City planners sometimes refer to downtown Nashville as a "black box" — people go in and people come out, but it’s not clear what exactly happens in between. Reactive traffic controls, street conversions, expanded vehicle permitting, new pedestrian and cyclists routes, and loading zone management all feature in the latest long-term strategy from the city’s transportation department.

Managing the public right-of-way is one of Metro’s really big responsibilities and among the most obvious city services in residents’ day-to-day lives. Known as the Nashville Department of Transportation and Multimodal Infrastructure (NDOT) after a 2021 rebrand under then-Mayor John Cooper, Metro’s transit team faces the daunting effects of a decade of explosive city growth and a growing residential neighborhood downtown. The unique boom-and-bust of weekend tourism presents an additional challenge of how to efficiently inject and extract thousands of people over a few hours on a few blocks. Lacking a signature mass transit network — and spurned by the historic failure to get one started five years ago — the city is left to work with what it has. In its latest Connect Downtown plan, the city bets on expanded bus service, tightly managed street space and networks for scooters, bikes and pedestrians.

To solve downtown, Connect Downtown aims to get people out of cars with safer and expanded infrastructure for pedestrians, scooters and bikes. The plan includes wider sidewalks, scooter corrals and a connected downtown greenway, and Metro will continue its push to make WeGo a desirable option with efficient and reliable routes that operate in dedicated lanes between the SoBro transit center, WeGo Central and a new East Bank bus center. From there, buses can send people out to the rest of Davidson County.

The cars that do come downtown will be managed more tightly. NDOT references an expanded permitting system that will govern loading zones used by commercial vehicles and pickup-dropoff areas used by taxis and rideshare apps. Airports, including BNA, use a similar strategy to manage taxis, Ubers and Lyfts. Connect Downtown also references an additional fee charged to rides that begin or end downtown during peak hours.

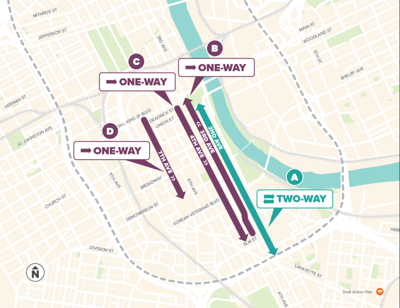

Updated traffic signals and patterns, managed by the city’s first Traffic Management Center, will marshal vehicles through downtown’s dense street grid. Second Avenue, a key connector, will be converted to two-way traffic, while Third, Fourth and Seventh avenues will become dedicated one-way streets.

A few themes emerge based on how the city is thinking about downtown in its latest 70-page report. First, downtown has officially become a residential umbrella — like Bellevue or East Nashville, populous enough to have its own neighborhoods, like a real city. Connect Downtown claims the downtown population has grown an eye-popping 365 percent between 2013 and 2023. This statistically strong trend marks a definitive shift from the urban core’s days primarily as a workday destination for commuters, a time as recent as the early 2000s.

Second, Nashvillians across the city frequently need to get to or through downtown. Right now, those goals are colliding, creating a free-for-all such that both car and bus trips downtown are “wildly unpredictable,” to quote the report. Third, people look to their personal vehicles to fill transportation needs — despite complaining about traffic and saying they want viable other options, like biking, walking or public transportation. The result is constantly clogged streets and confusing, inconsistent navigation inside the interstate loop.

The plan is still technically a draft, and NDOT invites comments via an online survey. The plan does not include a vision for mass transit, like the failed 2018 Let’s Move Nashville referendum, or any reference to rail travel. Recently elected Mayor Freddie O’Connell has spoken numerous times about exploring potential hookups to the limited railway infrastructure in the region, and recent upgrades at BNA include a possible light rail terminal.