Making blue pigment at home

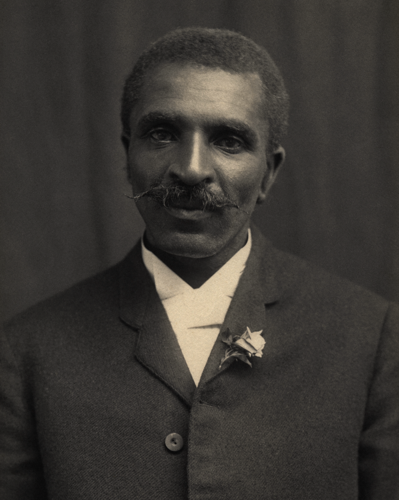

Back at the beginning of December, I read an article about how Chicago-based artist and architect Amanda Williams had revived the process George Washington Carver used to produce a blue pigment using regular old Alabama clay. This blew my mind. Imagine being able to take clay from your own yard and make blue pigment.

OK, let’s back up here just a second. Here’s what you need to know about natural pigment. If you want a yellow or a brown, you barely have to try. I’ve gotten lovely, almost-electric yellows from Queen Anne’s lace and more golden-yellows from Osage orange wood. Brown? You got a pile of walnuts slowly rotting in your yard? Then you also have some really lovely browns. Reds are rarer, but still pretty common. Greens are also pretty common, but tend to fade easily.

But blue? You’ve got two choices: Indigo or woad. Both, back before the advent of better production methods, required a large amount of urine to extract the pigment from them. Ask me if this works. Ask me how I know. Ask me how many years it takes to get the smell out of your nose. No, no. Don’t ask me. Just know that I know, and that knowledge came the hard way. Plus, with woad, to get the best results, you also need access to ice, which wasn’t easy for an Alabama dirt farmer to get access to back when Carver was inventing a way for people to get blue pigment.

Carver coming up with a way to get blue pigment without needing to house a five-gallon bucket of fermenting urine that you eventually have to put your hands in? Extraordinary.

I spent the holidays trying his technique. I got a hold of his patent application to see what he was up to. I saw “25 pounds of commercial sulphuric acid” and I laughed out loud. You have all these other directions about lifting and stirring and draining off, and I’m just imagining myself with an amount of sulfuric acid equivalent to the dog food bags I struggle to get in the house. I decided to drastically pare down the recipe, but keep the proportions the same. The only other change I made was that, since I couldn’t get nitric acid (thanks for nothing, meth heads and bomb makers), I used bloodmeal instead.

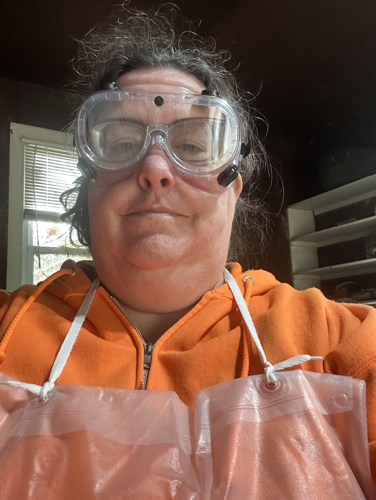

The author cosplays Breaking Bad

I live in the ancient Whites Creek floodplain, meaning my dirt is mostly clay. To process it into a clay I could use to make blue, I dumped it in a mesh strainer and rinsed through everything into a glass jar but the clumps of grass and big rocks that remained. Those I threw back outside. Voila, clay. (Note: If you're going to try to make something from the clay in your backyard, you should refine it more than this, but it’s totally doable.) I let it dry and then ground it up finely.

I collected all my ingredients, went out into my garage (with the garage door open), put on all my safety gear, and followed along with Carver’s patent. I don’t know if it’s because I had such a small amount of the ingredients, if I just had access to more pure chemicals than Carver did in his day or what, but the reaction was pretty instantaneous. And I didn’t need any extra heat. The chemical reaction produced enough heat to let me dissolve everything. And I had blue almost instantly.

I poured it into a container and stirred occasionally, but I mostly just left it alone. But I got to wondering — what was the clay for? Judging by the ingredients, and going back to the article that spurred my curiosity, I was just making Prussian blue. That doesn’t need clay.

So then I wondered if Carver was patenting a process he knew would work, but maybe, in his own lab, he was using the iron from the clay. After all, it’s iron that gives Alabama clay its famous red color. Using the chemicals I had left over, I ran the process again, but this time leaving out the extra iron — and I’ll be damned if that didn’t end up making tiny bits of blue.

That left me with one question: If Carver wanted to make blue pigment available to everyone, to make themselves, how was an ordinary person back in his day getting their hands on these acids? Well, it was because they’re in common household cleaners. And if they’re available in common household cleaners to me now, even after the century-long push of, “What if we didn’t poison ourselves and the world?” then I have to believe that analogous products existed in Carver’s day. So off I went to the hardware store to purchase said products.

I’m being vague here, because this did work, but it is a very bad idea. You absolutely should not try this, especially since you can get the pure chemicals online (except for the nitric acid) very easily and you can buy Prussian blue pigment even more easily. Mixing the two cleaners together (and let me state, once again as clearly as I can, that it says on both bottles not to mix them with other household chemicals, and I did it anyway and it was stupid) made a wave or a plume of noxious gas. It was so bad. I’m very glad I was in my garage. I wish I’d been wholly outside. It felt like I burned the whole insides of my sinuses.

You know how when some people buy a boat, their spouses go, “Oh cool, we got a boat!” And when other people buy a boat, their spouses go, “Why in the hell did you buy a boat?” This is that second group’s method of making Prussian blue. Don’t do it.

But now I had so much blue pigment. So much. I couldn’t figure out how to make it into a dye. So over I ran to Jerry’s Artarama and told them what I was up to, and they helped me pick out a watercolor binder so I could make my own paint. And I made blue paint! Out of clay from my yard. What ridiculous magic!

The article I read that set me off on this adventure explained:

For Carver, color was a tool to beautify the homes of the region’s poorest residents that could be achieved through natural resources. Like with his encouragement of local farmers to enrich themselves by growing bounteous crops (which included soybeans, pecans and sweet potatoes, in addition to peanuts), color was a key component of his plans for autonomy, dignity and prosperity for Black families in the South. He encouraged people to freshly paint their homes in bright colors, and wanted to provide the materials to do so.

George Washington Carver circa 1910

So beyond the resonance that this had with me as someone who makes her own pigments from time to time, and who self-traumatized with a urine vat, this blue pigment, made this way, means something deep about Carver’s hopes for and the care he had for his community.

I love that too.

My favorite thing about living in Nashville is that we have so many historically significant spots that you can just go see for yourself. And I never know what I’m going to learn from going to see things, but I always learn something. I know not everyone is as big a history nerd as me, but whatever it is you’re into, you can always learn so much from just trying something yourself — from making your own blue to making your own computer.

Even if all you learn is an appreciation for the fact that all this stuff is mass-produced for you these days.