There's a basketball game on every TV along the perimeter of Silverado Rivergate Night Club (more truthfully, large sports bar) on March 18. It's the first day of the NCAA tournament. Tennessee is playing San Diego State, a game that will come down to the final seconds of the second half and a 62-59 win for the Volunteers.

So the fact that not one person seems to be paying attention to basketball is — well, frankly refreshing. But it's also a bit disconcerting — completely out of the ordinary, you might say. From first rounds to last call, all night long, everybody in this brimming room is watching the center ring.

All that and it's not even an actual cage fight — as in, with an actual cage.

This sort of scene might help explain how mixed martial arts, or MMA, got to be so big so quickly around here. Still little-known to a large swath of the populace, MMA combines the grappling moves of wrestling with the lightning strikes and body blows of various martial-arts disciplines. Picture Bruce Lee's shape-shifting appropriation of various forms, including judo and karate — then imagine two Lees competing on the floor as well as on their feet.

MMA fights were, of course, illegal in Tennessee just two years ago, until lobbying pressure from promoters convinced the state legislature to put 2008-2009 budget talks on hold and get something real accomplished. Before MMA was legalized, fight teams wishing to compete had to go out of state — or fight in a parking lot, or maybe a basement, or maybe the back room of a brothel in a basement underneath a parking lot.

This weekend, on the other hand, there's one scheduled at a middle school in Winchester. And on April 17, less than two years after legalization, Nashville will host Strikeforce, an MMA fight night to be aired on CBS' Saturday Night Fights. It will actually be the second nationally televised MMA event in Nashville, a town where major-league baseball couldn't even steal a base.

For more than 20 years, Strikeforce was a kickboxing promotions company. Since 2006, though, it has been competing for MMA market share with its bigger, older rival, the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). The latter brought Nashville its first major MMA event, Fight Night 18, last year at what was then called Sommet Center. It drew more than 10,000 fans, an attendance record for the UFC. There was talk UFC would schedule a Nashville match to compete directly with the upstart Strikeforce, but it didn't materialize.

That leaves Strikeforce standing tall next week, with four local fighters on the card. Though there's no guarantee that any of them will make it to broadcast, they include Dustin West (vs. Andrew Uhrich) and Josh Shockman (vs. Cale Yarbrough) from the Nashville Mixed Martial Arts club. One hotly anticipated match is a face-off between two well-regarded locals: NMMA's Dustin Ortiz against Justin Pennington, who represents the Integrated Martial Arts Team — a fight that pits Nashville's most ambitious MMA operation against an underdog outfit on the Lebanon town square.

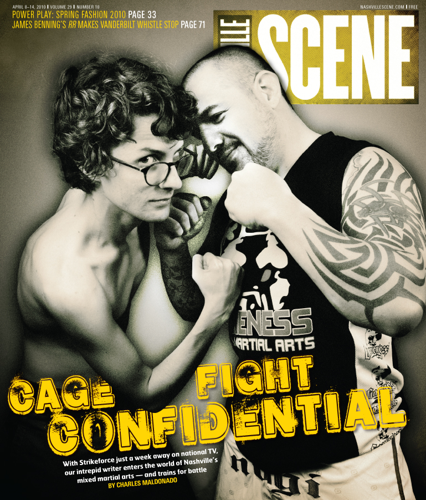

By contrast, tonight's Silverado deal isn't a particularly great event for the city's biggest MMA promoter, Ed Clay, whose family enterprises include Nashville Mixed Martial Arts as well as the Gameness Promotional Group and Gameness Fighting Team. It's been a while since he's done a fight night here, and it's not coming off seamlessly. The fights begin late, and throughout the night fighters are rarely where they need to be when they need to be there. The announcer keeps running out of pre-fight patter.

But Clay's mother, Regina Clay, the owner of Gameness Promotional, is coordinating things, and given the mild chaos, she's doing it gracefully. She jogs from the backstage area to her seat near the ring, rolling her arms over her head at the announcer. It's a signal that translates as, "Stretch it out, thank the bar again, thank the crowd, talk about basketball, mention our sponsors — especially Free At Last Bail Bonds."

