Edmund Zagorski had been dead for several minutes by the time word reached a group of around 40 death penalty opponents who’d been holding a vigil in a field adjacent to Riverbend Maximum Security Institution. It was as if the news had been carried on the cold wind that whipped north from the prison.

Joe Ingle, a United Church of Christ minister who was Zagorski’s spiritual adviser and has been a friend to death row prisoners across the South since 1974, announced to the crowd that the execution was complete. They began to sing “Amazing Grace.”

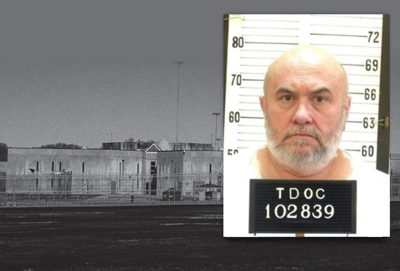

Zagorski was put to death in the electric chair on the evening of Thursday, Nov. 1. He had received the death sentence from a Robertson County jury 34 years ago after he was convicted of killing John Dale Dotson and Jimmy Porter. The two men had met Zagorski in the woods of Hickman County with plans to purchase 100 pounds of marijuana. Prosecutors said Zagorski shot them, slit their throats and stole their money. He was later arrested in Ohio after a shootout with police.

Six of the jurors who convicted and sentenced Zagorski more than three decades ago now say they wouldn’t have voted for the death penalty if they’d had the option of life without the possibility of parole, a choice that is now available to all capital-case juries. They spoke publicly in support of clemency for Zagorski, as did death row staff who attested to his rehabilitation and the exemplary life he has lived in prison. In his application for clemency, one correctional officer recalled Zagorski breaking up a bloody fight between two inmates. A former warden said, “Ed is a perfect example of how a man can change for the better over the years.”

But Gov. Bill Haslam declined to show Zagorski mercy. Minutes before the execution began, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to grant him a stay, rejecting his arguments against the constitutionality of the electric chair.

Zagorski is the first Tennessee prisoner killed by electrocution since the 2007 execution of Daryl Holton. He is the 127th person, all of them men, to die in a Tennessee electric chair, a device that is said to contain the grim legacy of Tennessee executions. First used in 1916 to execute Julius Morgan — a black man who reportedly was nearly lynched by a mob after being accused of raping a white woman — the original chair was said to have been built out of wood from the state’s old gallows. In 1989, Tennessee contracted a self-made execution device dealer and Holocaust denier, Fred A. Leuchter Jr., to rebuild the chair. He did so utilizing wood from the original.

Days before Thursday night’s execution, Leuchter told the Associated Press that the chair was “defective and shouldn’t be used.” In the end, though, it appears to have worked as intended.

Like Holton, Zagorski chose the electric chair over lethal injection. He and his attorneys argued until the end that both electrocution and Tennessee’s lethal injection protocol — the latter of which was used to execute Billy Ray Irick in August — are unconstitutional. But in the end, Zagorski decided that death in the chair would be quicker than a three-drug cocktail that medical experts have said is akin to being buried alive and burned alive. He was originally scheduled to die on Oct. 11, before the governor granted him an 11th hour reprieve to give executioners time to prepare for an electrocution.

“Horrifically, Mr. Zagorski was forced to choose between 10 to 18 minutes of chemically burning from the inside while paralyzed or being literally burned to death in less than a minute,” Kelley Henry, Zagorski’s attorney, said during a press conference following the execution. “He should never have been forced to make that choice. Neither of Tennessee’s current options for execution are humane or constitutional. The state must find a better method of execution that comports with the innate dignity of all human beings and the constitutional protection from torture.”

Media witnesses described Zagorski’s final moments. NewsChannel 5’s Jason Lamb said that as Zagorski sat in the chair before the execution, the inmate looked at Henry, who’d been with him minutes earlier as guards strapped him into the chair. According to Lamb, Henry nodded, smiled, and tapped her chest over her heart.

“We did have the understanding that if I was placing my hand over my heart, that meant I was holding him in my heart,” Henry explained later.

Asked if he had any last words, Zagorski replied, “Let’s rock.” In October, Zagorski told the Scene that the song he’d have in his head when prison guards took him to death watch — a period when the inmate is placed under 24-hour supervision in a small cell next to the execution chamber — was “Flirtin’ With Disaster” by the Southern-rock band Molly Hatchet. He was a former motorcycle enthusiast known to other bikers as “Renegade.”

The Tennessean’s Adam Tamburin described Zagorski grimacing as guards fastened onto his head a helmet and a sponge soaked in saline solution — to help conduct the electricity. As the solution ran down Zagorski’s face, guards wiped it off. Minutes later, Tamburin said, witnesses could see as a guard plugged in the chair.

According to the media witnesses, Zagorski’s arms appeared to turn red as the first cycle of 1,500 volts of electricity began to run through his body. He rose up in the chair, his whole body tense as the current traveled through him. Then, a brief pause. During this time, Henry said, she could see his belly continuing to rise and fall, indicating that he was still breathing. Then a second cycle of 1,500 volts.

Zagorski was pronounced dead at 7:26 p.m.

“Mr. Zagorski spent the last 34 years on death row living as a model inmate, even saving the life of a guard,” Henry said, holding back tears as she spoke to media after the execution. “He was loved by many and leaves behind numerous friends. The world is not safer because of his execution, and justice was not served tonight.”

He was indeed beloved by his fellow death row prisoners. Before Zagorski was taken to death watch days before his original execution date in October, more than a dozen of the men on death row pulled together various ingredients and made pizzas — a last supper of sorts before he left. In Riverbend’s Unit 2, which houses death row, Zagorski was known only as “Diamond Jim.” It’s an example of the gallows humor and intimacy that exists among Tennessee’s condemned prisoners — Diamond Jim was the nickname of a man who helped authorities catch and convict Zagorski three decades ago.

