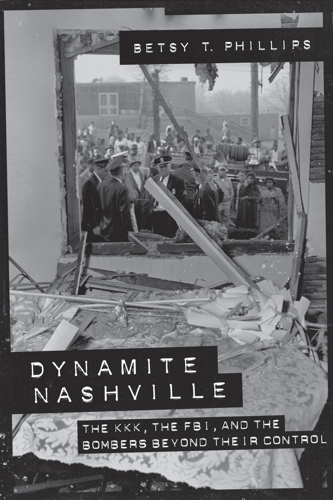

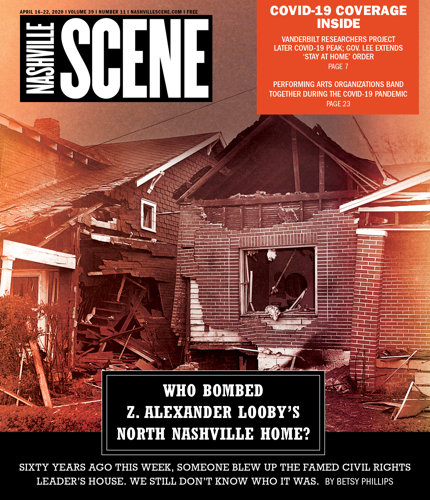

Author Betsy Phillips’ Dynamite Nashville: The KKK, the FBI, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control is scheduled for release via Third Man Books in early 2021. Below, read a primer on the unsolved 1960 bombing of Z. Alexander Looby’s home, and after that, find an excerpt from Dynamite Nashville.

Civil rights leader Z. Alexander Looby’s house after being bombed in April 1960

Sixty years ago, on April 19, 1960, someone dynamited the North Nashville house of NAACP leader, city council member and famed civil rights attorney Z. Alexander Looby. Looby and his wife Grafta were lucky to escape with their lives.

This assassination attempt on a sitting U.S. politician has never been solved.

A few hours after Looby’s house exploded, a long line of somber sit-in protesters — whom he’d been representing in court — and community supporters marched from the heart of North Nashville to the steps of the courthouse. There, movement leader Diane Nash asked Mayor Ben West, “Do you feel it is wrong to discriminate against a person solely on the basis of their race or color?” West admitted that he did.

It makes sense that we connect the Looby bombing to the sit-ins. Even Looby thought they were connected.

But likely, it was his work on school desegregation that first infuriated the people who tried to kill him. Looby — along with Avon Williams, Carl Cowan and Thurgood Marshall — represented the desegregationists in Clinton, Tenn., starting in 1950. When Clinton High School desegregated in 1956, that was Looby’s doing. When it blew up in 1958? Likely the doing of the people who would try to blow him up two years later.

In 1955, Looby, Williams and Marshall filed suit against the Nashville public schools on behalf of Alfred Kelley and his son Robert, who attended Pearl High School even though he could have walked to East High School. This led to the desegregation of some of Nashville’s first-grade classrooms in the fall of 1957, which led to the bombing of Hattie Cotton Elementary School on Sept. 10, 1957.

Even the bombing of the Jewish Community Center in Nashville on March 16, 1958, was tied to desegregation. When the bomber — likely racist activist J.B. Stoner — called The Tennessean, he said, “This is the Confederate Underground. We just blew up the center of the integrationists in Nashville. Now we are going after Judge Miller.” Judge William Miller was presiding over Kelley v. Board of Education, the desegregation case Looby was arguing.

This means the list of potential suspects in the Looby bombing has to include not just everyone who opposed the efforts of the sit-in protesters, but also everyone who opposed school integration. And on that list are some pretty heavy hitters.

John Kasper headed up the Tennessee White Citizens Council and the Seaboard White Citizens Council, and instigated the Clinton riot in the wake of school desegregation there. He was in Nashville most of the time — when he wasn’t in jail from 1957 through 1960. In one of his early segregationist protests, he declared that he had a noose for Looby.

Kasper had been coordinating at least since Clinton with Asa Carter, an Alabama Ku Klux Klan leader who had started his own offshoot of the Klan — because he felt the Birmingham Klan leaders were too soft on black people. Let me remind you: Birmingham’s nickname at the time was “Bombingham” because of the frequency of racist dynamite terrorism. Carter was regularly in Nashville.

The Nashville Ku Klux Klan was very active during this time. People carrying KKKK (Knights of the Ku Klux Klan) signs are ubiquitous in photos of crowds protesting integration. And there’s a great deal of evidence that our Klan was radicalizing and working with an extremely violent renegade offshoot of the Klan out of Chattanooga — the Dixie Knights (or as they would quickly become known, the Dixie Klan).

