@startleseasily is a fervent observer of the Metro government's comings and goings. In this column, "On First Reading," she'll recap the bimonthly Metro Council meetings and provide her analysis. You can find her in the pew in the corner by the mic, ready to give public comment on whichever items stir her passions. Follow her on Twitter here.

In recent months, Nashville has played host to a series of Nazi demonstrations.

That’s right: Nazis.

It’s 2024, and we’ve got a Nazi problem. A bunch of losers cosplaying Rolf Gruber from The Sound of Music have made it their mission to ruin our weekends and cause chaos at the courthouse.

Reps. Jones and Hardaway speak out against hate group who hurled racist insults at the young street performers

Mayor Freddie O’Connell has put forward several pieces of legislation in an attempt to rein in the hatred, and about a month ago, Councilmember At-Large Zulfat Suara introduced a rule change to limit public comment at Metro Council meetings to Davidson County residents. Suara deferred the rule change in response to concerns from advocates who saw it as a barrier to participation for people experiencing homelessness, undocumented immigrants and Metro employees who have been priced out of living in Nashville.

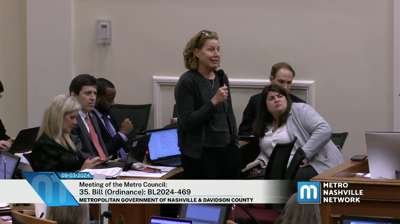

On Tuesday, Suara introduced a revamped version of her proposed rule change. The new rule — which was approved by the council, with only one no vote — limits public comment to Tennessee residents and requires public commenters to provide “acceptable proof of residency” when they sign up to speak. The council’s staff will determine what qualifies as “acceptable proof,” though Suara did provide some guidance during the council’s discussion of the change.

“It could be your driver’s license, your state ID, your library card, your WeGo card, your utility bill,” said Suara. Even a piece of mail would qualify.

Look. I get it. No one wants to hear people spew hatred on the Metro Nashville Network — or anywhere else, for that matter. But erecting artificial barriers to sharing your thoughts with your elected officials is anti-democratic. In this instance, it’s also an overreaction. When the Nazis showed up to the courthouse, they tried to sign up for public comment. But some dedicated residents were able to block them by signing up a bunch of their friends to fill up all the available slots. Ironically, if Suara’s rule change had been in effect at the time, they couldn’t have done that.

Councilmember Suara orders chamber gallery cleared after disruptions by a dozen loosely organized white supremacists

The council has changed the rules of public comment several times over the past year. Continuing to move the goalposts is unfair to the public, particularly when you’re solving for a problem that never actually materialized.

I’m constantly trying to convince people that the council is actually a super chill and fun place to be, and you should definitely show up for public comment. But having your ID checked at the door is decidedly uncool.

The rule change will take effect at the second meeting in October.

Out Over Their Skis

To get a bill passed through the council, it has to be “read,” or considered, three separate times. The first reading is typically perfunctory. Bills are approved on first reading en masse before being routed to the appropriate committee for discussion and a recommendation to the full council.

It’s exceedingly unusual for bills to be discussed in detail on first reading. Committees are where the finer points of legislation are debated and hashed out, and the council’s legal staff doesn’t provide analysis of pending legislation until second reading. That’s typically the point at which councilmembers propose amendments, argue for or against legislation, and fight it out on the council floor.

In past council terms, even some of the most controversial legislation passed without comment on first reading. This term, however, the council seems more willing to preempt committee discussions, working to kill controversial bills on first reading.

Councilmember Jeff Preptit was the target of just such an attempt at Tuesday’s council meeting. Preptit’s bill to prohibit police from associating with hate groups was on first reading, after he deferred it for several meetings to refine the language.

What’s Good for the Goose

Conservative Councilmember Jeff Eslick led an unsuccessful charge to kill Preptit’s bill, posing some rather puzzling questions to Metro Legal about the 2020 protest-turned-riot in downtown Nashville.

“Based on the actions a couple of years ago, where this building was on fire, cars were damaged, businesses were looted," Eslick said, looking self-satisfied. "Would that group be considered a hate group under this bill?” He really thought he was cooking, y’all.

“My point is: If that group was considered a hate group, how many firemen, how many police officers, and how many Metro employees would be ensnared in this new rule?”

Staff at the administration table looked on, dumbfounded, as Metro lawyer Lora Fox struggled to respond with a straight face. “My recollection about those riots was that they were not particularly organized,” she said, adding, “If someone was participating in violent behavior, it’s possible that they could be, uh, ‘caught’ by this, so to speak.”

Personally, I’m OK with the police getting in trouble if they try to burn the fucking courthouse down, but I guess that makes me a radical socialist?

Eslick went on to question who would define a “hate group” — a term that is explicitly defined in Preptit’s substitute bill to include “any person or group that incites or provides material support for criminal acts or criminal conspiracies that promote violence” toward various classes of individuals.

Preptit’s substitute removes much of the more controversial language from his original bill, including a provision that would have prohibited mere “association” with such groups, including social media activity such as “likes” and retweets of hateful material. The substitute replaces this arguably — though, like, not actually — more “passive” embrace of hatred with active, knowing participation in the activities of criminal hate groups or paramilitary gangs. It also expands the prohibitions to the Nashville Fire Department, in light of concerns that the original language targeted the police.

I’m sorry, but how the hell could you possibly have an issue with that language? How exactly does one accidentally become “ensnared” in the criminal activities of a paramilitary gang? What is the edge case here that we need to be concerned about?

And perhaps most importantly: Why would there be any pushback to a policy that, at its core, requires the police and other public safety personnel to follow the law and respect the people they serve? As proponents of mass surveillance — including those very same police — love to say, “If you’re not doing anything wrong, you don’t have anything to be worried about.”