With the exception of the main event between Nashville's Eugene Parris and Indiana's Eli Donker (which Donker will win by submission in round two), the bout card is still being thrown together even as some of the fighters warm up behind the curtain. At least two of the six fights will slog through three three-minute rounds before limping to a judges' decision.

"I'm sorry about that," Regina Clay will say the next day. "That really was not one of the better events we've done. Not bad, but far from our best."

Maybe so, but nobody at Silverado notices. There is the constant screeching of fighters' girlfriends. The college guys who are way too psyched about hearing "Enter Sandman" or "Down with the Sickness" over the speakers. The drunk asshole who yells "Titty power!" any time an overweight fighter reaches the ring. The crowd noise steadily amps up in volume and enthusiastic rage.

That level of local support is due in large part (or perhaps exclusively) to the efforts of local cage-fighting mogul Clay, Gameness/NMMA's head trainer, owner and figurehead. Or so says Ed Clay, whose every declaration of personal triumph is followed by something like, "I know how that sounds, but it's true."

"We got the legislation through," says Clay, who asserts that the burgeoning Gameness empire probably accounts for the bulk of the sport's local popularity — an assertion that, not surprisingly, doesn't sit well with some other Nashville teams. "We were the first ones to hire a lobbyist. We made the push. No one else made the push."

But legality alone doesn't account for MMA's quick rise in a city that's notoriously fickle about pro sports. If anything, it would seem to be a hard sell — an off-putting collision of smash-mouth brutality and unsettling intimacy. As I wrote after attending my first cage match in February, in the bowels of the State Fairgrounds:

"It was weird watching something so incredibly, kind of shockingly, bloody, that was at the same time so silly-looking. These fighters, on the one hand, really seem to be hurting each other in such a way that makes an uninitiated spectator cringe, but on the other hand, they are doing it in these bizarrely convoluted positions.

"Plus they're not really in shape, so they kind of look like be-shorted troll dolls playing superman with each other. And as has been noted elsewhere, the more brutal a fight becomes, the more it looks like tender lovemaking."

Watching that match, I wondered why MMA here had so quickly overtaken boxing, which I thought was more of a normal-people sport. Initially, I thought it was maybe a nutty reactionary thing. Boxing is perceived as corrupt, predictable, elitist and way too expensive. So maybe MMA is part of a populist regular-Joe backlash — boxing's tea party. Plus look at the fighters. It's a lot whiter than boxing, which also reminded me of a tea party rally.

But that's just theory — looking through a fogged gym window at best. To understand why people were so into MMA, fighters as well as fans, I decided I'd have to serve up my own neck for a stranglehold. I'd have to taste my own sweat and blood, with maybe a chaser of someone else's. I'd have to dip a toe in the training routine that turns fists into hammers and flesh into pulp, then see how it feels to crush or be crushed.

First, though, I'd have to hit the gym. And hope it didn't hit back too hard.

Training Diary 1

Scene: The headquarters of Gameness Nashville near the Nashville Zoo. ME sits writing in the gym when DEFENSIVE GUY walks up."So, do you want to be punched and kicked by a group of ex-Marines?" asks Ray Casias, a trainer at Nashville Mixed Martial Arts Academy, after my initial tour of the Gameness Training Center. "Or would you rather just lie supine on the mat there and wrap your legs and arms — angrily, lovingly — around the tree-trunk torsos of another group of ex-Marines?"DEFENSIVE GUY: What are you doing?

ME: Taking notes.

DG: You're from the Scene, right?

ME: Yep.

DG: Can I see your notes?

(Journalistic aside: No, you can't.)

ME: Why?

DG: Oh, uh, nothing. I was just trying to make some friendly conversation. I guess I'll just go fuck myself.