Then there’s J.B. Stoner. Stoner was an insurance salesman who grew up on Lookout Mountain in Georgia. He was pen pals with a genuine German Nazi before World War II. He helped restart the Klan in Chattanooga when he was a teenager, and he was twice kicked out of Klavern No. 317 for being too anti-Semitic. (Interestingly enough, Klavern No. 317 was kicked out of the Klan in late September or early October 1957 for being too violent.)

Stoner was in town at the time of the Hattie Cotton bombing, and all circumstantial evidence suggests he was the JCC bomber. We know from informants that he appeared to be planning something in Nashville after the JCC bombing, and he was regularly in town visiting John Kasper.

So why don’t we know what role, if any, these folks played in the Looby bombing? For one, with very few exceptions, the Nashville city police records before 1963 are gone. You’d think a political assassination attempt would have been one of the few exceptions, but apparently not. For another, no one knows where the files of the precursor organization to the TBI are, and even if those files were found, it’s not clear I’d have legal standing to see them. And most importantly, before now, no one has managed to track down the FBI’s file on the Looby bombing. When I contacted the FBI about it three years ago, they told me the file had been destroyed.

Thanks to U.S. Rep. Jim Cooper, I now know that the file exists, and I’m hoping to be able to get a hold of it this summer. Meanwhile, in this excerpt from Dynamite Nashville: The KKK, the FBI, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control (out via Third Man Books in early 2021), I try to lay out what we can know about the Looby bombing from taking another look at the facts currently available to us.

An excerpt from author Betsy Phillips’ Dynamite Nashville: The KKK, the FBI, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control, scheduled for release via Third Man Books in early 2021.

Our local Klan leader Emmett Carr had an unbreakable alibi for the bombing of Z. Alexander Looby’s home on April 19, 1960. He’d been dead fifteen days.

John Kasper’s alibi was pretty good, too. He was in the Nashville workhouse.

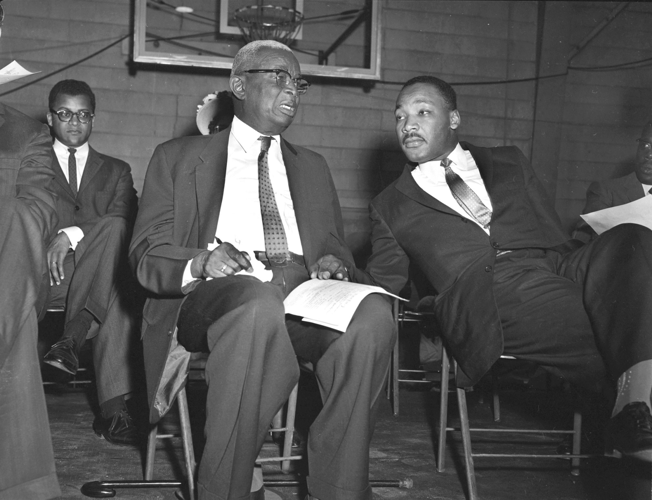

The general understanding of the bombing is that the sit-ins were going on; Looby was one of the lawyers for the protesters; Looby’s house was bombed because of that; the protesters marched downtown and Diane Nash asked Mayor Ben West to desegregate downtown; he did; and then Martin Luther King Jr. came to town to tell us how awesome and inspiring we were.

One of the reasons we think this is that the Tennessean reported that Looby thought the bombing was because of his legal work on behalf of the sit-in protesters who were trying to desegregate downtown businesses and regularly getting arrested. But the sit-in movement had been going on for weeks. There hadn’t been some kind of action or event that would seem to have galvanized racists into violent acts. At first glance, it just appears they picked a random day to bomb Looby.

Without the FBI files or police files, without any suspects, without any precipitating event that obviously inspired the bombers, how can we even begin to say why Looby was bombed, let alone who did it? Let’s all shake our heads and give a collective shrug and move on with our lives.

The story as we know it has the excuse for the bombing’s unsolved status built right in.

But once you start to dig into the bombing, even a little bit, a clearer—though not entirely clear—picture begins to emerge.

Let’s start with the bit where there don’t seem to be any precipitating events, no build-up to this bombing. First of all, now we know that segregationists in Nashville had been targeting Looby by name since 1957 (or earlier, if we count the note with the crossburning). We also know that the FBI had good reason to believe Kasper was trying to figure out how to assassinate Looby in 1958. And we know that Looby was at least tangentially tied to our two previous bombings.

Then there’s this: on April 5, 1960, the Tennessean ran a story informing everyone in town: “The Rev. Kelley Miller Smith [sic], president of the Nashville Christian Leadership council, announced that the Rev. Mr. Martin Luther King, president of the NCLC’s parent group, the Southern Leadership conference, will speak at the next mass meeting here April 18, ‘if we can find a place big enough.’ (Talley)”

Martin Luther King didn’t come to town in response to the Looby bombing. The Looby bombing was, it appears, planned to be a response to the meeting King was supposed to have on the 18th.

