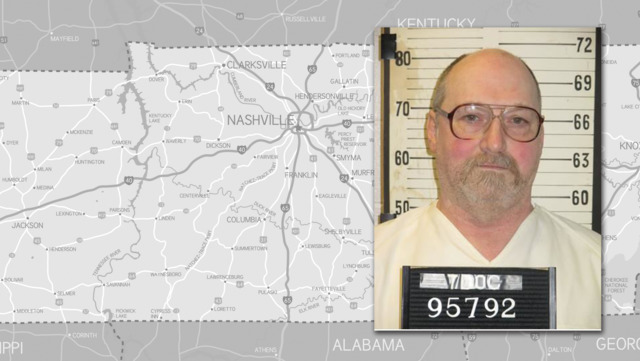

David Earl Miller

When the curtains opened at 7:12 p.m. Thursday night to reveal the execution chamber, David Earl Miller was already strapped and buckled into the electric chair. Like Billy Ray Irick and Edmund Zagorski, the two men executed before him in the same chamber earlier this year, Miller wore a beige Tennessee Department of Correction uniform. His head was shaved, his eyes cast down toward the floor.

As one of seven media witnesses seated just feet in front of him on the other side of a large window, I wondered what Miller’s dreams had been like this week. He was Tennessee’s longest-serving death row prisoner, having been there for nearly 37 years. And in 2002, according to court records, he told a clinical psychologist that he’d had a recurring nightmare about his execution.

"I'm at my execution, strapped to the gurney so I can't move at all, and my stepfather is present," Miller told Dr. David Lisak, according to documents included in Miller's application for clemency. "I see him sitting in the viewing gallery. I don't see any expression on his face, but I hear him say this to me: 'I hope you have nightmares about this you sorry bastard!'"

Reality turned out to be a nightmare of a different sort. Faced with a choice between a three-drug lethal injection protocol (which medical experts have said amounts to torture) or the electric chair, Miller chose the latter. He indicated his preference in a hastily written note to Riverbend Maximum Security Institution Warden Tony Mays. Miller was one of four death row prisoners who filed a lawsuit asking to be executed by firing squad, but the suit hasn't been successful so far.

As for the viewing gallery, no one from Miller’s family or the family of his victim, Lee Standifer, was there to see him put to death.

“I don’t see that it accomplishes anything at all," Standifer’s 84-year-old mother Helen Standifer told the Scene earlier this week. "It’s immaterial. It doesn’t bring my daughter back, it doesn’t accomplish anything. Frankly, I don’t see any reason to be there.”

Miller is the second Tennessee prisoner to be electrocuted in as many months, and the third man executed in the state this year. All three had a history of mental illness, childhood abuse or both. The death penalty in Tennessee is up and running again after having been dormant for nearly a decade, with six more executions scheduled in the next two years.

Having witnessed Billy Ray Irick’s lethal injection in August, I underestimated how unnerving it would be to feel familiar with the whole production — to know the conference room where a TDOC staffer would offer coffee, to remember the route to the execution chamber, and to notice subtle changes in the prison’s lobby. On Thursday night, there was a Christmas tree covered in lights, and a new sign at the security desk reading, "You can’t have a good day with a bad attitude, and you can’t have a bad day with a good attitude.”

The history of the death penalty shows, though, that even something as specifically scripted as an execution can turn into a spontaneous disaster. Although the executioners had been through this same process just five weeks earlier, Miller’s execution still felt like a mad experiment. What will happen when we strap a man to a chair, plug it in and send two cycles of 1,750 volts through a helmet on his head and down through the rest of his body? Will he burst into flames, as happened during two electrocutions in Florida in the 1990s? Or might he survive, the way an African-American teenager named Willie Francis did when Louisiana’s electric chair malfunctioned during his attempted execution in 1945? (After technical adjustments and failed appeals, the chair finished him off two years later.)

In the end, Miller’s execution went as planned. When the warden asked him for his last words, Miller uttered something that was unintelligible from the viewing gallery. The warden gave him another chance, and my fellow journalists and I, after conferring with Miller’s attorney, determined what he’d said: “Beats being on death row.”

Two TDOC guards in the room fastened the leather helmet and a wet sea sponge onto his head. As saline solution from the sponge poured down Miller's face, one of the men wiped him with a towel. A facility maintenance staffer plugged in the chair, and less than a minute later an exhaust fan kicked on. Then came the first jolt of electricity, quieter than you’d expect, like the sound of a humming guitar amp suddenly turned up to full volume.

Miller’s body thrust up from the chair against the restraints, staying there for around 20 seconds before falling back into the seat. Then again. And then, as far as we could tell, it was over. He did not appear to be breathing. At 7:25 p.m., the warden’s voice came over the speaker system.

“That concludes the execution of inmate David Miller. Time of death 7:25. Please exit at this time.”

In many ways, Miller’s life was also one long cruel experiment. Take a young boy, who first experienced alcohol's influence in his mother’s womb, and see his basic humanity violated by everyone close to him. See him first sexually assaulted when he was just 4 or 5 years old by a cousin and later, according to court records, by one of his grandfather’s friends. See him raped and sexually assaulted by his mother — herself living with a brain damaged by toxins from the plastics plant where she’d worked — who would also whip him with a belt, an extension cord, a wire coat hanger or an umbrella. Then introduce a stepfather, an angry drunk who took physical abuse to another level. On one occasion recorded in court documents, Miller's stepfather “knocked David out of a chair, hit him with a board, threw him into a refrigerator with such force it dented the refrigerator and bloodied David’s head, dragged him through the house by his hair, and twice ran David’s head through the wall.”