Those are not his exact words, of course. What he's actually asking is whether I'd like to start my training in the Thai Kickboxing or Brazilian jiu-jitsu program. I'd recently been to my first cage-fighting match, the Gameness Fighting Championship held in February at the fairgrounds. Signing up with the gym, my goal was to take full-on mixed martial arts lessons, which would combine stand-up kickboxing and on-the-ground BJJ grappling. That, Casias tells me, is an invitation-only program for trainees in whom the Nashville MMA staff can see some potential to join their fight team. So no.

Over two days, I've had my tour of the gym: 20,000 square feet of former warehouse space in an industrial stretch of Allied Drive off Nolensville Road. I've seen the Gameness octagon — the combat arena used in the February match I saw at the fairgrounds — as well as its smaller practice cage. Casias has shown me the facility's new prototype training gizmo — three punching bags and an army-green dummy strung up to a mechanical horsewalker. I've also had my brief private lesson: a few minutes of punching a bag and practicing basic grappling defensive moves with one Dave "Possum" Hurst.

I've signed my run-of-the-mill-but-ominous-in-this-context waiver relieving me of any legal recourse should I die in training, even as a result of staff incompetence. And I've seen both the kickboxing and BJJ classes on the mats. I've seen how many of the people here bear a body-mass resemblance to the hulking Casias, who has more than a decade of training in both disciplines and a horde of championship belts to his name.

Now, it's time to choose.

What you're looking at, I now think, is this: You can get kicked in the face by our guys, or you can get very close and personal with them on the floor. With option one, you might run the risk of a fat lip, a bloodied nose, a broken rib or two. With option two, you might also get hurt, plus there's the added bonus of having to overcome your most deep-seated social hang-ups. You know — the sensible ones that make it nearly impossible to go around leg-hugging total strangers.

Then there's the paranoia that makes you wonder — what with all the touching and rubbing — just how badly this crowd will kick the shit out of you if you accidentally make somebody think you're sexually aroused. But hey, 30-day free trial.

"Do you want to do kickboxing or Brazilian jiu-jitsu?" Casias asks.

"I guess I'll do jiu-jitsu?"

"I'll have to go to Pakistan, I guess," says Ed Clay to his mother. He examines a pile of Gameness Fightwear gis, some of which were apparently botched by the company's manufacturer in Pakistan.

He holds up two of the gis, garments traditionally worn in martial arts. One gi is torn and one is not torn. He tries to explain why, then he tries to explain the explanation, then he realizes that this is all pretty arcane stuff to an outsider. He just says the one that's not torn — his design — is "the lightest gi in the world." The torn one, for some reason he just tried to explain, is something else — something that apparently tears easily.

That settled, both Clays return to their respective work stations in the MMA's office, a large room at the front of the gym decorated only with the clutter of prototype gis and Gameness' promotional fliers. Here, not 100 feet away from where Ed trains the gym's MMA fight team, it's striking how un-mixed martial arts these people are — both small-framed and blond, the 28-year-old Ed still markedly baby-faced. Ed, as always, is at once annoyed (that the fabric is wrong) and amused (as if he knew they were going to screw up anyway). Regina just seems very busy.

When asked if they're excited about having three of their fighters on a major event card like Strikeforce, Ed and Regina Clay essentially give the same answer: "Yes, but ..." It's just worded differently.

"It's a step in the right direction, but it's just a step," Regina says. It's a circumspect and diplomatic response. And it's clear that the person saying it is a little shocked that she's ended up a fight promoter, after a career as an Army nurse followed by 18 years working for American Airlines.

She and her husband Tim came on full time in 2002, three years after her son had started the fightwear line. "Our friends get a kick out of it when Tim tells them what I'm doing — this little old lady as a fight promoter," Regina says. Given her medical background, it took her a few years to come around to the sport, especially in its first incarnation.

"When the UFC first started out, when it was really no-holds barred, there was no way it was ever going to go mainstream," she says. It wasn't until later, when the sport gave in to regulation by state athletic commissions and MMA events became slowly legalized across the country, that she decided it was worth a full-time commitment.

