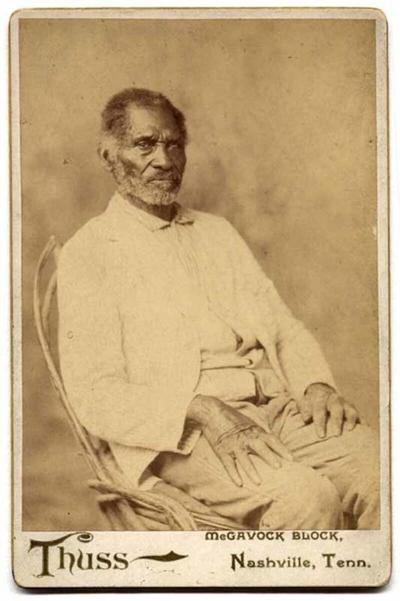

Alfred Jackson in Nashville, circa 1900

I’ve found something weird in the past. In 1860, the white Comptons who lived out along Hillsboro Pike down in District 11 owned 56 people. Now, I was taught that formerly enslaved people took the last names of their enslavers. Maybe not the very last people to own them, but someone who owned them. And the thing about the Comptons is that, by and large, from what I can tell, they weren’t buying and selling a lot of people. Meaning that, of those 56 people, most of them were born and raised enslaved by Comptons.

So I expected to find quite a few Black Comptons in District 11 in 1870, figuring that most people hadn’t yet had the opportunity to move away from where they were enslaved. There are 11 Black Comptons in the 1870 Census in District 11 who are old enough to have been enslaved by the Comptons. This does not count Henry Compton’s companion and their five children, who were Black, but who were all in Nashville for the 1870 Census.

For the sake of argument, let’s add back in Ann and the four of her children who we can say for sure were enslaved at birth. That’s still just 16 Black Comptons. I transcribed all of the Census data for 1870 and 1880 in Davidson County District 11, the neighboring District 8, and the three Williamson County districts that bordered those two districts to the south — 7, 15 and 16.

Focusing still only on 1870, there are no other Black Comptons in those districts. Just the 11 we counted two paragraphs ago. Then I was using the Census records to give me a very rough idea of where people lived in District 11, and I saw something even stranger: Only three Black Comptons lived close enough to the white Comptons to have been sharecroppers on their land. All the other Comptons, who all seem to be one large extended family, lived way south near the white Edmondsons.

The Black people living near the Comptons in 1870, who most likely would have been their formerly enslaved people, have last names like Moore, McCoy, Owen, Drake, Jackson, Brown and Edmondson, among others. We also know, thanks to government interviews right after the Civil War, that the Comptons’ slaves last names included Allen, Shute and Thompson.

A headstone carved by William Edmondson points to a story many decades in the making

OK, but maybe the Comptons are the exception that proves the rule. The last name Compton doesn’t necessarily reflect who was enslaved by the Comptons, but everyone knows that enslaved people got the last names of their enslavers, so it will hold true in other instances.

And these districts have some of the largest sites of enslavement in Davidson County: Travellers Rest (the Overtons), Belle Meade (the Hardings) and Edmondsons/Edmistons sprinkled all over the border between the two counties from Hillsboro Pike east to past Nolensville. There are 22 Black Overtons old enough to have been enslaved, and a sizeable minority — seven of them — don’t even live in the same district as Travellers Rest. There are 15 Black Hardings old enough to have been enslaved, and half of them live in Williamson County. For all the white Edmondson/Edmiston enslavers in the area, there are only 20 Black Edmondsons in that same area.

If you were going by count alone, considering that there are more than 80 Black Owen/Owenses in these districts in 1870, you’d assume that the white Owen family enslaved the most people in 1860. But the Owen family wasn’t some huge anomaly of enslavers, and they certainly didn’t enslave four times as many people as the Edmondsons did.

In a perfect world, these digitized Census records would be in huge publicly available databases so that a person could look and see if this holds true throughout the South. Or hell, throughout Middle Tennessee, or just even in all of Davidson and Williamson counties. We would — and should be able to — easily know how the last names of Black people in 1870 stack up against the last names of enslavers in 1860, and if formerly enslaved people were ending up with the last names of their enslavers, or if something else was going on, or some mix of the two.

However, until Ancestry.com becomes a lot more cooperative, we don’t live in that world. But what I can say is that, in these five districts, who enslaved you isn’t a great indicator of what your last name is.

So how are Black people in 1870 in these five districts ending up with the last names they have? I have a guess. A theory. But a theory I don’t know how to test. Yet, anyway.

One of the many horrible things about slavery was that enslaved people could not guarantee they could stay with their loved ones. Your children could be sold out from under you. You could wake up one day and find your neighbors gone with no idea where they went. Your father could be sold away. Your wife could be carted off by the slave trader. Newspapers after the Civil War were stuffed full of notices of people asking for word of the whereabouts of their loved ones. Of all the cruel and inhumane things people endured during enslavement, the constant threat and frequent reality of losing your loved ones had to be the most heartbreaking.

Whether or not this is where people from The Hermitage and Tulip Grove who died in slavery were buried, it's a spot that is historically significant

So let’s focus on Orange Edmondson, who was enslaved by Henry Compton and was still subsistence farming on Compton’s place in 1870. If someone’s looking for him and they know he was enslaved by Henry Compton, then he doesn’t need the last name Compton, because he’s still in the same place he was. “You know Orange who used to be Henry Compton’s slave?” “Orange? Yeah, he’s still in that same cabin.” But imagine that you were separated from Orange before he went to the Comptons. You’re asking about Orange who lived on the Edmondson farm. There’s no one named Orange on the Edmondson farm anymore, but a person could say, “Well, there’s an Orange Edmondson and his family up on the Compton farm,” and now you know to move your search for Orange northward.

I had this thought as I was contemplating Alfred over at The Hermitage. Alfred ended up being Alfred Jackson, but he and his wife and their kids were all Bradleys in 1870. His wife and kids stayed Bradleys even after Alfred went back to Jackson. Alfred’s whole family had been enslaved by Jackson — he himself, his wife, their kids, his mom, his dad, at least one grandmother, aunts and uncles. People he cared about and who cared about him knew where to find him. So right out of the gate, there was no need for him to be a Jackson. But as it became obvious that Alfred was going to become the person who was there at The Hermitage — the person who people who had been sent to Mississippi to work Jackson property there or who had been sold off over the years might come to for information on what had become of their loved ones — it would make sense for Alfred to make his connection to The Hermitage as clear as possible and to take Jackson as a last name.

I think at least some of the time, naming conventions were about making you as easily findable as possible. How common this was, I can’t say. But things are definitely more complicated than “this is the last name of my enslaver.” Sometimes I think it was more like, “Here is a beacon by which my loved ones can find me, if they are looking.”