According to those documents, by age 10, Miller had twice attempted to kill himself and had begun drinking alcohol. He would go on to abuse psychotropic drugs that mingled with what was by then a documented history of psychotic episodes. Miller and his siblings were removed from their dilapidated home at least once, but soon returned. As a 16-year-old, he allegedly tried to rape his mother at knifepoint. He told mental health professionals in prison that he didn’t remember a single time his parents told him they loved him. And when his mother died, her obituary reportedly made no mention of him.

Can the angry, violent young man who emerged from that childhood truly be a surprise?

Lisak, the clinical psychologist who evaluated Miller in 2002, wrote in a report that Miller’s attempts to successfully adapt to adult life “were ultimately undone by his meager reservoir of coping resources, by the tragic death of his grandfather, and by the deep wellspring of rage that he harbored."

"This rage," Lisak continued, "that was periodically directed at women and that ultimately was directed at Lee Standifer, stemmed directly from the incestuous abuse he suffered at the hands of his mother, and from the brutal physical abuse he suffered at the hands of his step-father."

Of course that doesn’t diminish the horror of what came next.

Miller would later be accused of raping two other women, although the charges were dropped when they declined to participate in the prosecutions.

Lee Standifer did not ask to be a part of this experiment. Her mother remembers her as an upbeat girl who’d found a job at a meat-packing facility in Knoxville that suited her well. She was living successfully on her own, with an intellectual disability that her mother says never really bothered her.

By then, Miller had drifted homeless to Knoxville, and was living with a 50-year-old Baptist preacher, the Rev. Benjamin Calvin Thomas. Court records say the preacher picked up a a hitchhiking Miller, and trapped him in a coercive relationship, exchanging room and board for sexual activity.

On May 20, 1981, Miller and Standifer went on a date. Miller, according to court documents, had been drinking heavily and taken LSD. His attorneys have argued for decades that what happened that night cannot be separated from everything that came before, from the drugs, the beatings, the years of sexual abuse and the pattern of psychotic episodes.

According to court documents, Miller struck Standifer multiple times with a fireplace poker, killing her, and stabbed her dead body at least six times. One stabbing appeared to have occurred with such force that the state’s medical examiner suggested the knife might have been driven into Standifer’s body with a hammer. Her body was found with her hands tied, near a wooded area some 60 feet from the home the two had been in.

Prosecutors asserted at Miller’s trial that the murder had taken place after Miller sexually assaulted Standifer. But while the state’s medical examiner found evidence that sexual intercourse had taken place, Standifer’s body showed no signs of sexual assault. The court determined that there was not enough evidence of sexual assault to put it before the jury. Later, during Miller’s sentencing, a different judge allowed prosecutors to present that charge to a jury, but the jury rejected it.

In an application for clemency sent to Gov. Bill Haslam last week, Miller’s attorneys wrote, "If this case were tried today, David would not be sentenced to death and it is likely he would not even be convicted of first degree murder." He was convicted, they wrote, before a pivotal U.S. Supreme Court decision that would have required that he have a mental health expert available to explain his history, and its possible connection to his crime, to the jury.

Haslam rejected Miller’s plea for mercy a little after noon on Thursday.

Standing in the cold, under a tent in the Riverbend parking lot, Tennessee Department of Correction spokesperson Neysa Taylor read a statement from someone identified only as "a victim" from Ohio: "After a long line of victims he has left, it is time to be done. It was time for him to pay for what he has done to Lee." Later, Miller’s longtime attorney Stephen Kissinger addressed the assembled media.

“David Miller was a friend, a father and a grandfather,” he said. “During our last conversations, one of the things he talked about was the opportunity he had to make just a handful of close friends. He mentioned Nick and Gary and Leonard, and if those guys get a chance to hear this I want them to know that they were with him until the end. He talked about his daughter, Stephanie, and his grandchildren.”

Miller's daughter spoke to the Scene earlier this week about first meeting her father at age 12, when he’d already spent a decade on death row. And in nearly 37 years on the row, Miller certainly had made friends. One person who visited the unit on Monday, before Miller was taken to death watch, told the Scene that a line had formed outside of Miller’s cell. The condemned men of Riverbend’s Unit 2 were saying goodbye to another one of their fellow prisoners. Miller gave one of them his postage stamps and a paint-by-numbers kit before he was taken away.

Outside, after the execution, Kissinger continued: “And if any of you have been reading what we submitted to the governor, what we’ve been saying to the courts for the last 20 years, you’ll know that he cared deeply for Lee Standifer and she would be alive today if it weren’t for a sadistic stepfather and a mother who violated every trust that a son should have. I know I came up here promising to tell you what we did here today, but I think maybe what I should be doing is ask you all that question. What is it we did here today?”

From down the street, in the field reserved for the public to demonstrate for or against the execution, a group that has gathered there three times now was huddled in the cold. David Bass, a death row visitor who attended Thursday night’s vigil as well as one in the same spot for Edmund Zagorski last month, texted an observation after the execution.

“No TV cameras at all with us,” he wrote. “No yelling from the protester. Seems like it is getting routine. Scary.”