Ed, on the other hand, sounds like a man who was born for this business — someone who ends half his sentences with the prepositional phrase "in the world." Talk to him long enough, and you get an entire self-made-man spiel: political ambitions toward the state legislature, maybe an eventual gubernatorial run on a platform of state sovereignty. First, though, he's gotta get Gameness its rightful spot on the national MMA map.

"We have one the biggest gyms in the state, probably one of the biggest in the Southeast, probably one of the biggest in the country," Ed enthuses. "And actually, there were probably a lot of guys here who should have been on that card, but weren't because they train here" — meaning the promoters didn't want his gym to be overrepresented, he says.

"It's kind of like the difference between socialism and capitalism," he explains, "and I respect both. But I wasn't very happy about this."

Clay's ambitions are perhaps goaded along by lost time and past trouble — namely a 2002 conviction he and his brother received for dealing ecstasy. It led to a short prison stint and eight years probation. You get the impression that he needs everything to go faster so he can catch up to his 10-year plan.

But his words are a typical Ed Clay answer, in that his personal politics make a surprise appearance in a conversation where you wouldn't expect them. And because he immediately goes on to say that he couldn't give a shit.

"This Strikeforce thing is sort of a big deal for us, but it's less of a big deal for us than it is for other people," he says. "I work in goals, and five years ago, my goal was to build the best fight team in the world. I said I don't care how much it costs" — about $7,000-$8,000 per month in basic travel and food expenses, says Regina Clay — "I'm going to build the best team in the world. And right now, on our team, we have two of the best fighters in the country, Dave Herman [who's not on the Strikeforce card] and Josh Shockman [who is]. So, our guys are really going for bigger things. ...

"From a business standpoint, it would have been better for them if they had put more of our guys on. Our guys would push a lot of ticket sales." At this point, it's worth checking out the talent that's going to represent Gameness, Nashville and Ed Clay in the cage.

Training Diary 2

The first 15 minutes of each class are warm-up exercises. First jogging, then shrimping — a key escape technique that basically looks like you're manning an imaginary rowing machine — then somersaults, and finally a series of stretches. This is very refreshing and very pleasant. It's also very different from the 45 minutes of pungent choking and flipping that immediately follows.

Today's lesson is breaking your opponent out of a turtle position, flipping him back, and getting him into a chokehold. Should you end up on the receiving end, your only recourse is to cry uncle — the dreaded yet immediately gratifying "tap out." Instructor Shawn Hammonds, a veteran black belt and, of course, former Marine, takes mercy on me when it comes to assigning partners. Or so I think.

"Hey David, you go with that guy," Hammonds says, pointing at me. "He's never done any training at all before."

David is David Dunn, a soft-spoken 31-year-old Ph.D. student in theological studies at Vanderbilt. Though muscular, he's the only one here who's even close to my size. Plus he's brought his newborn baby with him, which means three things: (1) He's got a major responsibility, so he probably doesn't have some Fight Club death wish. (2) He's accustomed to thinking of other people as being highly fragile. (3) Since the baby coos in a car seat directly next to our part of the mat, rolling and flipping will be kept to a minimum. I'm immediately ready to claim Dunn as my best cage-fighting friend and forever partner.

Later, though, I find out that apart from his busy school schedule and the baby he's brought with him, Dunn's got two other kids who've been fighting strep throat for a few weeks. Hell hath no fury like a sleep-deprived dad. Too late it dawns on me that classes are a weekly catharsis for this very busy man, and controlled violence is more affordable than therapy. Theologian, hell. The fact that he's not going to take it easy on me is a major betrayal, and I now reconsider the whole best-cage-fighting-friend proposal.

By the third time, I'm getting thrown around the mat, which I'll only remember as a bunch of quick, nauseous head rushes. Still, after the first time, Dunn redeems himself somewhat by giving me my first and only compliment in this arena.

"I don't mean any offense by this," Dunn says, a bit red-faced and spitting on the ground, "but your bony arms are a huge advantage for you when you put someone in a choke."