Just down the road from the prison, another part of the death penalty ritual had been playing out in the hour leading up to Zagorski’s execution. Just as they had in August before Irick’s execution, a group of death row visitors, clergy and other death penalty opponents gathered in a designated area to hold a vigil. Armed law enforcement officers stopped each person as they arrived in their vehicle, like a macabre version of greeters sorting guests at a wedding: “For or against?” the officers asked each person. Other officers sat at a table outside the two separated areas. Everyone was made to sign in on a sheet of paper, indicating whether they were “For,” “Against” or “Media.”

Only two men showed up to cheer on the execution. Something like a real-life personification of the comments section that appears under any article about the death penalty, the men shouted taunts at the large crowd on the other side of the fence.

"It's not gonna make a difference!” one of the men shouted as the execution neared. “We're gonna kill your boy tonight! He's got five minutes left!"

"I hope he catches on fire!"

At one point, as the death penalty opponents prayed, one of the men shouted at them to “pray for the victims!” He must not have been able to hear the group’s prayers — they’d prayed for the victims and their families only seconds before.

In between prayers and denunciations of the death penalty, there were stories about Zagorski the man, a person who’d grown up in Tecumseh, Mich., and said he didn’t like to spend too much time at home because his mother suffered from mental illness. Advocates demanded he be seen as more than the worst things he’d done in his life. A bald man with a bulldog physique, Zagorski spent his time on death watch doing two things, mostly: dictating thank-you notes and expressing gratitude in other ways to the lawyers and others who’d helped him over the years; and doing push-ups. Ingle told the crowd that during his first stint on death watch last month, Zagorski did 12,000 pushups. This time he did 22,000, and stopped late Wednesday afternoon.

David Bass, a death row visitor, shared a story he’d heard from Zagorski himself, one Ingle also recently shared with the Scene. Before his arrest and conviction, Zagorski had worked as the captain of a boat in the Gulf of Mexico that ferried people and supplies to and from an oil rig. One day, there was an explosion at the rig. At Zagorski’s behest, the story goes, he and two other men on the boat with him at the time went back toward the flaming platform and ended up assisting in the rescue of more than 20 people. Bass said that when he expressed shock at the number of people they’d rescued, Zagorski conceded that he’d probably saved only 16 people by himself.

Although the Scene could not definitively confirm the details of the event, or Zagorski’s involvement, the story does seem to match an event that took place in the Gulf in 1980: Texas newspapers at the time reported on an explosion at an oil platform operated by Pennzoil and staffed, in part, by Poole Offshore Co. — the company Zagorski said he’d worked for. The explosion killed four people and injured 29.

Standing in the field as the crowd dispersed, speaking into a strong wind, Ingle repeated what he told the Scene last month after Zagorski’s execution was called off — he does not believe that Zagorski is the one who killed John Dale Dotson and Jimmy Porter.

“The real tragedy here, and it is a tragedy, is I’m convinced he did not kill those two people,” Ingle said. “He’s been killed for a crime he didn’t commit. He was there, but he didn’t kill those people. It’s a real shame that the people who are running this state are more interested in putting people in the execution chamber than getting to the truth.”

Zagorski did not testify at his trial in 1984, but questions about what exactly happened that night in the woods of Hickman County have been raised in court filings and by advocates over the years. Zagorski gave different versions of his role in the events after his arrest. His lawyers have challenged a confession he gave, as well as other damaging statements, arguing they were the result of horrible mistreatment in a Robertson County jail. A court filing from earlier this year reads as follows: “Zagorski was placed in solitary confinement in an unventilated metal hotbox for seven (7) weeks during the heat of the summer, which decimated him physically and mentally, made him mentally ill and suicidal, and led him to give statements in order to end the unbearable conditions."

But Zagorski was, by all accounts, at peace on Thursday night. Henry said during his last three days on death watch, Zagorski had worked to put everyone around him “at ease.” On Wednesday night, Ingle said, Zagorski had what he described as a dream or a vision that left him “good to go.”

“It was the grace of God in the most barbaric circumstances,” Ingle said. “That’s what it was.”

Zagorski’s upbeat attitude — his smile and seemingly unfazed attitude in his final statement — did not sit well with family of the two men he was convicted of killing. For them, the past 34 years have consisted of a horrible wound that begins to close, only to be reopened by another appeal, another court hearing, another graphic news report of two murders that had changed their lives forever. Kim Dotson Rochelle, the daughter of John Dale Dotson, told The Tennessean Thursday night: "He had no remorse for what he did. He was smiling just like he was when he was caught. That's why he got just what he deserved."

Zagorski has family too, of course. In the days leading up to his execution, Henry said he’d received messages from Zagorski’s ailing mother, as well as other relatives.

Whatever the state of Zagorski’s conscience Thursday night, he seems to have been concerned about the burden that might have been weighing on others. Describing the moment when prison guards came to his cell to extract him before the procession to the execution chamber, Henry said Zagorski addressed the guards who were about to lead him to his death.

“First of all I want to make it very clear I have no hard feelings,” Zagorski told them, according to Henry. “I don’t want any of you to have this on your conscience. You are all doing your job and I’m good.”

As they strapped him into the chair, Henry said, he told the guards that one of the saline sponges at his ankles, which would help conduct the lethal electricity that was about to shoot through his body, was a bit loose. They needed to tighten it.

He looked up at his attorney, Henry said, and offered two words: “Chin up.”