bombings. Crucially to this story, Eugene “Bull” Connor, the commissioner of public safety for Birmingham, Ala. (the guy who ordered firehoses and dogs be turned on children), was on Alabama’s list of known racist terrorists. (And honestly, fair.) Bull Connor was also one of Alabama’s delegates to the conference. Oops.

So he came home from the conference pissed and embarrassed and — in an effort to show that he too could fight the scourge of racist terrorism — set out to catch a racist terrorist. He just needed one who wasn’t his friend. Turns out J.B. Stoner wasn’t his friend.

Author Betsy Phillips’ Dynamite Nashville: The KKK, the FBI, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control is scheduled for release via Third Man Books…

So Connor assigned undercover cops to hire Stoner to bomb the church of the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. He agreed and offered to throw in the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King for $1,500 more. They declined at that time to the extra violence. The plan was that Connor’s men would schedule the bombing, and then police would arrest Stoner when he came to do it. Stoner, however, came a week early and planted a bomb right next to Shuttlesworth’s church. Only the fast thinking of a man who pitched the bomb into the street saved the building. So now, in essence, Bull Connor had just hired someone to bomb Fred Shuttlesworth’s church, and that person had done it.

Connor was in a pickle because he now owed Stoner for work done, but if he paid Stoner then he was completing a terrorist conspiracy that the FBI knew about, because Connor went and asked them for help getting out of this problem. When Stoner showed up again in Birmingham to collect his money, the undercover officer told Stoner that the people with the money didn’t believe that Stoner had committed the bombing, but that instead Black church members had bombed their own church for sympathy. The undercover officer could not give Stoner the money unless Stoner could prove to the moneymen that he had committed the bombing. Stoner, who had been raised by his police chief grandfather in Lookout Mountain, clearly found the situation sketchy and declined to prove himself.

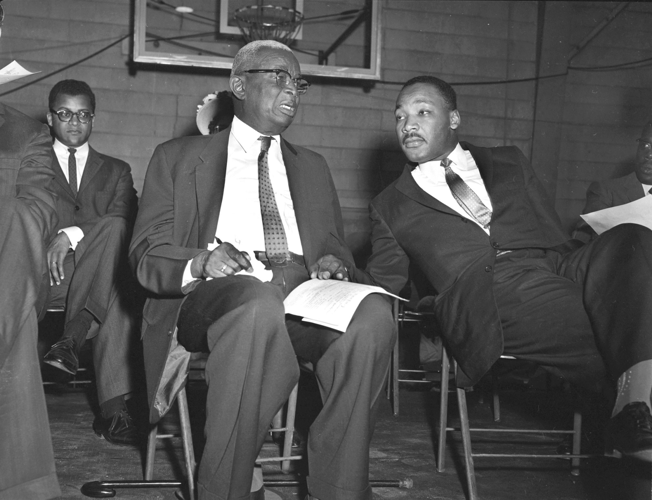

Z. Alexander Looby and Martin Luther King Jr.

But keep your eye on this: Stoner commits a bombing. Credit for that bombing, that everyone knows Stoner committed, goes to Black people.

This brings me to a bit in the Looby file I can’t decide about. After Looby’s house was bombed, the FBI started frantically trying to figure out where Stoner had been on the night before the bombing. (To be clear, lest I make the FBI seem more on-the-ball than it was, Stoner usually came into town before a bombing and left before it, so whether he was in Nashville at the time of the bombing isn’t as important as whether he’d been in Nashville the week before, and there’s no indication in the file the FBI asked that question.) Turns out he was in Louisville, Ky. One of the FBI’s confidential informants in Louisville reported back to the FBI.

On April 21, 1960, LS T-2 advised that on that date J.B. Stoner had remarked that the recent bombing of a Negro home in Nashville, Tennessee, had been done by the “[racial slur]s” themselves in order to gain sympathy and to have a reason for the march by the “[racial slur]s” on the City Hall at Nashville, Tennessee.

I genuinely don’t know what to make of this. If this very line of reasoning hadn’t been used against Stoner in Birmingham to get out of paying him, I wouldn’t think much of it — just Stoner being an asshole. But this very thing had been used to discredit him. And certainly at least some of the people in Louisville were Stoner’s closest compatriots. They would have known that this line had been used once before on a bombing Stoner was very much behind. So was this an in-joke? His way of taking credit for the bombing without saying so, since most of the people he was likely to say this to would have known of his past with this reasoning? Or was it just a jerk thing to say that wasn’t any deeper than a jerk being a jerk?

I don’t know, but I wonder.