Meeting NMMA's three Strikeforce fighters one after the other kind of feels like seeing a fighter's full career in three distinct stages. Josh Shockman, who runs Nemesis MMA in Murfreesboro, represents stage three: near-jadedness. He's fought in the UFC and has an 11-2 pro record. This may be why he comes off uninterested in the upcoming event. For him, Strikeforce is at best a lateral step.

Dustin Ortiz represents the other end of the spectrum. A 21-year-old ex-construction worker and former Franklin High School wrestling star, he just had his first pro bout at Gameness Fighting Championship VI in February. He won in the first round. Strikeforce, where he's scheduled to fight Pennington, will be his second pro match. He says he's not at all intimidated by the size of the event.

"I love putting on shows," he says. "I love people watching me, and I love them getting excited about watching what I'm doing." Ortiz came to the gym about two years ago to take jiu-jitsu class and was soon noticed by the trainers.

"I liked it more than working, so I decided to do it full time," he says.

Last year, he was invited to join the MMA class and began training full time with a $1,000-per-month stipend from Clay.

"I pay Dustin so he can train rather than have to worry about working," Clay says. "I don't pay a whole lot of other guys, but they know they're set. If I have someone who I think has the potential to get to a world-class level, I'll make sure he doesn't have to work, because this won't work otherwise." He points to contenders such as Cory Robison, one of eight Americans ever to win a world championship in Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

"We have six Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belts here, which is unheard of," Clay says. "They're all going to stay."

When a fighter gets to a certain level, and he can't afford to simultaneously stay on the team and pay rent, Clay offers many of them room and board at his nearby 5,000-square-foot home. Technically, it's a $500,000 "mansion" in a (seriously) "gated community." Actually, it has Clay plus seven twenty-something pro fighters living in it — giving the joint and its slept-in corners a kind of dorm-room-meets-refugee-camp look. The refrigerator is all Styrofoam and condiments.

"Yeah, if I want a relationship, I'm going to have to move out of that house, get a condo or something," Clay says.

Ortiz lives with his father, but he says the pay-for-training program helps him get by.

"Not having a wife and not having kids makes it easy for me right now." he says. "I feel right now, being 21, I'm young. I'm in my prime. I feel like waiting to go pro until I was 27 or 28, it would be too late."

Tell that to Dustin West, who is 30 and has a 2-2 record, having turned pro last July. He was in the Marines for six years and served in Fallujah in 2004, though he doesn't seem keen to talk about it. He does say that's where he started grappling.

"When I came back, I was working for this moving company, and I wanted to get back into fighting," West says. "So I sold all my stuff and moved to Vegas."

West, who now lives rent-free in a duplex owned by the Clays, says that the money is slim for someone just getting started. "It is not good," he says. "First year or so, you'd probably make more money working at McDonald's." After dislocating his elbow in the middle of a fight in Atlanta last year, West almost had to give it up.

Instead, he fought two more fights in excruciating pain. Why? A post-traumatic need for combat intensity? Thrill-junkie jonesing? A test of macho endurance? West's reason was a lot less exotic.

"I needed the money," he says.

Compared to Ed Clay's no-frills gladiator factory, everything about the Integrated Martial Arts Academy in Lebanon is quaint and adorable. Unlike the Clays' gym, there's nothing sprawling about this building. It consists of a small well-lit front room for mat work and a larger, dark, maybe unfinished back room with mats and weights. It's behind a Mayberry-esque storefront just off the Lebanon town square, on the same block as Grandma's Quilting and Sewing.

Where Clay sees only how few of his NMMA fighters made the Strikeforce card, IMA owner Brian Fussell glows with unambiguous joy about his team's fighter, Justin Pennington, going up against NMMA's Dustin Ortiz. It'll be Pennington's first fight as a pro.

"In the grand scheme of things, we're probably the smallest gym in this whole environment, but we've got a good base of fighters," Fussell says. "People have started to notice us. So when we heard Strikeforce was coming, a couple people showed up, and said, 'Hey, who would you like to have on the card?' "

Fussell suggested two fighters, including Pennington. But it seems Strikeforce had already been to NMMA.