The April 5 announcement must have pissed racists off, or at least pissed off some small group of racists enough to plot to do something dramatic.

Z. Alexander Looby and Martin Luther King Jr.

I think John Kasper knew something was in the works, too. Look at why the Tennessean reported he was dissolving the Seaboard White Citizens Council on April 17, 1960.

The 30-year-old segregationist said the council he organized in 1956 is being taken over by neo-Nazis and he wants no part of them.

“I am nearly broken by jails, niggers and rock quarries and the cruel life that this is,” Kasper recently wrote a former associate from the Davidson county work-house where he has been confined for about three months. “I have a definite fear of being railroaded to jail again for something I don’t believe in.” (Harris, Kasper to Dissolve Own Citizens Council)

Sure, yeah, maybe he’s talking generally. Of course, it’s a safe bet that neo-Nazis might do something in the future that he’s going to get blamed for. But two days in the future, Looby’s house is going to get blown up.

There’s no further mention in the white papers of this King rally until April 19, when a Tennessean story announced, “A mass meeting to hear Dr. Martin Luther King will be held at Fisk university gymnasium tomorrow night, instead of at War Memorial auditorium, as originally scheduled (King’s Speech Location Moved to Fisk University).”

Which, oops, if your plan was to bomb the Looby house in response to the King rally, you’ve just bombed the Looby house only to grab a paper and discover the rally didn’t happen the night before.

Then there’s the story of the bombing itself, which also becomes more complicated when you look a little more closely at it.

Civil Rights attorney, NAACP leader, and sitting city councilman Z. Alexander Looby’s house was bombed at 5:30 a.m. on April 19, 1960. The blast damaged Looby’s home at 2012 Meharry Blvd., his neighbor’s home on one side and the apartment building on the other side. It also shattered 147 windows across the street at Meharry Medical School. Police chief Douglas Hosse told the Tennessean that “If that bomb had gone in the window, Looby’s house would have been blown off the face of the earth (Anderson).” Hosse told the Tennessean that he thought it was a bomb made up of ten or twenty sticks of dynamite “thrown from the street at a picture window in the front of Looby’s house. The bomb apparently missed the window by about four feet, fell to the ground and exploded at the foundation as the bombers drove away.”

Aftermath of the 1957 bombing of Hattie Cotton Elementary School

I spent an afternoon at the NAACP listening to old men reminiscing about Looby, who they relayed was always a snappy dresser, and the old neighborhood. Cars, they said, usually lined Meharry Boulevard. So we’re supposed to believe that someone in a car on the street threw a five to ten pound package out a car window, possibly over a parked car, up a slight ridge, and maybe 50 feet to Looby’s house on the first try? Well, put out an all-points bulletin for a racist shot putter with some quarterback experience, because who else could have done it? We’re talking about someone tossing the equivalent of a bowling ball at the house from a car.

In the other bombings, initial reports were also that the bombs were tossed from passing cars. Only later was that revised to the bombs having been carefully placed. I think we have to guess that the same is true here. Because Looby’s house didn’t appear to be destroyed, white Nashville quickly assumed that the bombing was more cosmetic than deadly, just as the other two bombings had turned out to be. The kinds of follow-up stories that happened with the other two bombings didn’t happen in Looby’s case. We know very little about whether and how the police might have revised their thinking on the Looby bombing. But the house and his neighbor’s house had to be condemned. We do know that. Both Hattie Cotton and the JCC could be fixed. Looby’s house could not.

I think the bomb was placed near the corner of the house deliberately, to try to ensure that, if the Loobys weren’t killed in the blast, they’d be killed by the house falling over and collapsing onto them. But what the bombers likely didn’t know was that the Loobys’ cute brick house hadn’t always been brick. A photo in the Looby collection at Fisk University shows that same house, but with light-colored wooden siding. If you look closely at the bombing photos, you can see that wooden siding under the brick.

I didn’t find any information about why he bricked up the house or when, but I am tempted to assume it was to make the house harder to set on fire—a common danger civil rights leaders faced. But this also meant that the outside walls of his house were much thicker than the bombers would have expected.

Something else, though, about the placement of the bomb may tell us something about the bombers. An alley ran behind Looby’s house. It still runs down the middle of that block. Looby’s driveway ran the whole length of his property—from the street to the alley. Directly behind Looby’s house—right across that alley—was the office for the organizers of the sit-in protests. Another really juicy target. Across the street from Looby’s house was the hospital, where people would have been coming and going at all times of night.

The bombers would have been much better served to use the alley and to plant the bomb under Looby’s bedroom. Their chances of being seen if they were on the street were fairly high (though not high enough, apparently) and their chances of being seen in the alley were very low. Plus, they then would have literally been bombing the sit-in office’s backyard. Why didn’t they use the alley?