"They knew Dustin Ortiz was going to fight, and they were looking for a really competitive fight in that 125 weight class," Fussell says. "Both of those guys were at the very top for the Middle Tennessee area. Everybody's been wanting to see this fight for a while. We know each other. We train together, but this fight is inevitable."

Ortiz, who specializes in grappling, has won a pro fight already. So he's favored over Pennington, who's known primarily as a kickboxer. But that, of course, doesn't mean much in this room, especially when it's going to print. Pennington, for his part, keeps his comments brief and to the point — mostly call-outs to his opponent.

"They couldn't have picked a better fight for my pro debut," Pennington says. "We've kind of called each other out in the past. This is his shot to do what he says he's going to do to me."

Training Diary 3

Sore. Unbelievably sore. Sore like I've never been. All the time. In the days that follow my first class, I've tried to go back to the gym twice, only to get within a half-mile and remember that I can go back home and eat cereal instead.

When I eventually make it back again for more classes, I find out two things. The first is that Chris Camacho, a fighter on the NMMA team and a former football player at UT-Chattanooga, will actually point and laugh at you when your pained gurgling draws his attention to your "I'm in severe distress" face.

In my case, given the situation, it seems like a perfectly reasonable face to be making. My fellow student Steve Dressler is a very good partner for a beginner, especially one like me with the build of a Buddy Holly action figure. But he's easily 24 times bigger than me, which he (very occasionally) forgets.

At the moment, he's administering a full-body squeeze that — I must say purely for legal reasons — does not feel at all like it is starting to sort of kill me. Tap out.

"I'm sorry, man, but that was hilarious," Camacho says, imitating the expression for me. Luckily, I can't really make it out through the floating pink TV-snow blobs clouding my vision.

That happens again — in a subsequent lesson when Dressler first chokes me on the ground, then walks counterclockwise around the choke, using his shoulder and the movement to create a tightening wrench effect around my neck. I see a tunnel and white light. Tap out.

"Choke days are the worst," says Dressler, helping me up from that mess. There are non-choke days?

The second thing I find out is that I'm starting to understand how this training works.

NMMA favors a hands-off immersion technique. The instructor shows us a move a few times, then sends us off to practice it, leaving each pair more or less alone to clunk through it.

Once we've practiced a move enough so that the instructor thinks each class member has, at the very least, managed a close approximation, we move on to the next move — a sequential advancement from wherever the last move left us. Over the course of several weeks, you'll thus have gone through an entire "bout" very gradually. Theoretically, this technique forces you to teach yourself the underlying logic of a move — the why as well as the how — and puts it into useful context.

The surprising thing to me is that this actually works. By my fourth and fifth lessons, I've got the basics — keep your chin down, keep your legs hooked in — not only in my head but in my muscle memory.

I have to admit that I understand MMA as a spectator sport better. I can identify some moves in a fight now — which means I can understand why the fighter's doing them, which means I actually understand, rather than just mindlessly acknowledge, that it's a real sport, a finely honed skill ... or rather, a whole group of skills slowly developed over a long time.

And since I'm able to watch it that way a bit more, I'm a bit less grossed out by the blood and the moments where I think somebody's neck is about to snap. But it's only been a couple of weeks, so just a bit. Maybe enough to give it another shot.

As a spectator.

Because really now, getting up this morning and not having my girlfriend ask me if I'm cage-fighting today was nice. It was even nicer when we didn't have to have the second part of that conversation — the part where I would say, "Yes," and she would say, "That is so stupid."

That I won't miss. Nor will I miss the reek of close-quarters combat — the various smells that may or may not be me, but I can't really tell because first the other guy will have to stop rear-choking me long enough for each of us to distinguish his own odor, which he will likely see as a waste of gym time. Also, I won't miss the rear-choking. I prefer not to explain more.

I'm done with this, and I think that's good. I am tempted to wrap my training experience up wistfully — to explain my newfound sense of lion-in-the jungle pride, to wax macho-poetic about my initiation into this band of brothers. But the truth is, I still can't raise my arms up all the way.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.