A plaque marking the 1960 bombing of civil rights leader Z. Alexander Looby's home

I’m guessing it’s because they weren’t familiar with the neighborhood. I don’t think they knew there was an alley. This differs from the Hattie Cotton bombing, where the bombers knew how to get out of a rabbit warren of a neighborhood with no problem. Also, it suggests that, unlike the JCC bombing, they hadn’t staked out their target and considered how to use the landscape as cover. There has long been a persistent rumor among whites that black people blew up Looby’s house to “have an excuse” to demand the desegregation of downtown. This makes no sense just on the level of “you don’t kill a city councilman who’s on your side,” but black people in segregated Nashville knew Jefferson Street, the street on the back side of Looby’s block, which was the main street through the area that functioned as the black downtown. They knew the neighborhood between Fisk and the historically black public university, Tennessee State University (TSU—at the time Tennessee A & I). They would have known about the alley.

I also think the timing of the bomb is a clue. The generally-sympathetic-to-the-Civil-Rights-protesters Tennessean published in the morning. The more conservative Banner was the afternoon paper. By the time the Banner came out, Civil Rights protesters had already gone downtown and confronted Mayor West. What would have obviously been the biggest story of the day in the morning—the Looby bombing—was old news by the time the Banner hit newsstands.

And the bombing happened late enough in the early morning that the Tennessean was already being delivered when it happened. That meant the Tennessean’s first story about the bombing was the next day. If you needed to give your bombers a window of opportunity to get out of town before anyone even knew to look for them, you couldn’t have planned it more perfectly.

I also wonder about the police approach.

They canvassed the area repeatedly looking for someone who might have seen something, and the most they got out of it was that someone had seen an older model car with two white guys in it. The police don’t appear to have gone back to the Whites Creek guys to see what they were doing that morning. They don’t seem to have checked in with any of the suspects in the JCC bombing. There’s not even a report of them going to talk to Klan leaders to see what they might have to say.

The police sent officers to guard the homes of the following people: the mayor, Ben West; Rev. Kelly Miller Smith; Councilman Robert Lillard; Dr. C. J. Walker, the chair of the citizens liaison committee for the Nashville Christian Leadership Council; and Dr. Stephen Wright, the president of Fisk University.

In retrospect, those seem like obvious places to guard. But why did they think that the day of the bombing? The past two bombings had been spurred in part by Judge Miller’s actions or a hatred of him. How did they know they didn’t need to protect him in this case?

I don’t want to inadvertently downplay Rev. Kelly Miller Smith’s importance to the Civil Rights Movement when I ask this, but it’s a question we need to consider—why guard Smith’s house? Smith wasn’t the only clergy supportive of and active in the Civil Rights Movement. Just as an example, we talked about Clark Memorial Chapel hosting desegregation talks, which John Kasper attended, and getting a bomb threat in response. How did the police know they didn’t need to guard that parsonage?

As well, students from every historically black college and university in town participated in the sit-ins. Why would the police guard Fisk’s president and not TSU’s?

The only way the police’s strategy of who to guard makes sense is if we look at it with Dr. King’s presence in Nashville in mind. King and Smith were dear friends. When King came to town, he almost always stayed with Smith. I didn’t find any confirmation that King was with Smith on this particular stay, but it’s a pretty safe bet. The Nashville Christian Leadership Council was the local branch of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council. Walker and King worked closely together to coordinate strategies of resistance to segregation. Looby was one of the lawyers representing the sit-in protesters, who were under the guidance of the NCLC. And, of course, King spoke at Fisk.

In other words, the police behaved as if the attack on Looby was a threat against King.

Then there’s this: the police quickly got a confession. According to the Nashville Banner, two days after the bombing, Lucian Arzo Neely 1 was arrested after drunkenly telling a bunch of people at the Tennessee Theater that he had bombed the Looby house. He told the two police officers who arrested him that he had done it, and the next morning, after he’d sobered up, he told three detectives he’d done it. For reasons that are unclear in the story, even after his sober confession, one of the detectives told the Banner “the statements he made Thursday night undoubtedly was alcohol speaking (Confession of Bombing Discounted).” Neely was only charged with being drunk in a public place.

Neely seems to be a very, very poor suspect, confession aside. He didn’t seem to have any trouble before this incident, and he didn’t seem to have any trouble after this incident. According to the Banner story, he was an interior designer. According to the city directories, he was a painter. Neither profession gives you a lot of access to or experience with dynamite.

But here’s the thing that might make you wish the police had taken a little more time with him, and had the inclination to try to dig down into why a man they feel certain is not guilty of this crime would confess to it. Neely lived at 2113 Scott Ave., two blocks away from where police found John Kasper the night of the Hattie Cotton bombing.

[1] Old folks may remember that Looby had a black political rival named Neely. This is not him. This Neely was white.